7 Lessons for the Aspiring Furniture Maker

The best thing to do is a join a club or guild. The more involved you get, the more you will learn.

by Monica Raymond

from FWW #217

In 1985, I announced to friends and family that I was dropping out of college to build a house. I was surprised when several people asked, “What makes you think you can build a house?” It had never occurred to me that I couldn’t. My reply was, “People build houses. I’m a person; therefore I can build a house.”

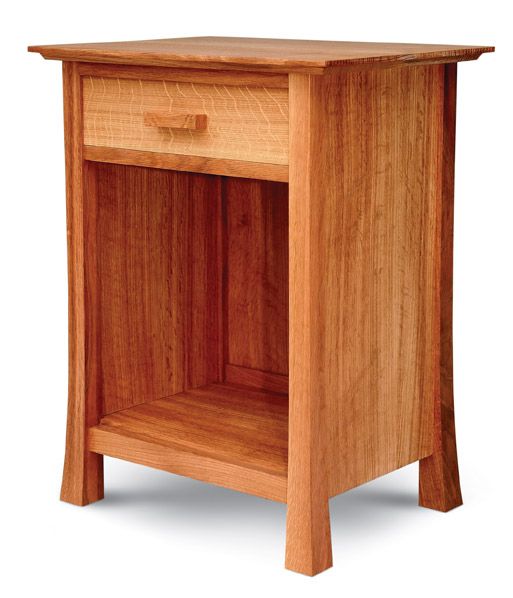

Completing that house took many years and plenty of blood, sweat, and tears, but is my proudest accomplishment. And now that experience is bearing fruit as I pursue another passion: making furniture.

If you dream of building furniture but don’t know where to begin, or if you are not progressing as fast as you’d like, read on. I won’t tell you how to make furniture, but I do have some advice about how to learn. I’ve already shared Lesson No. 1: Believe in yourself.

Lesson 2: Take a class I thought that my carpentry skills qualified me to build furniture, and so I made a few tables and cabinets over the years, but nothing ever came out very well. I was about to give up entirely when I wondered if my feeble skill level was due to a lack of training rather than some personal defect. A few months later, I took a two-week basic fine woodworking class and my skills took a quantum leap.

Don’t struggle for years like I did before taking a class! Woodworking books are very useful, but if a picture is worth a thousand words, seeing a live woodworking demonstration is worth a million. And when the demo is followed by hands-on practice and feedback, it’s priceless. In a class, you learn specific techniques for every part of the furniture-making process. If at first you don’t succeed, the instructor can diagnose and correct your mistakes. Even when you make a blunder that seems irreparable, the teacher usually knows a way to fix it.

