See how I turn a board like these into flat, square workbench surface. It's for a dedicated sharpening bench that I'm working on. Read parts one, three, four, five, six, and seven for more details on this project.

Working off of my sketches and existing examples of trusted, work bench construction methods, I come up with a plan and begin adding up the numbers. This is generally how I approach a new design, from the sketch I mock up some shapes and sizes using off cuts and batons around my shop to see if in the ‘real world’ things still look like they do on paper. I settle on the overall size and start down my cut list taking into account the joinery.

The top work surface is where I begin and the two panels of 1″ thick, quarter-sawn white Oak are cross cut to length leaving about 1/4″ extra for love. The oak used is offcuts from a past project and has been in my shop for over 7 months now, so I know it’s extremely stable and will make a great work surface and apron. When I originally purchased the wood it was dimensioned before it left the mill so I can surface it all pretty quickly. From jointing plane to smoother I’ll get the top glued up before I even begin thinking about the apron.

Jointing the Edge

With the oak cross cut to length I’ll go ahead and joint it. To begin, I clearly mark the planks for grain direction and lay them on my bench top, reference faces up. I decide what two edges I’ll be jointing together. I mark the orientation of them with a builders triangle on the face surface and ‘fold’ them back together keeping the inside edges up. This book matched pair will be clamped together in my face vise and jointed simultaneously. I use a bevel-up jointing plane with a nice wide iron at 2 1/4″ and work the edges together. I’ll take a series of through shavings checking for square as I go. I finish off the process with a couple of stop shavings to insure no bumps along the edges. Again I check my work with a reliable straight edge and finally, a light pass again planing through, end to end. The nice thing about edge jointing two boards together like this is if you’re edges are slightly out of square it really doesn’t matter; because of the book matching we did when we clamped them, once unfolded any inconsistencies will cancel each other out. That said, while you’re planing, try your best to keep things square! (maybe this is one of those rare occasions you can get in some practice time while actually working on a project and not just something from the scrap wood pile?)

With the oak cross cut to length I’ll go ahead and joint it. To begin, I clearly mark the planks for grain direction and lay them on my bench top, reference faces up. I decide what two edges I’ll be jointing together. I mark the orientation of them with a builders triangle on the face surface and ‘fold’ them back together keeping the inside edges up. This book matched pair will be clamped together in my face vise and jointed simultaneously. I use a bevel-up jointing plane with a nice wide iron at 2 1/4″ and work the edges together. I’ll take a series of through shavings checking for square as I go. I finish off the process with a couple of stop shavings to insure no bumps along the edges. Again I check my work with a reliable straight edge and finally, a light pass again planing through, end to end. The nice thing about edge jointing two boards together like this is if you’re edges are slightly out of square it really doesn’t matter; because of the book matching we did when we clamped them, once unfolded any inconsistencies will cancel each other out. That said, while you’re planing, try your best to keep things square! (maybe this is one of those rare occasions you can get in some practice time while actually working on a project and not just something from the scrap wood pile?)

The Glue Dance

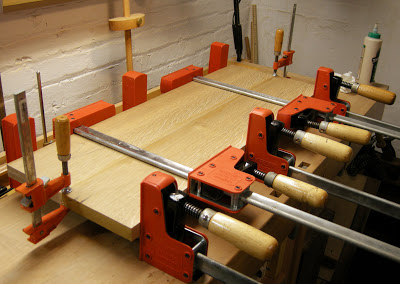

With the edges jointed I’ll glue up the panels and set them aside for the night. Here’s my method for gluing two panels together.

With the edges jointed I’ll glue up the panels and set them aside for the night. Here’s my method for gluing two panels together.

Because of the stopped shavings I took earlier, when gentle pressure is applied using only the middle clamp, I’m confident the outside edges of the joint will be tight.

