"Housewright and jointer" Luther Sampson's 18th century shop

While working on a project at a private school for children in Duxbury, MA, restoration carpenter Michael Burrey stumbled onto a joiner’s shop — previously overlooked, in a small building being used for storage — dating back to the late 18th century. It’s probably the oldest extant American woodworking shop. The owner has been identified as Luther Sampson, a skilled local woodworker whose work can still be found in period houses around town.

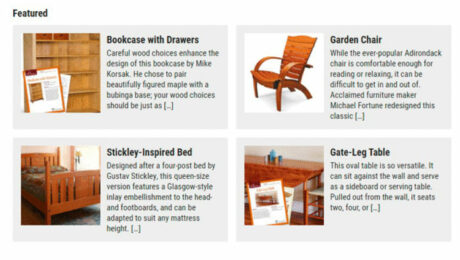

Amazingly, the shop still contains a treadle lathe, racks for chisels and awls, shelves for planes and handsaws, and the original benches. The tools are long gone, of course, but what’s so remarkable is what it suggests about the way period joiners worked.

J. Ritchie Garrison, a history professor at the University of Delaware who specializes in American material culture, visited the shop recently as part of a survey team that includes architectural historian Jeff Klee of Colonial Williamsburg and joiner Peter Follansbee of Plimouth Plantation, among others. On Tuesday, I spoke to Garrison about the significance of the find.

“It’s extraordinarily rare,” he said. I never thought I’d see anything like it — It’s the closest thing to the Dominy shop.” The Dominy shop (the contents of which now reside at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware), contains around a thousand tools from a family of early American carpenters, cabinet makers, wheelwrights, turners, and toolmakers. Their tools survived, but the shop didn’t — which is why the Duxbury shop is so important.

(Here’s a clip from The Woodwright’s Shop, wherein Roy and his moustache visit the Dominy exhibit at Winterthur.)

According to Garrison, the Sampson shop contains the earliest example he’s seen of a central assembly table. It also contains a fireplace, which is an indication of the quality of Sampson’s craftsmanship. Since traditional joinery doesn’t require heat, Garrison explained, the presence of the fireplace (located far from the planing bench, where shavings might be ignited by a wayward spark) suggests that Sampson was using hide glues and finishes. And that suggests that he was doing high-end cabinetry and joinery, in addition to the interior woodwork he was doing for area homes. The shop continued to be used by craftsmen after Sampson; there’s evidence that it was used by chairmakers in the 1800s.

In one of the photos above, you can see a date — “1789” — painted in black on one of the joists. Whether that’s the date the shop was built or not is unknown, but the evidence suggests it is at least that old. A dendrochronologist on the survey team took a core sample from one of the benches, and preliminary findings suggest that it was built with second-growth timber, Garrison says. If so, it provides some insight into both the age of the shop and how much timber had been used in the area since it was colonized in the early 1600s.

The results of the inital survey will take months. “it’s still a puzzle,” Garrison said. In the meantime, Garrison and others are working to raise the necessary funds for the shop’s preservation through public and private channels.

For more neat details, check out this article by Robert Knox in the Boston Globe.

Joiner Peter Follansbee has more photos on his blog, Joiner’s Notes. If early American woodworking is your bag, Joiner’s Notes is definitely worth checking out.

Architectural historian Jeff Klee has more photos, with much higher resolution, on his flickr page.

Comments

What a wonderful find. From the design of the loft stairs, one might assume that Mr. Sampson had a good sense of balance.

Out of the twelve pictures I found myself looking at the stairs too.

A wonderful photo essay garnering comments from people who would live this well if the world would let them. The photo of the wrought strap hinge is outstanding of what "thinking hands" can create. What I would like to see more of is the "drive wheel" shown partly in the ceiling with an attached floor treadle ...probably hooked to a wood lathe.My first observations when told of this find was skepticism which is now abated once more photos have come forth.

There are several English 18th century paintings of the interior of cabinet shops so this is a welcomed edition. I say "cabinet" shop and not "joiner's" shop because cabinet makers and joiners are distinguished by one using glue, the cabinet maker, and the other, the joiner, not. So perhaps in the normal "American" tradition the craftsman in this shop was multi-flavored...god bless. As to this artifact being a "revolutionary era" shop...one trusts not only a political revolution, but also a stepping stone into the industrial revolution looming large in the market place.

Now comes the demanding task of cleaning the place of detritus while at the same time not destroying its significance as as artifact...keeping in mind its restoration is about it, and not about the aesthetics of the restorers.

Richard O. Byrne

iphone 4 cases

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in