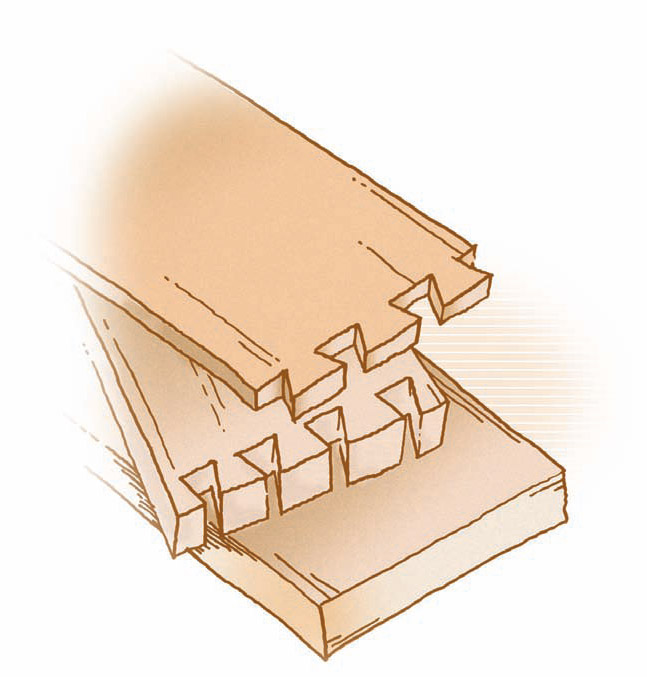

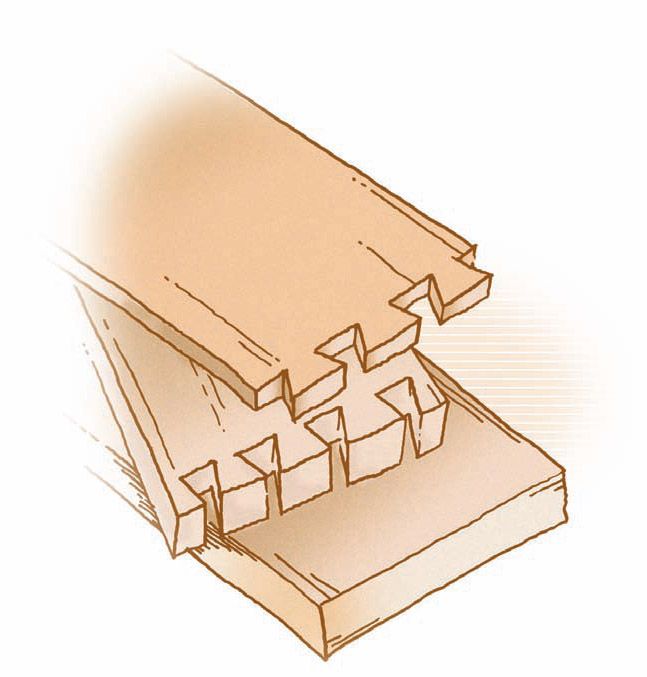

The technique I was most excited to learn in my first class was dovetails. So, my first project after the course was a blanket chest with 40 hand-cut dovetails. I now knew that starting with perfectly flat boards was essential, but there were still some gaps in my knowledge. While I had learned how to flatten and square a single board, my jointing skills were not great and my handplaning skills (actually, my sharpening skills) were poor. I got around this by using a friend’s drum sander to flatten the wide glueups. But unlike my first woodworking experiences, which left me frustrated and demoralized, these failures simply motivated me to enhance my skills. Having attended a class made me realize that I could improve, and I knew how to make it happen.