So a generous amount of glue is spread and I begin again at the middle clamp bringing the pieces together. I use downward thumb pressure across the joint to keep the seam flat and won’t over tighten this first clamp yet- I’ll come back to it in a minute. With the middle of the stock held firmly together, I’ll use a couple of ‘F’ style clamps placed on the outside edges and draw the seam down flush along its length. Then working out from the center again I start tightening things up. I stagger the pressure as I go, from left to right and then left outside and finally the right outside clamp. With the five clamps secure I’ll move back across and re tighten them all down to finish. Take a step back and have a look- double check your grain is running in the proper direction and your building triangle is mated happily back together. This will be your last chance to change anything!

Go make a coffee and check your email, come back in an hour and begin cleaning up the glue. I’ll work between the clamps and remove any squeeze out after it has started to cure but before it’s too hard to easily scrap away. This is also when I’ll usually remove the two outside ‘F’ clamps; if I leave them on overnight I’ll have some deep bruises to deal with tomorrow.

“Top of the morning to ya!” The glue set up overnight so I remove the clamps and get ready to work. A card scraper down the seam removes any final bits of glue- I’m careful not to tear away any wood with it. I’m happy with the results- this oak is stable and sits well on my bench top-another good sign! I’ll double check with my winding sticks and a metal straight edge taking note of any high spots or twist across the surface.

A few light passes with the jointer followed with a smoothing plane and I’ll double check one edge for square. I now have a reference face and edge and can continue on with dimensioning the panel. I’ll use my panel gauge and scribe the finished width around the perimeter; because this was pre-dimensioned wood and I took my time with the glue-up, I’m happy to say the piece is almost square with just a few light passes along one end. With that, I now have a panel with two long edges, completely parallel and square with one finished face.

I’ll check the thickness throughout the panel to see if it needs any dressing and working from the bottom, I’ll plane the stock to final thickness. Not much to remove so this process is pretty straight forward. Four sided stock with two ends that still need to be addressed- that’s where I’ll go from here.

Planing End Grain

I get asked alot how I deal with the long end grain on panels. I think some woodworkers are intimidated when it comes to this area so I’ll show you the steps I use.

I get asked alot how I deal with the long end grain on panels. I think some woodworkers are intimidated when it comes to this area so I’ll show you the steps I use.

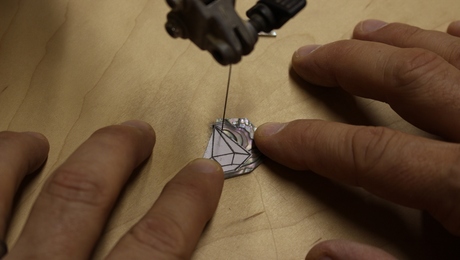

So first things first I’ll scribe a deep, crisp line around the perimeter with a knife working off a reliable framing square. The amount of wood I’m removing is very minimal, no more than 1/8″. Again, the time I took to carefully glue up the panel makes these later steps so much easier.

With my line scribed I’ll place the panel vertically in my face vise and block up the bottom off of the shop floor. From there I’ll clamp the left side of the panel in the vise and hold the right side with a surface clamp installed in one of the 3/4″ holes I have across my work bench apron. My bench didn’t come like this but it’s a feature I could never live without. Before I fully tighten the vise and clamp I like to place a small level across the top of the piece.

With my line scribed I’ll place the panel vertically in my face vise and block up the bottom off of the shop floor. From there I’ll clamp the left side of the panel in the vise and hold the right side with a surface clamp installed in one of the 3/4″ holes I have across my work bench apron. My bench didn’t come like this but it’s a feature I could never live without. Before I fully tighten the vise and clamp I like to place a small level across the top of the piece.

Also, because we’re dealing with end grain and I don’t want to blow out the face grain on the far edge of the panel,(spelching) I’ll clamp a piece of scrap wood, thicknessed the same as the work piece and tighten everything down to get started.

I’m using my bevel-up jointer again, set to take a fine shaving and carefully work my way down. I’m taking light passes, always watching for those first shiny edges starting to appear. It’s hard to put into words but you’ll know it when you get there. Being careful not to over-shoot, I work my way down so I can see my scribe line still wrapping the entire perimeter. With that tiny strip left glistening, I know the edge is square. (but I’ll still double check it!) Now I can safetly measure up off of this edge and follow the same procedure for the sixth and final side.

