Spalted wood: Dissecting the Colored Molds

The big trick in utilizing molds for spalting is knowing which to use, which to avoid, and what safety precautions to take if you decide to use some of the more irritating varieties.

Surface green stain on maple. Some green stains can be irritating to work with.

Ah, molds. They make us sneeze, can give nasty infections in immunocompromised people, and are responsible for some of the most brilliant colors on wood. The big trick in utilizing molds for spalting is knowing which to use, which to avoid, and what safety precautions to take if you decide to use some of the more irritating varieties.

First, a review

In case you don’t remember, there are two fundamentally different types of fungi that spalt wood. Decay fungi actually decay the wood, causing it to become structurally less sound. Mold fungi do NOT decay wood, but may increase its permeability (meaning it takes 6 coats of finish to get a decent luster instead of 3). Decay fungi are of no major health concern, especially since everyone working with wood should be wearing a respirator and goggles anyway. Remember, wood dust is a nasty carcinogen. Some mold fungi irritate allergies, the same way a dog or cat might. Others are toxic in high quantities, and some are completely benign.

Surface versus penetrating colonization

Most mold fungi will not colonize into the wood, and will remain on the surface. I don’t generally consider these fungi to be spalting fungi, except in rare instances. Surface colonization molds are also some of the most toxic, likeAspergillus spp. Many of the green stains visible on the surface of wood are from Penicillium spp. and Trichoderma spp., and some species within all of the aforementioned groups are toxic, while others are perfectly fine.

Since it can be nearly impossible to tell them apart without a scope, use caution when spalting with these fungi. Spray (and by spray, I mean drench) the surface of your wood with 91% isopropyl alcohol and allow it to dry before turning. The alcohol will take care of most of the spores. If you aren’t concerned about keeping the color, repeat the above step with 10% bleach as well, for added protection.

Since surface molds are tricky to work with and potentially hazardous, I’ve never classified them as spalting fungi, because they do not spalt in the truest sense of the word. However, some molds colonize only the surface of wood, but secrete a pigment that penetrates deeper. These are the wonderful spalting molds, and deserve special attention.

Spalting surface molds – a rare breed

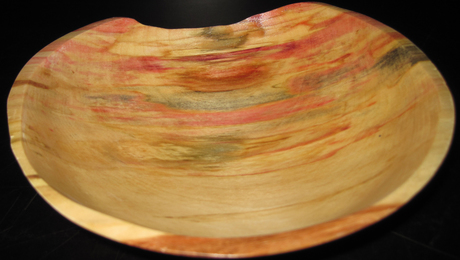

Certain molds, like Chlorociboria (blue-green stain) and Arthrographis cuboidea (pink stain) primarily colonize the surface of wood. Their pigments then diffuse down into the wood, creating beautiful spalting without any decay. Brilliant! And neither of these two fungi are known to cause health problems in healthy adults. However, that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t take precautions anyway. Who knows what you may end up being allergic to!

pink stain of Arthroghraphis cuboidea. be careful you don’t mistake it for Fusarium.

Penetrating molds – ye ole blue stain

Perhaps the most well-known penetrating molds are the blue stain fungi. The great majority of these are not harmful, but this is such a large grouping of fungi that I’m sure at least a couple of them must be irritating to someone somewhere (and not just irritating in the pocket book). Blue stains quickly penetrate wood, leaving behind anywhere from a light baby blue to a nearly black stain in their wake. They’re great fun to use, especially when paired with other brightly colored fungi.

ID tips

1) Green means stop

So the real trick now is to tell the surface molds from the penetrating molds, and to avoid most of the surface molds altogether. A good rule of thumb is never trust anything green. I’m not talking about the aquamarine green ofChlorociboria, but the forest green shown above. Every so often I get a green stain to take internally, but mostly they just surface colonize and make me sneeze. A good number of them are also toxic, so its best to just stay away unless you are armed with some alcohol and bleach.

2) Blue means go

Blue stains are mostly harmless, so have no qualms about anything blue. The same goes for the blue-green Chlorociboria stain.

3) Hesitate on pink

A bright pink color can be cause by the harmless Arthographis cuboidea, or by Fusarium species, some of which are quite harmful. Unless you know your spalting tubs are colonized by Arthrographis, be sure to spray down your wood before use.

Remember –

Fungal spores from molds can cause allergic reactions in sensitive individuals, in the same way that dust, pollen, and animal dander can affect others. Some fungal spores are dangerous to people with repressed immune systems, or can be dangerous to healthy adults with extended exposure. With that said, please keep in mind that wood dust is just as harmful, if not more, than some of the nastiest fungal spores. If you are wearing goggles and a respirator when you turn, and have an air filtration system in place (as you should even when working with unspalted wood), you don’t need to be concerned about the spores from spalted wood. Remember – spalted wood presents no additional danger over plain wood. Now, go forth and spalt!

