Spalted Wood: Its not all about the fungus!

Spalting involves a wide range of fungi and is certainly not limited to white rot and zone lines.

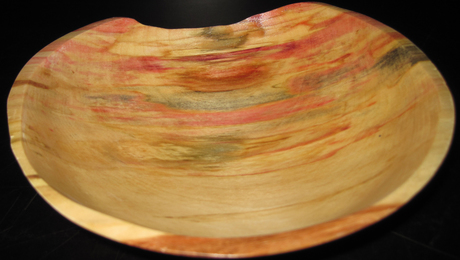

White rot, zone lines, and pink stain on birch

Internet consensus appears to be that the easiest woods to spalt are maple, birch, and beech. If you backtrack this statement far enough, it leads you to (what I believe to be) the original source – the Ohio DNR. If spalting were merely defined as the actions of white rot (bleaching) fungi, I might agree. However, as I’ve discussed before, spalting involves a wide range of fungi and is certainly not limited to white rot and zone lines. Colors add a lot to spalted wood, and fungal-based pigments are cool, no matter how you look at them.

pink stain on birch

Woods that spalt

There appears to be a very big difference between woods that spalt well in nature, and woods that spalt well in my bathroom. For instance, fresh cut basswood will turn solidly blue in two weeks if put into a plastic bag, but won’t do much of anything if accidentally dried and rewetted. Birch bleaches readily, and forms zone lines in time, but getting stain to penetrate can be a lengthy process. In nature, most birches would disintegrate before the pigment stage, so home spalting of birch has to be well regulated to allow pigment and control bleaching. Sugar maple appears to be universally good at all forms of spalting, but then, so too is aspen, which most people tend to overlook. Silver maple is another lover of blue stain, bleaches well, but rarely forms zone lines. Apple takes to white rot very easily, whereas pin cherry does very well with pink stain.

Woods that don’t spalt

Contrary to internet lore, beech is not great at spalting. The sapwood does well with zone lines and bleaching, but since beech is primarily heartwood, you’re not getting much bang for your buck (heartwood traditionally does not spalt well). Most conifers spalt well, unfortunately, brown rots are so destructive that you’re unlikely to have anything usable to work with. Tropical woods, such as teak, ipe, mahogany, and koa, are hard to spalt with North American fungi (although I’m sure fungi from their native countries could do a fine job). The exception to this rule is mango, which I have had great success with in terms of zone lines.

Why do we care?

Sure, you could go cut down your neighbor’s annoying pin cherry (it is half on your property, after all), toss it in a bin with a mushroom you picked off a sugar maple stump, and hope for the best. However, the whole idea behind controlled spalting is to have some control over the process. Your spalting will proceed much more quickly if you chose woods and fungi that grow well together, and don’t try to force combinations that are unlikely to occur in nature. If you want a low maintenance wood, choose sugar maple or aspen, which do not appear to have any fungi preference.

All it takes is a bit of planning, and you can cut incubation time in half and get far greater consistency in color than with chance / dumb luck alone.

Seri

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

DeWalt 735X Planer

Ridgid R4331 Planer

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in