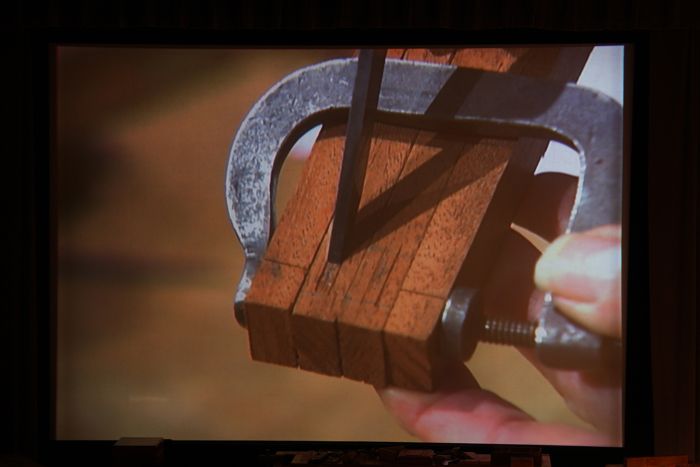

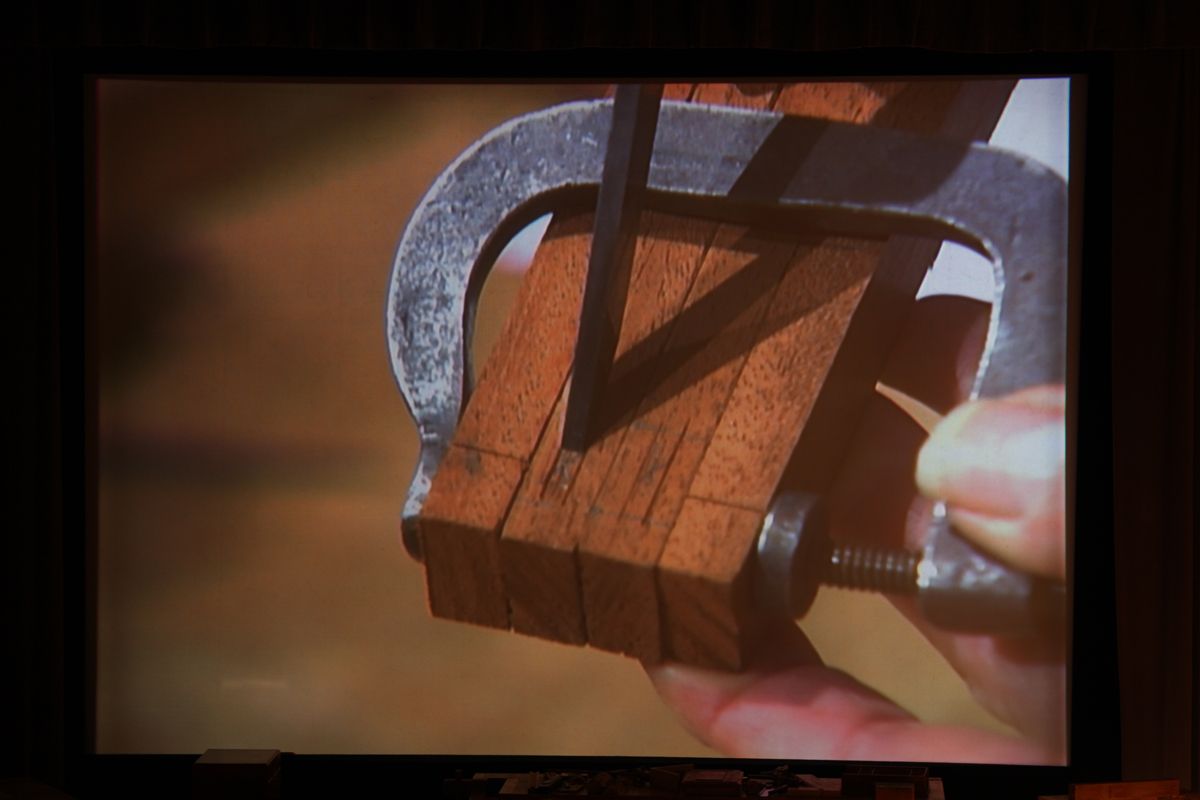

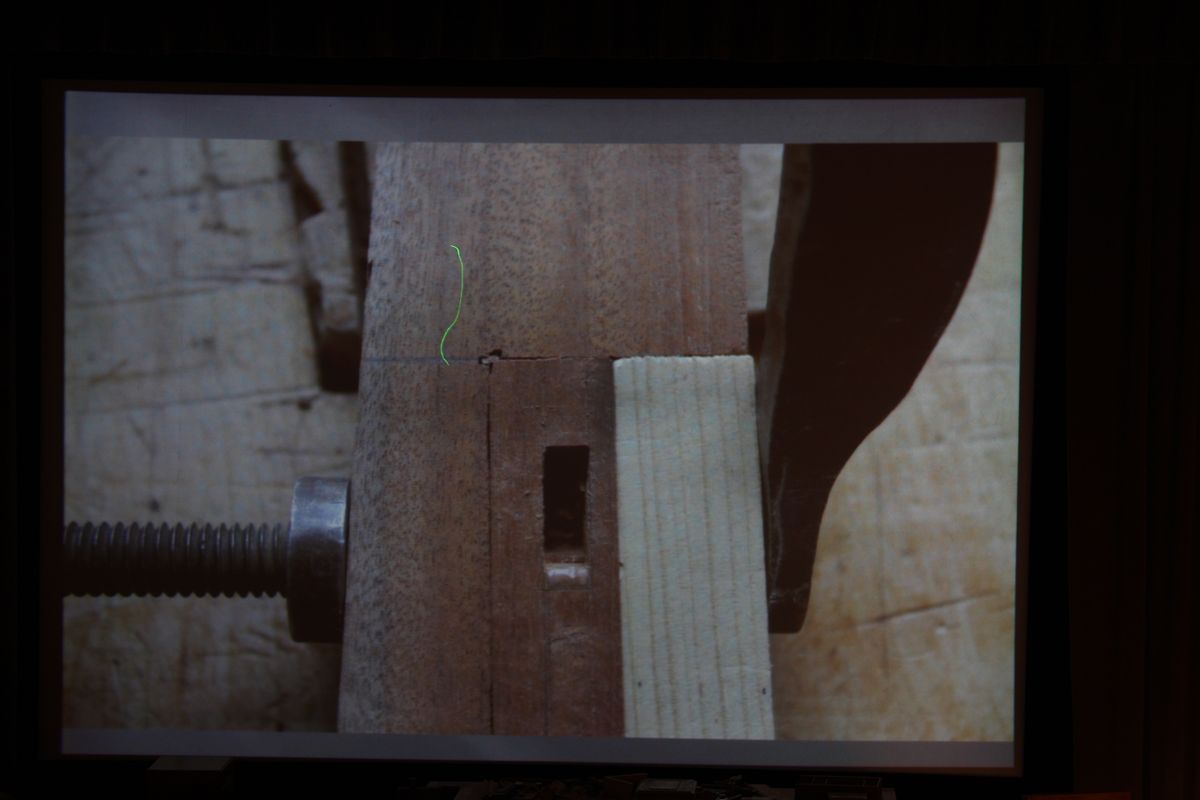

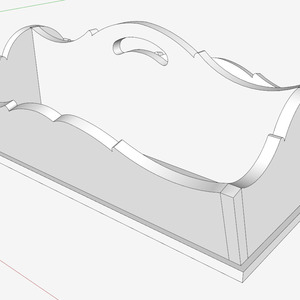

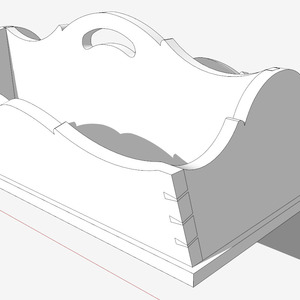

Gang narrow stiles. These parts are just 5/16 in. thick. To keep from blowing out the sides of the mortises as he chopped them, Kaare clamped the rails and stiles together.

