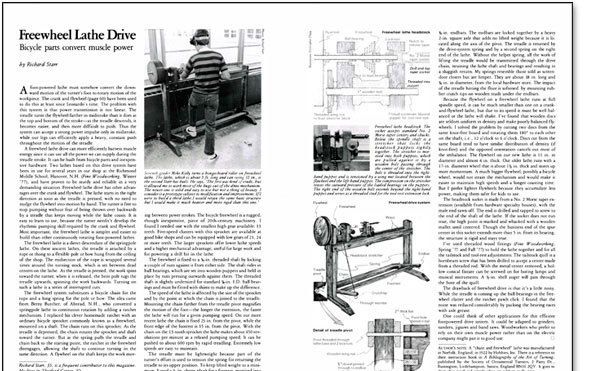

Synopsis: A foot-powered lathe must somehow convert the downward motion of the turner’s foot to rotary motion of the workpiece. The crank and flywheel have been used to do this at least since Leonardo’s time. The problem with this system is that power transmission is not linear. The treadle turns the flywheel farther in midstroke than it does at the top and bottom of the stroke—as the treadle descends, it become easier, and then more difficult to push. Thus the system can accept a strong power impulse only in midstroke, while our legs can efficiently apply a heavy, constant push throughout the motion of the treadle.

A foot-powered lathe must somehow convert the downward motion of the turner’s foot to rotary motion of the workpiece. The crank and flywheel (page 60) have been used to do this at least since Leonardo’s time. The problem with this system is that power transmission is not linear. The treadle turns the flywheel farther in midstroke than it does at the top and bottom of the stroke-as the treadle descends, it becomes easier, and then more difficult to push. Thus the system can accept a strong power impulse only in midstroke, while our legs can efficiently apply a heavy, constant push throughout the motion of the treadle.

A freewheel lathe drive can more efficiently harness muscle energy since it can use all the power we can supply during the treadle stroke. It can be built from bicycle parts and inexpensive hardware. Two lathes based on this drive system have been in use for several years in our shop at the Richmond Middle School, Hanover, N.H. (Fine Woodworking, Winter ‘ 77), and have proven to be sturdy and reliable in a very demanding situation. Freewheel lathe drive has other advantages over the crank and flywheel. The lathe starts in the right direction as soon as the treadle is pressed, with no need to nudge the flywheel into motion by hand. The turner is free to stop pumping without fear of being thrown over backwards by a treadle that keeps moving while the lathe coasts. It is easy to learn to use, because the turner needn’t develop the rhythmic pumping skill required by the crank and flywheel. Most important, the freewheel lathe is simpler and easier to build than other continuously rotating foot-powered lathes.

The freewheel lathe is a direct descendant of the springpole lathe. On these ancient lathes, the treadle is attached by a rope or thong to a flexible pole or bow hung from the ceiling of the shop. The midsection of the rope is wrapped several times around the turning stock, which is set between dead centers on the lathe. As the treadle is pressed, the work spins toward the turner; when it is released, the bent pole tugs the treadle upwards, spinning the work backwards. Turning on such a lathe is a series of interrupted cuts.

The freewheel system substitutes a bicycle chain for the rope and a long spring for the pole or bow. The idea came from Berny Butcher, of Alstead, N.H., who converted a springpole lathe to continuous rotation by adding a ratchet mechanism.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in