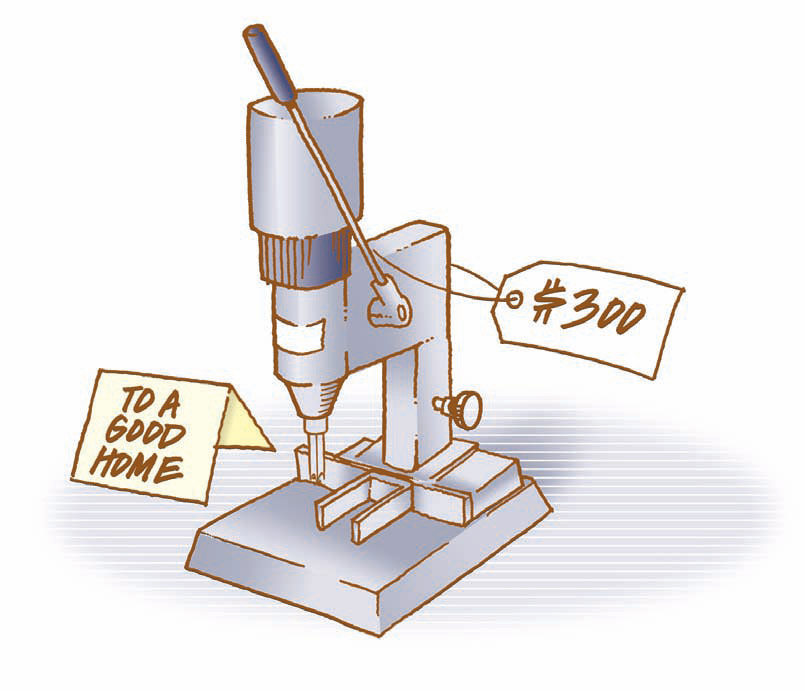

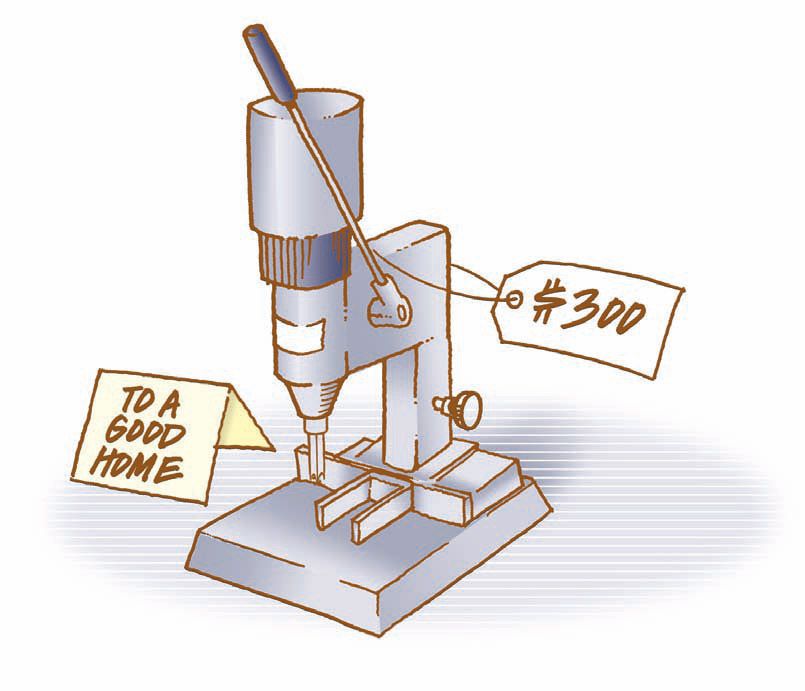

3. Find woodworking friends and mentors Other than taking a class, one of the best decisions I made was to join the Guild of New Hampshire Woodworkers. This all-volunteer organization has been my greatest source of support, not to mention pure enjoyment. The Guild holds a variety of meetings, mostly mini-courses on a plethora of topics. I always take fellow woodworkers up on offers to visit their shops. Not only do I learn a lot with every visit, but I also have acquired a cadre of mentors and friends who generously help me and advise me.  For instance, when my friend Jon Siegel learned I was selling my hollow-chisel mortiser because it didn’t work well, he offered to help diagnose the problem. He determined that my bits needed reshaping, which he did for me in his own shop. When he visited my shop to return the bits, he spent hours showing me how to better tune and maintain the mortiser. We also discussed the qualities of the cherry I had gotten for my next project. He taught me about sharpening with sanding belts vs. stones, and showed me how to tune the guides on my bandsaw.

For instance, when my friend Jon Siegel learned I was selling my hollow-chisel mortiser because it didn’t work well, he offered to help diagnose the problem. He determined that my bits needed reshaping, which he did for me in his own shop. When he visited my shop to return the bits, he spent hours showing me how to better tune and maintain the mortiser. We also discussed the qualities of the cherry I had gotten for my next project. He taught me about sharpening with sanding belts vs. stones, and showed me how to tune the guides on my bandsaw.

There are a number of ways to find woodworking friends. Woodworking-supply stores often hold events and classes, which are good places to meet people. You can also find folks by taking a class at a nearby woodworking school that caters to locals. Perhaps the best thing to do is join a club or guild and attend as many events as you can. The more involved you get, the more you will learn.

4. Stick with your old machines for a while One of the greatest challenges facing a new woodworker is deciding what tools and machines to get.  Ask other woodworkers what they use and why. However, don’t take their answers as directives, but as information to use in making your own unhurried decision. Consider your own style of woodworking in deciding what is most important to you.

Ask other woodworkers what they use and why. However, don’t take their answers as directives, but as information to use in making your own unhurried decision. Consider your own style of woodworking in deciding what is most important to you.

