In his article in Fine Woodworking #228, Garrett Hack marveled at the small stature of an ebony tree he encountered in Java some 30 years ago. “In a climate where trees grow year-round, this 90-year-old was about 11 in. in diameter.” That slow growth goes a long way towards explaining why the species is so dense, and why it carries such a hefty pricetag. Any woodworker feeling the urge to experiment with this king of the tropical hardwoods would do well to heed Hack’s tips on working it. It all starts with machining–or the lack thereof.

Go Lightly on Machines

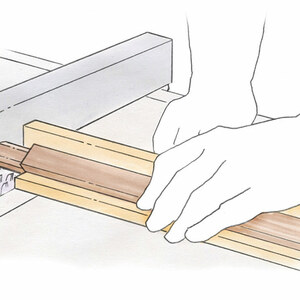

To avoid wasting any of the ebony, I tend to use the bandsaw, handsaws, and handplanes to cut pieces to size, rather than the tablesaw or jointer. I’ve never sent ebony through a planer for fear of it blowing up, quickly dulling my blades, or both. I will occasionally use the jointer to straighten an irregular edge. I’ve also turned ebony, with beautiful results, as the material is able to take the finest detail.

Hand-shaping the wood requires sharp tools and some finesse. When planing the long grain, fine tearout is common because of ebony’s hardness and interlocking grain. I’ve had success with both standard and high bevel angles. Just start with a super-shapr blade and expect to resharpen frequently. For best results, set the plane for a fine cut, with a tight throat. I clean up any fine tearout with a scraper.

When working end grain in these brittle woods, chipout is common, so I prefer to use a low-angle plane, taking a light cut with a tight throat and skewing the plane acutely.

To shape the material, I often use scratch stocks and sand occasionally. Though carbide router bits work, I avoid using a router with ebony because it creates more dust (a problem for some) and tends to produce clunky profiles. For other shapes, say for pulls and finials, you can use rasps and files.

Tricks for Working with Ebony

No Shame in Faking It

If you are troubled by true ebony’s sustainability, or its pricetag, ebonizing a less-expensive, more common wood is a great alternative. use water-soluble aniline dye powder to transform common woods into jet-black faux Gabon ebony. Finish it well, and it’s hard to tell it isn’t the real thing. Woods that mimic Gabon well are rift or plain-sawn cherry and pear, and to some extent, walnut. And you might want to try ebonizing oak or ash, where the grain remains dominant, but turns deep black. Any surface to be ebonized must be carefully prepped beforehand, sanding, raising the grain, and sanding again (up to 320 grit) until it is polished.

Ebonizing is only skin deep and you can sand, plane, or scrape through it if you’re not careful. So it is not appropriate for fans or inlays, nor small beads or other small moldings that will be planed, scraped, or shaped after installation. Minor sand-throughs can be touched up with a black felt-tipped marker. If you’re using a waterborne clearcoat, seal the dye with dewaxed shellac.

Create Contrasting Details

Ebonizing is easy, and opens up lots of design possibilities. The water-soluble dye powder dissolves in warm water and can be brushed or wiped on. Build up coats until you get the appearance you want.

Ebonizing techniques can also work great for blackening the bottom few inches of a leg or adding a splash of color to a bead.

Comments

As a professional violin maker I work with ebony regularly. Airborne ebony dust is considered to be toxic (not just an allergan for 'some people' so everyone should wear an effective respirator when working ebony with tools or abrasives that create airborne ebony particles. I find that ebony planes much better with a steeper bevel angle (so don't use a low angle plane!). Also, it works very nicely with sharp scrapers. When sanding is desirable, use wet-or-dry sandpaper with water: it cuts nicely, controls loading of the abrasive (clean the sandpaper with a brush in a tub of water as needed) and prevents the dust from getting into the air. After wet sanding, the ebony can be burnished with a dry paper towel for a nice matte finsih, or polished with a little beeswax on a rag. Finally, ebony is not a single species, but a variety of related tropical species from Africa, Madagascar, India, etc.

To ebonize small pieces that will stand some scraping or light sanding, I have used multiple coats of a magic marker. It will raise the grain a bit, and so there is an iterative series of light sanding and marker-dying steps. It's a lot like brushing on analine dye, but penetrates more deeply. It also needs to be sealed with shelac - we have all seen how marker ink will bleed.

you should clarify wether to use a low angle plane. One article contrasts the other.

Ebonizing can be carried all the way through a piece of wood if done properly but it takes study and care.

beautiful

Garrett, Nice article. BTW it looks like you ebonized your thumb nail with a hammer.

What a shame the way we dont appreciate natural things of beauty--

I love ebony and in south Africa our local equivalent

is called "Hardekool" It is white around the sapwood with a hard black core. It is readilly available at the roadside

where hawkers are selling it by the bagful as firewood

regards

fred

I recently used some ebony for the first time on a jewellery box. The results were fantastic well worth the care needed to work it. I too found the a steeper angled plane and a scraper worked best and that when initially dimensioning the stock it took the edge off the table saw blade as if it was made of concrete !!! The only down side, apart from the cost, was that I seem to have a reaction to the dust if it came into contact with my face even though I wore a mask. I think if I use it again I will try wet sanding to try and stop airborn dust particles causing problems.

Hardekool (Afrikaans name), Leadwood (English name), Combretum Imberbe (scientific name) is NOT ebony.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in