Alec Jordan, a 25-year-old woodworker from Bethel, Conn., recently uploaded images of his spalted maple and black walnut coffee table to The Gallery. Alec works with locally recovered wood and mills it in his backyard. Reclaimed wood is growing in popularity with woodworkers, so I decided to talk to him and find out more about his practice and how he works “green.”

Q: Are you a self-taught woodworker or do you have formal training?

A: I grew up working on my house with my father. After attending Sarah Lawrence College, where I studied sculpture and chemistry, I pursued a career as a sculptor. Since then I have incorporated my personal desire to build everything I need with the artistic vision I gained through my work as a sculptor. I seek to understand the scientific properties of the woods I “treecycle,” and believe it or not, much of my technical knowledge of woodworking comes from reading Fine Woodworking! I am also a welder of many years and I plan to incorporate some metalworking into my future designs.

Alec Sebastian’s “treecycled” coffee table

Q: You define “treecycling” as working with wood headed to the landfill or a chipper. Can you elaborate on this?

A: Most of my wood comes from a local land-clearing company. The owner is happy to give me any trees that he can’t sell to a sawmill. Sawmills pretty much only take perfect logs, so that leaves plenty for me. The oddball logs can be more interesting anyway, with curves or crotches that will have incredible figure. To me, it is the ultimate in sustainable harvesting. Of course, I wish the trees didn’t come down at all, but as long as they do, I can’t think of a better use.

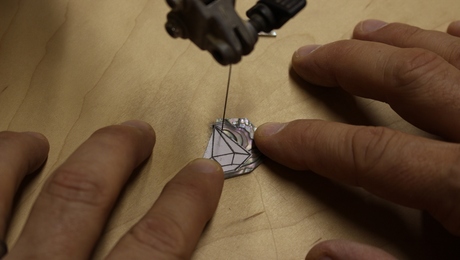

I mill everything with a chainsaw mill. Though backbreaking, the surface finish is quite good compared to any other kind of mill, and the whole setup is super portable. I can go to the log if it’s located in the middle of someone’s forest, as I did last summer in Wilton Conn., when a friend of mine let me mill a 25-in.-dia. 20-ft.-long dead ash.

Q: How did you find the wood for this coffee table?

A: I milled the top from a very large and old maple tree that I had to take down around seven years ago. It sat in my woods for four years where it spalted prior to milling. The walnut came from a tree that was cleared to make way for a new house in the area. I found it in the yard of a land clearing company.

Alec prefers lumber with defects, which add a lot of interest.

Q: Do you frequently work with spalted maple and walnut?

A: At the moment I certainly seem to be. I have a large cache of spalted maple that I cut a few years ago from a tree on my property, and it seems to be popular with my clients. As for the walnut, I am a big fan of using contrasting woods in my work, and as far as I am concerned, walnut contrasts beautifully with maple. Also, I just really enjoy walnut, its physical properties, its smell; it leaves me a little weak in the knees.

Q: How did you arrive at the design of the table?

A: The wood will often dictate the design. In this case the client knew that he wanted this ratty old piece of maple I had. I told him that the piece was more for show than functioning furniture, due to the degradation that was inevitable in a piece as wormy and spalted. He insisted, and with the help of some epoxy the top was born. The shape of the top is largely unchanged from the original rough-sawn piece. I merely bandsawed around the perimeter to clean up the edge. The base was a bit different. My design process usually remains in my head; I rarely sketch anything. I begin to go over every leg design I can remember. I think of classic designs that I can modernize, modern designs that I can make my own, then I usually come back to the function. I decided that I wanted to try a three-legged design for its self-leveling properties, for example it won’t rock on an uneven floor. I knew it needed to be fairly stable because it was going to be in a house with small children. And I knew that I didn’t want to distract from the top too much. I had been reading about multiple tenons and wedged tenons before I got the commission and thought, “why not use both?”. The curves were cut to achieve the ‘three legs’ as much as for their style.

Q: Which woodworkers do you admire? Where do you go for inspiration?

A: I admire any woodworker with the passion and guts to make a piece that challenges typical designs. When I look at someone’s work, I want to say to myself, “How the hell did he do that?” That said, George Nakashima is a clear inspiration, more for his challenge of traditional design than for his actual designs. In fact it was seeing pictures of his wood stash that inspired me to mill my own lumber. That way I am able to get completely unique pieces of wood that I know cannot be replicated. There are also a number of furniture makers working in Brooklyn N.Y., most notably Jonah Zuckerman of City Joinery, whose use of diverse woods and other materials, as well as his unique designs, really get my blood flowing. There are also a number of local woodworkers whose pieces can be seen in small galleries in western Connecticut. It pays for me just to keep my eyes open. Often my inspiration stems from a random form in nature that pops out at me and leads me to that table or completely unique design. I love exposed joinery and complex forms, but most importantly the woodworker must respect the wood, both from an aesthetic standpoint and engineering standpoint. I admire woodworkers who push the limits of joinery while preserving the integrity of the wood and I hope my pieces challenge what most people think is possible.

Comments

I like your feeling about trees. I noticed "chemistry" in your training. As a (retired) chemist myself, I appreciate that you are expressing your artful side. A chemist is by nature inquisitive and creative, and an understanding of the materials you work with enhances your art. Keep recycling that old wood.

I'm intrigued by what Alec said about the mill finish. He said, "I mill everything with a chainsaw mill. Though backbreaking, the surface finish is quite good compared to any other kind of mill,..."

I hadn't heard that of chainsaw mills. I would have thought that a bandsaw mill would leave a better finish (and waste less wood due to the narrower kerf).

Does a bandsaw mill really leave a good finish?

Swirt,

In my experience a chainsaw mill can leave quite a good rough-sawn finish, given a good sharp chain and one that has the appropriate angles ground into it. Bandsaws can leave a good finish too, though one has to control the feed rate carefully to keep the blade from undulating and creating a wavy surface.

The issue of surface finish out of the mill is important to me since I'm using sanders or handplanes to remove the mill marks. Most of the wood I use is too wide to fit in a planer.

The issue of the kerf is indeed one that I struggle with. A bandsaw would certainly waste the least wood. Both chainsaws and traditional circular mills have similar kerfs, somewhere in the order of a 1/4". It kills me to think that I could squeeze out an additional flitch or two per log if I milled using a bandsaw, but at this moment I can't justify the cost. Chainsaws are by far the cheapest way to mill.

Beautiful tables, I love the idea of using distressed or oddly-shaped pieces for tabletops. I'm wondering how you dry the wood after you've milled it? I was thinking about making a small kiln for myself but I don't know if it's worth it.

Cyclewvu,

I let all my wood air dry outdoors for at least a year. I use a good moisture meter that will tell me when things get to around 20%-15%. At this point, if I have a use for a piece I will bring it into the shop and put a fan on it. If it's winter time I'll bring it into the house and let it sit somewhere with both sides exposed.

I have often considered making a kiln of some kind. A solar or dehumidifier style kiln are probably the easiest to make. If you're drying very small quantities you can use your attic in the summer. Just remember to keep the wood covered with something semipermeable so it doesn't dry too fast.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in