If you already have machines made for the hobbyist or carpenter (or can buy them cheaply at yard sales), use them to make furniture for a while. The experience will teach you which features are most important to you and help you make a more informed decision when you upgrade. For example, when using my old jointer for making furniture, I quickly discovered its limitations: at 6 in. it was not wide enough, and it had a sloppy fence that was impossible to adjust finely and tables that were too short and not coplanar. Other than moving up in size, my main considerations when replacing it were getting a brand known for precision manufacturing and a model with a fence adjusted by a handwheel.

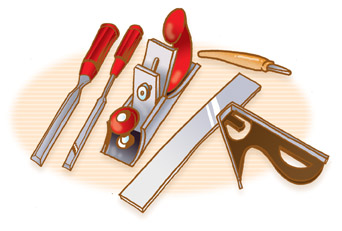

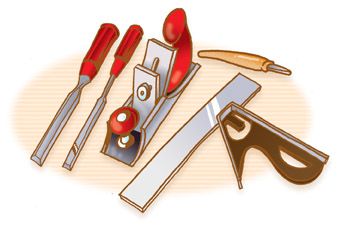

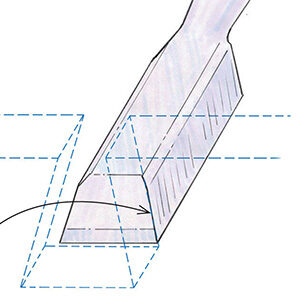

5. Get good hand tools right away When it comes to acquiring hand tools, my strategy is different. These tools are used for the most critical tasks: measuring, marking, cutting joinery, and eliminating machine marks, among other things. These tasks play a greater role in the quality of the final product than almost anything you do with a machine. Therefore, they must be effective and accurate. If your square is not square, it is useless. During my first woodworking class, I tried marking the shoulders of a tenon with my old carpenter’s combination square and found the lines didn’t meet. I realized it was impossible to make a tight-fitting joint without an accurate square. Although I was stunned by the cost of top-of-the-line squares, I bought a 12-in. one and a 4-in. one, and now I can’t imagine getting along without them.  The good news is that handplanes, another shop staple, are relatively easy to get inexpensively if you buy them used. There are a few older brands such as Stanley Bailey and Bedrock that are of much better quality than new planes of similar price, though you’ll probably need to spend time tuning them up (see Make a Bargain-Basement Plane Perform Like Royalty, FWW #217). It’s also a good idea to buy quality replacement blades. On the other hand, if you have more money than time, buy top-of-the-line new handplanes.

The good news is that handplanes, another shop staple, are relatively easy to get inexpensively if you buy them used. There are a few older brands such as Stanley Bailey and Bedrock that are of much better quality than new planes of similar price, though you’ll probably need to spend time tuning them up (see Make a Bargain-Basement Plane Perform Like Royalty, FWW #217). It’s also a good idea to buy quality replacement blades. On the other hand, if you have more money than time, buy top-of-the-line new handplanes.

6. Practice, practice Once you’ve gotten various hand tools, taken a class, and established a set of woodworking friends, how do you go about actually improving your skills? Practice, practice, practice. Although it’s probably ideal to do exercises such as jointing a hundred boards or doing a hundred dovetails in a row, I prefer to practice while working on a project. For example, before I do a piece with dovetails, I practice dovetails on scrap lumber until I get them right. Later, if I’m not satisfied with how it’s going, I might put the piece aside and spend an hour or more refining my technique.  It’s also important to eliminate distractions and pay attention. For years I was not able to cut a straight line with a dovetail saw. Finally, I analyzed my technique and realized that my wrist twisted to the right at the end of each push stroke. I have to concentrate to correct this. If I find myself straying, I pick up some scrap and do 10 or 20 practice cuts.

It’s also important to eliminate distractions and pay attention. For years I was not able to cut a straight line with a dovetail saw. Finally, I analyzed my technique and realized that my wrist twisted to the right at the end of each push stroke. I have to concentrate to correct this. If I find myself straying, I pick up some scrap and do 10 or 20 practice cuts.

It helps to make a piece that involves several repetitions of a skill you want to improve. If your project only includes one drawer, for example, you won’t get an immediate chance to make the second drawer better than the first. By the time you make another piece with a drawer, you might have forgotten what you wanted to do differently. Frequent repetition-whether in practice or on a piece-is an excellent way to learn. Eventually, as you develop your eye and your muscle memory, you will be able to retain your skills longer and need fewer practice sessions.

