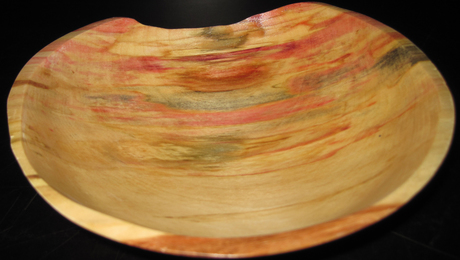

spalted birch with zone lines and white rot

I receive numerous e-mails every week from woodworkers interested in spalting outdoors. Whether this is because their spouses have banned spalting tubs in the bathroom or a lack of interest in spalting bin maintenance is unknown. What I do know is that spalting outdoors is a whole different game. You’ve got to deal with temperature fluctuations, droughts, waterlogging, winter, mold from falling leaves, etc, all of which significantly slow down the process. Certainly outdoor spalting works – spalting is just the beginning stage of Mother Nature’s fantastic recycling program. But you have far less control with outdoor spalting, especially when it comes to getting the type of spalting you want.

The e-mail

Not too long ago I received an e-mail detailing a failed outdoor spalting attempt. Failed outdoor spalting after previous success is more common than you might think, and often leads to a general confusion about just what is going on biologically. Mr. Scott was gracious enough to let me utilize his photos and e-mail information for this post. So lets explore the mysterious case of Second Year Spalt Failure.

The Background

Several years ago, Mr. Scott was given some freshly felled birch from his neighbor’s yard. The logs sat around not more than one to two days before Mr. Scott collected them and placed them in a little forested area on his property. The logs were ignored for two years, although after the first year he rotated the logs so the bottom side faced up. When the logs were cut at the end of the second year, this is what Mr. Scott ended up with:

and he considered the logs a success. Thrilled with the results, Mr. Scott went out and purchased several cords of birch from a mill yard (which had been sitting for several months), placed it in the exact same place on his property, waited two years, then cut into it. And this is what he found:

The logs are spalted, but not really in the way he had hoped. But why didn’t the logs spalt in the exact same way? Why did Mr. Scott get zone lines the first time, and blue stain the second time?

The Biology

Unfortunately, the answers aren’t as simple as I’m sure many would like. A whole host of factors came into play in the two sets of wood. The four most probable are the following:

1) Moisture content matters

In fact, moisture content of your wood is probably the most important part of the spalting process. Internal zone line formation needs at least 30%, and would like a lot more. Logs sitting outside, even with bark on, still dry out quickly. So the original logs used had a much higher moisture content than the purchased logs, which discouraged the zone lines.

2) Blue stain matters

Those pesky blue stain fungi! They may look great on a finished piece, but once they’re on wet wood you’re going to have a hard time getting other fungi to grow. Blue stain fungi go after wood right after it is felled and eat up all those easy sugars. They’re very prevalent in log yards since the rain keeps the logs wet enough for blue stain to establish. Even if blue isn’t visible, its a safe bet that if the logs have been sitting outside for more than a week that the fungus is already established. Other fungi are capable of growing on the wood once its been blued, it just takes a little longer, and zone lines tend not to form.

3) Leaves matter

In an attempt to get things a little wetter, Mr. Scott covered the purchased birch with leaves from the forest floor. Leaf litter is a great way to keep moisture in, unfortunately the molds that come with leaves aren’t really the type that spalt wood. Covering your logs minimizes the possibility that airborne white rot spores will land and colonize. Instead, you’ve given the leaf mold spores free range on your logs.

4) With birch, pre-colonization matters

Something that really complicated the whole matter was the choice in wood species. Birch has a tendency to be colonized by fungi that actually grow while the tree is alive (but under stressed conditions). If the neighbor’s tree was felled due to disease, then the necessary white rot fungi were already well established in the log. Birch trees felled and stacked by a mill would have been cut if healthy (for better value), hence they would not have already had fungi inside them. So the two different sets of logs came into Mr. Scott’s possession with very different fungi in them. The ones from the mill had to pick up fungi from the air to spalt – a process inhibited by the leaf litter. However the first batch of logs already had all the fungus it needed to start.

What To Do

So what is an outdoor spalter to do? The best option is to inoculate your wood with a known spalting fungus. That way you know that at least one decent fungus is in there, doing its job. You can do this by picking mushrooms from downed hardwoods in the forest and placing them on your logs (or even rubbing them on your logs like a fine baste for a turkey), or going the more expensive yet more reliable way and buying an active fungus culture to spread over your logs. Either way, adding fungi will give you a strong possibility of actually ending up with the spalting you want.

So best of luck to all of you with your outdoor spalting adventures. And many thanks to Mr. Scott for sharing his spalting story. May your days be full of cheer, and your outdoor spalting logs filled with zone lines this holiday season.

-Seri

http://www.northernspalting.com

Pssst! Spalted wood isn’t as dangerous as people think! Check out this post for all the reasons why!

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

DeWalt 735X Planer

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

Ridgid R4331 Planer

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in