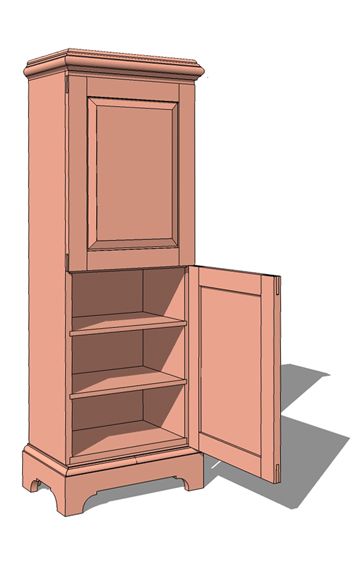

My SketchUp plan of the cabinet I plan to build for my next project.

I’ve been noodling my next woodworking project for several days now. It’s a fairly straightforward cabinet designed to hold different papers that my wife and I use to print cards and such. It will stand about 4 ft. high, with two frame-and-panel doors covering half a dozen shelves. It’s meant to replace a rickety tower of plastic trays in one corner of our study. In that room, existing doors and molding around the fireplace most likely date to 1750, when our house was built, and was almost surely planed by the original homeowner himself. It appears to be pine, stained a dark brown.

My aim is to make the new cabinet look at home next to the antique molding. So I designed the crown molding to complement the curves of the fireplace surround. Bridle joints on the new door frames will mimic the same type of joint on an existing old door. I’ll even finish the bevels on the cabinet doors with a handplane so that they don’t look completely machine-made.

Rather than cut the moldings at the router table, I plan to shape them with a Stanley No. 55 molding plane. This triumph of Victorian engineering (overly ornate and as wacky as the Mad Hatter) can theoretically duplicate any molding profile. In practice, the No. 55 has a well-deserved reputation for being mulish, finicky, cantankerous, and several other epithets that the children shouldn’t hear. I’ve managed to use my No. 55 to run enough moldings for a few picture frames. But for every foot of usable molding, I probably have two feet of chewed-up scrap.

The best article on the No. 55 that I’ve ever seen appeared in the January/February 1983 issue of FWW. It gave me confidence to try to conquer the plane’s mulishness, even though it still seems to be winning.

But ever the optimist, I plan to spend time next week running the 3 ft. of crown on my old handplane. I’ve ordered up enough wood so I can make plenty of scrap. To prepare, I’ve sharpened the cutters I need and cleaned the plane thoroughly. So I won’t have much of an excuse if I wind up with nothing but scrap.

Comments

The 55 is a bit older than I am, I think they arrived on the scene in the 1920's. If memory serves me right, it was supposed to be Stanley's "All in one" answer to the shelves, and shelves, and shelves of molding planes that woodworkers owned and used. In that respect, it shouldn't be too difficult to actually use, although adjusting it may require an advanced degree from an engineering college.

I'll just stick to my routers, thank you very much, and let you have the last laugh when my power goes out.

Gregory Paolini

I plan to use a router to cut the dadoes for the shelves. I'm not totally crazy. I think the real difficulty with the #55 comes when lunatics like me try to cut a quarter-round or ogee profile. You begin the cut with the smallest part of the profile, which makes the plane pretty wobbly against the work. If you can manage to get the cut started, things get easier as you work deeper into the cut and there's more wood supporting the cutter. It's relatively easy to use the #55 as a rabbet or filister plane; the square cutters work like those on any other handplane. Even then, the most finicky part of the plane is setting the depth of cut. The #55 doesn't have a standard sole; instead, it's designed with a series of skates and it's time-consuming to try to tweak the cutter for a good thin shaving instead of big fat chips. It doesn't take an advanced degree to set up the plane, just patience. It must have a dozen thumbscrews to hold fence rails, skates, cutters, depth stops and the like.

Best,

dh

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in