7. Rely on your own experience My final recommendation: Don’t blindly follow anyone’s advice, mine included. Seek and listen to advice, but just put each bit “in the hopper” with all the other contradictory opinions. Experiment with the ideas that resonate most with you. In the end, take everything you’ve read and all the viewpoints you’ve heard, evaluate them through the filter of your own experience, and distill the formula that works best for you.

What lessons have you learned in woodworking? Have your own advice for aspiring woodworkers? Share your thoughts below in the comments.

Comments

Best advice I've seen in a long while.

Thanks!

You are absolutely correct. I started taking classes after I had been woodworking for 35 years. My first was to learn to make shaker boxes, which lead to me making several for the cremanes of close friends.

Since that time I've taken several each year. This March I'm signed up for a class with Garret Hack at the Woodworking Showcase in Saratoga Springs, NY to learn to a bead scratch stock.

I have learned so much taking classes I wish I had started years ago. No one person knows it all and you just might learn something from a new friend you meet in a class.

Great article, thanks for publishing

.....no truer words have ever been spoken.....

Great read. thank you.

#8 (or 3b) Make friends with old woodworkers. I got my first table saw (and a lathe) from a guy for free because he already had 2 and knew a lady who was getting rid of one because it was collecting dust in her garage. The old guys are full of experience and wisdom, seem to know everyone in the neighborhood and always like to talk shop.

Love to be part of this community. what a blessing.

josh.

Thanks for sharing your journey and the great tips. It sounds very familiar. Now out to the shop and put a finish on a small oak side table I completed earlier this week. Thanks again.

Monica,

Now it's time for you to do what I started doing recently. I established a vintage and antique hand tool restoration class through our local adult school. I started with Ron Herman's saw videos, then hands-on lessons sharpening saws. Lesson two will focus on restoring all types of planes. Lesson three on chisels, and so on.

There are plenty of younger folks out there who want to get started in woodworking, but can't afford expensive power tools, or high en hand tools, so we teach them to restore and reuse. And in the class setting we can also learn technique. I'd bet you have plenty to pass on.

Inspirational article; a good starting point.

I'll take this opportunity to pass on a bit of advice that was given me by an old foundry pattern maker many years ago: He told me that the measure of a craftsman isn't how good one is with the finest tools and machines, but what one can do with the tools one has at hand. The best tool isn't necessarily the prettiest, the shinyest, or the most expensive - it's the one that does the job the way one wants it done. Sometimes that depends on how well one has learned to use that particular tool.

And lastly something I've found myself through experience: Learn how and develop the skill to sharpen your tools properly - even handsaws, if you use them. Dull tools are the pits.

My wife said she agreed that I should retire but said that I had to have something to do on Monday morning. A week making a Windsor chair with Tom Thackray was fixed .. One to one.. Starting with 'have you ever turned Don?'. By lunch break I was turning legs.. By Friday 5 pm I was on my way home with a finished Stickback in the back of the car..weeping with joy!.19 years later I love making them in 3 sizes.as well as settles, rotating bookcases, bowls, platters all because of Tom giving me the confidence to do it as your super article tells us. Best wood mag in the UK... thanks

Great advice! Thank you!

Chris Mobley

http://www.cmobleydesigns.com

I began woodworking by making toys, shelves and other simple things. But my first exposure to furniture making began years before that with my great grandfather. Many years after his death, I made my first piece of furniture, a coffee table. I made it for one simple reason, I needed one. From there it has been end tables, a telephone table, several desks, and so on. I always had the confidence, and I'm pretty good at back engineering. I will look at a piece, examine it, and know in my head how to duplicate it with my own design changes if desired. I began with a jig saw and a circular saw and a hand held electric drill plus the usual hand tool like a hammer, screwdrivers and so on and built my collection from there. I too have always wanted to build a house, but I'm at the age now where I'd like to HAVE one built while I watch.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in