I’m using my bevel-up jointer again, set to take a fine shaving and carefully work my way down. I’m taking light passes, always watching for those first shiny edges starting to appear. It’s hard to put into words but you’ll know it when you get there. Being careful not to over-shoot, I work my way down so I can see my scribe line still wrapping the entire perimeter. With that tiny strip left glistening, I know the edge is square. (but I’ll still double check it!) Now I can safetly measure up off of this edge and follow the same procedure for the sixth and final side.

So there you have it- a work bench surface, square on all six sides. It may seem like a lot of steps but the above process probably didn’t take much longer than it just took me to write this post. I’m ready to begin the bread board ends and assemble my pieces for the apron. That will be next time.

Cheers!

Comments

With this type of formal approach, wouldn't the work be more authentically done in the light of day, or else by glow of lantern? And the photos, taken, presumably, with a digital camera, by Daguerreotype?

I agree with dwmmd213. Aside from the fact that I love to use power tools, time is way too precious to build everything using hand tools. This would seem to me to be precisely the place where producing the bench more quickly with power tools would allow the woodworker to sharpen his planes and chisels and get on with building a project where the application of hand-tools skills really makes some sense.

dwmm213-

A daguerreotype- now your talking-that would be right up my alley!

Maybe I'll search through some antique stores and try to find one.

And as far as the light of day- I wish...it's pretty dark down in here my basement workshop.

and tablesawer- time is what you make of it and the journey in my world is the destination. I do this work using only hand tools because I enjoy the process and to me this is a project where 'the application of hand tools makes sense'.

maybe you two should hook up sometime and compare the size of your...'saw blades' ;)

cheers!

Tom builds stuff by hand because he likes to, and it's about time that more of these techniques are brought back to light. Thanks to Tom for posting his process.

In recent years it has become oddly Luddite to hang on to the notion that working with hand tools is something which belongs only to the past.

kennethw-

well said...and thanks for the support!

;)

cheers.

Tom....I was wondering what method you use to strengthen joints of table tops, etc, when working with larger peices. I see simply glued the edges together on this peice. I assume you are not using a plate jointer! : )

Tchapin-

When I build pieces that have large surfaces my method for joining panels is always the same and thats with a good, clean glue joint. I've never felt the need for adding mechanical fasteners or some other kind of method like buiscuits or dowels etc...must situations in my work that have glued panels usually incorporate some other joinery aspect-so even though a panel may only be glued, it's usually held by some other means as well. This top as an example is held from the bread board ends as well as the dowels into the front apron. Other case work may have a dovetailed carcass or a through tenon.

Modern glues are incredibly strong and for edge gluing boards seem to be quite adequate. I suppose in some rare occasion where extra strength would be needed some blind dowels could be used or even something decorative like a butterfly joint across the seam comes to mind.

Hope that answers your question.

thanks again.

Tom

I found your article very informative especially since I'm just getting into woodworking. I am fascinated by the workbench you used in this project. Do you have plans on how to build one? It has some features that I believe would like to incorporate into the bench I'm building.

Thank you

David

Another newbie question ...

It looks like these are an important part of the process, what are "a couple of stop shavings" please?

RD16- thanks for the question- The workbench I have is one I purchased a few years ago through Garrett Wade- they call it a traditional cabinetmakers bench. If you're interested in building a bench I'd suggest you pick up Chris Shwarzs' book on workbenches. It'll give you a ton of great information on the history of workbenches and a couple of good workbench designs.

and DuncanSuss- a 'stopped shaving' is done while you plane the edges of boards crating a slight concave edge over its length. You start an inch or so in from the front edge and stop just shy of the opposite end while planing. Make sure you're taking a light cut with your hand plane. After a few passes your plane will stop cutting and you're done! Essentially you're only planing the mid section of the plank creating a very slight hollow. This is a good thing. Once you glue and clamp the pieces together you'll have nice tight seams on the ends. Search through the archives here at Fine Woodworking.com for an article on edge jointing boards by hand and you should find some more information- thanks again for the question.

Cheers!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in