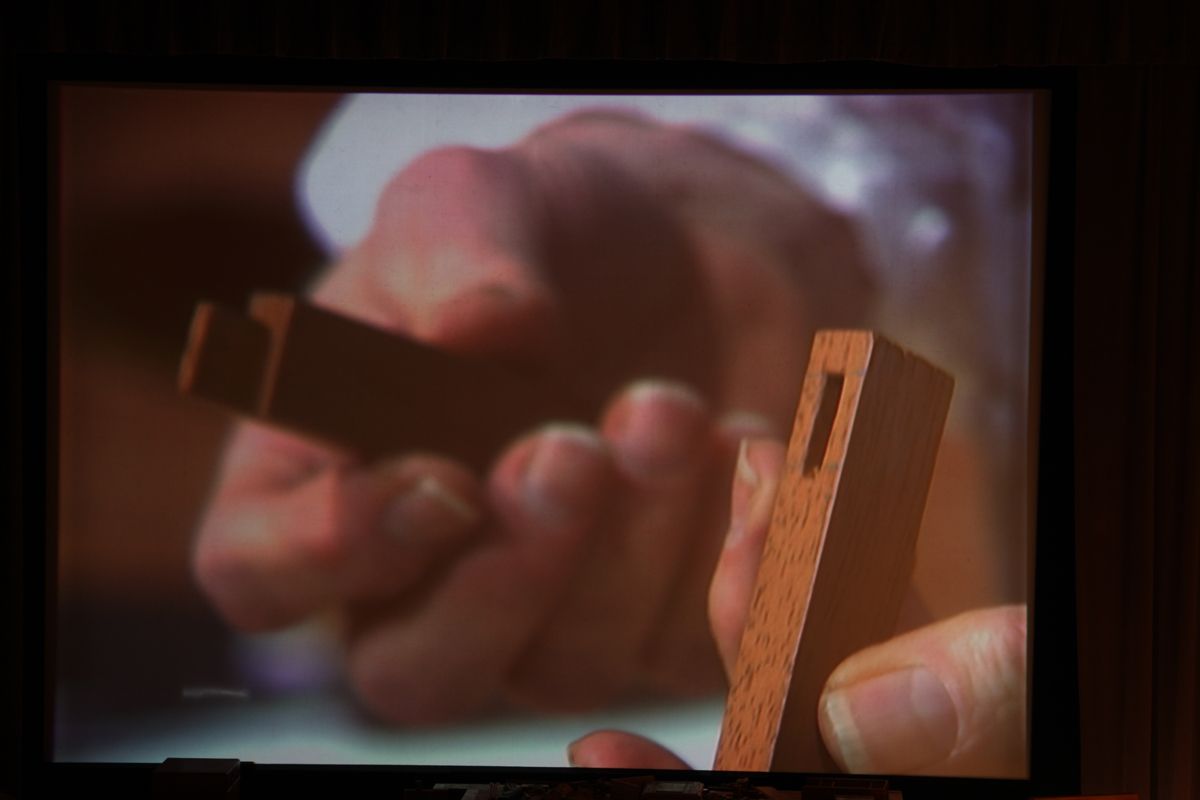

The topic of this year’s Working Wood in the 18th Century conference at Colonial Williamsburg is, basically, small stuff like traveling boxes. Journeyman cabinet maker Kaare Loftheim undertook the daunting task of reproducing a small bracket clock. (The name comes from how the clock movement is mounted in the case. These are clocks that might sit on your mantel or a bookshelf). The case has a very small face frame on it. The rails and stiles of the frame are just 5/16 in. thick. The door on the case has a thin frame, too. Those parts are 9/16 in. thick. So, Kaare need to chop mortises in some insanely thin parts. The greatest potential problem he faced was blowing out the sides or end of the mortise when chopping it. Take a look at the photos to see how he dealt with those dangers.

You might be wondering, like I did (and I asked Kaare about this) why he didn’t leave the stiles long, so that there was a horn on both ends. That greatly reduces the chance of blowing out the mortise’s end grain. He had a good answer: He was making the clock case from some very choice mahogany and simply didn’t have enough to waste some on horns. Sometimes, practicalities like this force us to adapt from our usual techniques (Kaare said that they normally do leave horns on the stiles when making doors.) I think he did a great job of adapting.

See all of the coverage from the Working Wood in the 18th Century conference at Colonial Williamsburg.

Comments

Definitely a good technique. I usually use a wooden handscrew for this same task, but the spare blocks / c-clamp would also work well.

great technique,,,,but mate, maybe time to trim those nails, hmm?

I have used this technique many times. On such small tenons, the shoulders are very narrow so any tear out around the face of the mortise will show. To minimize this, I put down a piece of masking tape on the mortise face before marking. Then use a cutting tip in my marking gauge, which cuts through the tape and provide a nice knife line. The masking tape being much brighter than the wood provides an excellent visual guide. May be overkill, but my old eyes really benefit from it.

I wonder sometimes if finding the hardest way to do things is a prerequisite for woodworking. I find drilling out the waste first then trimming with a sharp knife or chisel prevents the pressure that would cause blowout.

teamwinner,

Although I wouldn't have done the mortises as Kaare did, neither of us has the same constraints on his technique as Kaare does. Recall that he is working as cabinetmakers did in the 18th century. What Kaare is doing is generally faster than drilling out the waste with a brace and bit and then squaring up the mortise. It's probably easier to get an accurate (i.e., square) mortise his way, too. Of course, if the cabinetmaker had a drill press available to him in the 18th century (or, even better, a hollow chisel mortiser), things would be different.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in