How to Think Like a Carver

Being able to rewind the clock and figure out what the first moves a carver made on any given project is tricky to do

Being able to rewind the clock and figure out the first moves a carver made on any given project is tricky. The inclination of novices is to draw in the final cuts right away, when that is really the last 5%.

The important questions are:

What did the work look like before any of the details were added?

This requires breaking down the work into its most basic masses and shapes. This is the framework of the carving, the proportioning of the parts of the carving, and their relationship to one another in place and size.

Being able to think about the process boils down to deciding what the first cut will be. Try not to worry about the last cut. By the time you get there, it will be obvious. All the last cuts are right in front of you, but the first ones are long gone.

When can I move a lot of wood fast, and when do I slow down?

This obviously is closely related to the previous question. Once you’re confident of the basic shapes, you can hack away at the extra material to get there. This requires a certain amount of bravery for the beginner because knowing where to stop is usually a function of having gone too far previously.

This is called experience, and as scary as the process may be, we are dealing in wood here, and it can be glued back on or replaced with a new piece. It is rare to commit a show-stopping error. Most of the time the work can be slightly modified to correct the problem. A ball-and-claw foot lives in a space that is from 0 to 3” off the floor, not a place where most observers will be concentrating on. Try to think about an order of importance: In a chair the crest gets most of the attention, the knees less, and the feet hardly any.

How do you make sure similar parts (let’s use ball-and-claw feet) are identical?

Having measured many period feet, I can assure you that there can be a great discrepancy between feet on the same piece, and no one except another carver measuring it will ever know.

In making multiples the carver has two things that help a great deal. One is that the farther away the elements are from each other, the more similar they become. Holding two feet next to each other is a good measurement to see how you’re doing, but they will never be that close together again.

Hold them 2 ft. apart and notice how they become a perfect pair. Secondly, and maybe more importantly, observers assume that like parts are identical and so their brains make the adjustment to make it so. This works for the craftsman wonderfully well in all sorts of situations: knee and foot carving on chairs and tables and lines of spindles along balconies, for example. Just the word “set” of chairs presumes they are all identical.

So to think about carving is to construct the process mentally before making chips. What’s high, what’s low, what are the basic shapes? Do this and you will become more adept at choosing the right size and shape tool for the job, (a subject for a future discussion) and carvings will stop looking so scary.

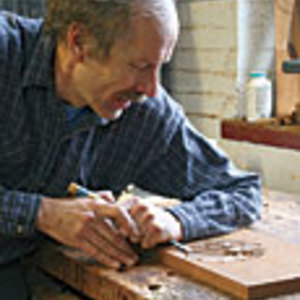

-Allan Breed is a full time reproduction cabinetmaker in Rollinsford, N.H., where he also teaches carving and hand-tool cabinetmaking. Allan can be found online at www.allanbreed.com and has an active instagram account.

Comments

Wonderful article and world class carving. A joy to read and observe as well. Thanks for sharing your skills, Allan Breed.

Oh that I had the skill and patience for carving!

Federal furniture elements tax me enough with stringing and banding and such.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in