Seri

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

DeWalt 735X Planer

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

Ridgid R4331 Planer

Comments

I may be a little sheltered when it comes to the various types of woodworking in that I have truly never heard of doing anything like this. However, it seems really interesting to me. So my question is, how do you get wood with the mold on it? Merely luck of what you find or do you grow the mold on the wood?

-StairPartPros.com

Spalted wood has been utilized for centuries for artistic work (like intarsia), and today is commonly used by turners. A lot of people have experimented on the conditions necessary to cause the spalt, instead of waiting for nature to do her thing. If you leave a log on the dirt long enough, it will spalt. The problem is, you have no control over what type of spalting you get.

If you do a search here on FWW for 'spalting', you should come up with other blog entries I've done about induced spalting. They offer insight into some of the responsible fungi, and methods for reliable home spalting.

To more directly answer your question - you can easily inoculate your wood with the mold color you want (or the wood decay you want, if you're after zone lines or bleaching). To do so you can either harvest the fungi yourself from the woods, or buy the active cultures online. The mold grows on the wood and you stop the process when you have achieved your desired color. Induced spalting is a heck of a lot faster and more accurate than just letting airborne spores have their way with your lumber!

Well it seems like quite a fun process. I think that the levels of uncertainty is what is appealing to me. Because even when adding the spores myself I can't be sure of what I'm going to get, right?

Thanks for all the info so far!

I'm a bit sheltered to. What are the applications for spalting. Antique replication? About how long does it take? Why wouldn't I just use dyes and stains to create the look I want? Thanks for the education!:)

Does spalting do more than just change the color?

StairpartPros - If you add the spores yourself, you can be sure that at the very least you will get that color. The iffy part is what other types of spalting you might get as well from airborne spores or spores that are already on the wood. You can take out 99% of the guess work though, if you first sterilize your wood before inoculation.

R Williams - Historically spalted wood was used for intarsia. Today it is commonly used as a decorative wood in turnings and for things like cabinet panels (any non-load bearing application). Objects made from spalted wood fetch a nice premium, similar to birds eye maple.

Spalting takes anywhere from a month to years, depending on the fungus you use and the type of wood you inoculate. Aspen spalts more quickly than birch, etc. In general, bleaching and blue stain take the least amount of time, whereas zone lines and other pigments take far more.

You could use dyes and stains, but I think part of the appeal of spalted wood is that it is a natural process. You may be able to pick what colors you want, but you have no control over where they go on the wood, how they interact, etc. It's natures paint, and that, for some, makes it highly intriguing.

Yes, spalting changes more than just the color of the wood. I was actually going to write about this in a future post, so here is the bare bones version. White rots (cause bleaching / zone lines) digest the wood. Strength properties are grossly affected and as such, white rotted wood should never be used for load bearing applications.

Most stains do not affect the strength of the wood, but most will affect the wood permeability. All this means is that more finish is required on stained wood.

Some types of spalting alter the surface of the wood enough that new types of spalting can easily colonize. Sometimes, pretreatment of wood with one type of fungus is needed before another one can grow.

Hey thanks Dr.! Very good info. I could think of many applications! One other question; who is typically in the market for spalted wood? how much more are they willing to pay for it, or better yet, how much more should I charge for works created using spalted wood? Also, please excuse my ignorance here, I don't know what intarsia is. I supose I could google it though.

As far as I know, most people who shop at art shows and fairs for wooden turnings seem to know what spalting is all about. Most woodturners are also in the know. I sell most of my finished spalted pieces to people who routinely go to galleries to select wood turnings, and most of my spalted wood sells to woodturners and wood puzzle makers.

For pricing, I charge based upon the type of spalting. Blue stain is so ridiculously easy to get going that I rarely even increase the price of the bowl. Pieces with excellent zone lines will get perhaps a $10-$15 markup, whereas pieces with a penetrating green stain may be marked nearly $100 more than a plain piece would be. So basically, I charge increasing amounts for increasing difficulty to work with, or increasing colonization time.

Intarsia is wood inlay, similar to marquetry. Wikipedia has an excellent article on intarsia, if you are interested.

Hope I helped!

I once bought a log run of hard maple that was beautifully spalted (by nature). The sawyer appolized to me for it; I smiled and loaded up the wood!

I find you can often get a discount on blue stained lumber at lumber yards, since there are still people who view it as a defect. If you're not interested in spalting your own lumber, its a great way to get spalted lumber for cheap!

It seems the most attractive feature in spalted wood is the contrast it provides. I get some rewarding coments when people see some of the things I've done with spalted birch. Here at least on the BC coast the process is easy. Cut down a birch tree, roll it into the shade and come back in a year to find it covered with fungi. The fungus sends dark streaks through the wood to contrats with the pale birch. I have the Alaska chain saw mill so cutting it into boards is easy, but it can be done free hand with any small saw for that matter. I leave it to dry in the shed for several months then cut it up on the band saw. Some of it is 'past the due date' and must be discarded but as it is not intended for structural I have plenty left for special boxes or cabinet doors etc. I find it marries well with smoked poplar which has a deep coffee colour. I scrounge that from left over flooring instalations.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in