The Why of Windsor Chairs

A veteran maker explains the roots, the rationale, and the powerful appeal of America’s classic chair style.

Synopsis: Four centuries after they first emerged, in England, Windsors chairs and their offspring account for about half the wooden chairs on the planet. The original chair has spawned a multitude of different varieties and designs. What makes the Windsor so iconic? Pre-eminent Windsor chair maker Curtis Buchanan takes a look at the chair’s history, its structure, and its materials, then takes us through a gallery of different Windsor designs. Also included: a glimpse into what it’s like to work in Buchanan’s Jonesborough, Tenn., shop from day to day.

Windsor chairs are enduring. Three centuries after they first emerged, in England, Windsors and their offspring account for about half the wooden chairs on the planet. Post-and-rung chairs and their descendants account for the other half. The Windsor got its robust DNA from the 17th-century Welsh stick chair. With a thick seat made of elm, and legs, stretchers, and arms hewn from hefty pieces of white oak, the Welsh stick chair was a tank with style. Instead of being made cabinetmaker-fashion with a skeletal structure and rectangular mortise-and-tenon joints, it had “sticks” socketed into the top and bottom of its seat to make its back and its undercarriage. English makers adopted this method of construction for the Windsor, and by the 1730s some of their new chairs—probably comb-backs—crossed the Atlantic and landed in Philadelphia, where the Windsor style promptly caught fire.

Soon woodworkers in other colonies responded with their own versions, some based on English designs like the sack-back, and others, like the continuous arm, proudly American. Here the once-beefy Welsh chair was transformed into a slender and resilient chair without an ounce of extra weight. Unconstrained by the guilds that strictly regulated English chairmaking, colonial makers experimented and innovated. By the time the Constitution was written, Windsors were the most popular pieces of furniture in the country. Ships that entered northern harbors with loads of cotton from the south filled their holds with Windsors for the return. Up and down the eastern seaboard, Windsors graced farmhouses and statehouses, mansions and barrooms. They were used by the wealthy for seating in the kitchen, on the porch, and in the garden, and by the common man as his one chair, moved to wherever he wished to sit. What made Windsors so popular and enduring? The answer starts with their structure.

The seat is the anchor

The seat of a Windsor is the keystone of the chair, anchoring the undercarriage and the upper structure. Without the seat, all you have is a handful of sticks on the floor. In a post-and-rung chair, by contrast, the seat is added after the structure is complete. In a Windsor, the seat not only ties the whole chair together structurally, but it also trestles the chair together visually. As the largest mass of solid wood on the Windsor—the rest being mostly air— the seat draws your eye first.

Windsor seats need to be thick to allow for long mortises and for deep sculpting of the saddle, but they’re usually carved from soft, light wood, and the whole chair can come in at less than 8 lb. That’s incredible for a chair that can hold a 200-lb. person comfortably, day in and day out, for many years.

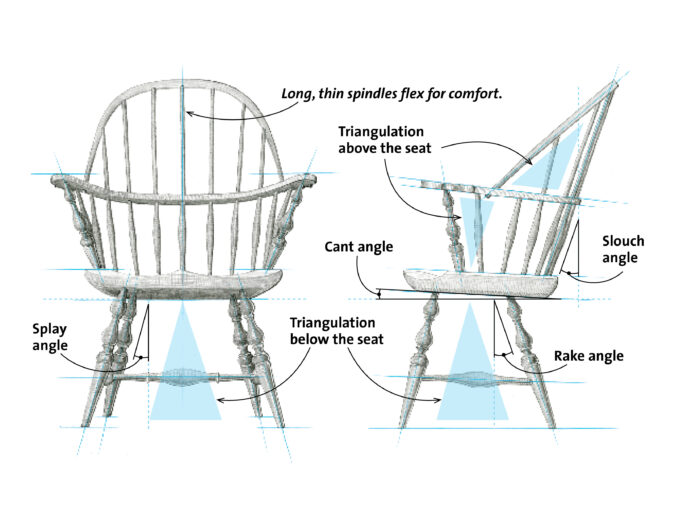

The Windsor’s strength and durability result from the fact that its parts are triangulated. Its outward splaying legs create opposing forces, for a very firm foundation. And on armchairs the forward-leaning arm supports help constrain the force of the sitter’s weight against the back. Conversely, a traditional post-and-rung chair, with its parts perpendicular, has to rely on its small joints to resist racking forces—a losing proposition. Windsors, with triangles everywhere, naturally resist racking.

Windsors are also made to flex, which reduces strain on their joints. And because they are traditionally made from split stock, their continuous-grain parts have maximum resilience—the ability to bend under load without breaking—which is a boon for comfort as well as durability.

Windsor engineering

Despite their light weight, Windsors are incredibly strong, thanks to clever engineering. Below the seat, triangulation provides resistance to racking; above the seat, it counteracts backward momentum. Rake, splay, slouch, and cant angles differ by style of chair and by use. Dining and desk chairs are more upright, living room chairs less so. For a detailed look at these angles, go to FineWoodworking.com/extras.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in