Survival of the prettiest

Sometimes the worst thing you can do while copying an antique is to actually copy the antique.

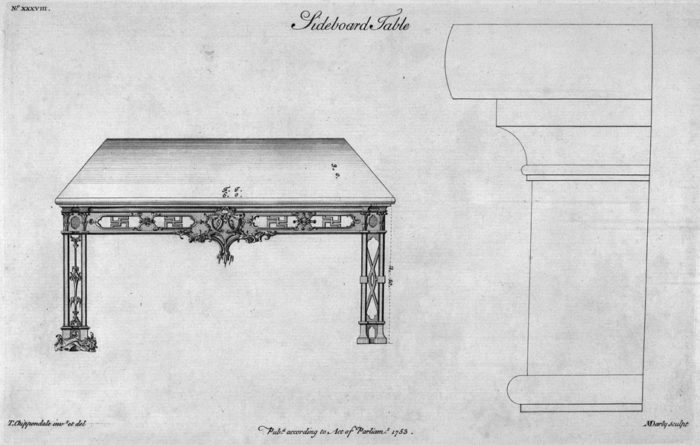

Sometimes the worst thing you can do while copying an antique is to actually copy the antique. The sideboard table pictured above is one of the most ornate and iconic examples of fine furniture from 18th-century Virginia. It is, to my mind, a stunning object. Its abundant ornament is carefully orchestrated to please the eye without overwhelming it—a rare achievement. Likewise, the imported marble top is a perfect marriage of luxury and practicality (serving hot dishes from a marble surface rather than wood makes a lot of sense). All of this inspired my colleague, Kaare Loftheim, and I to re-create the table as soon as the chance arose four years ago. Unfortunately, we soon discovered what everyone else who’s gotten close to this beautiful object has discovered: It’s a lousy table.

Yes, you read that right. This masterpiece is not a well-constructed piece of furniture. That inconvenient fact didn’t stop us from going forward with our project, but knew we’d have to make some changes.

First, let’s consider the table and its history more closely. Currently owned by the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), the table was originally built for the Tayloe family of Virginia in the early 1760s. The interior of their home, Mount Airy, was designed and constructed by the joiner/architect William Buckland ,who also designed and oversaw construction of the sideboard table. Its many carved, architectural moldings repeated patterns featured throughout the home’s dining room, though its overall design and central element were clearly inspired by a plate in Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinetmaker’s Director— a book listed among Buckland’s possessions.

William Bernard Sears (who worked with Buckland often) did the carving and all of it, except for the elements that run down the center of each leg, was applied to the table’s structure rather than carved out of it (that’s not unusual, especially for workmen so accustomed to architectural ornament). On the surface, the table is a successful blend of English rococo design and classical architectural elements that, once placed in its original setting undoubtedly lent an air of old-world opulence to a colonial Virginia home.

So what’s the problem with this table? Let’s start with the legs, or actually the combination of those long, pierced legs with that marble top. Chippendale published this particular sideboard in all three editions of his book (1754, 1755, and 1762). Buckland probably did not have the 1762 edition. Why not? Well, that’s the only edition in which Chippendale praised the pierced legs for their “airy look,” but then warned that they’d be “too slight for Marble-Tops.” Perhaps he learned of this unwise combination in the years between the second and third editions or just thought to add the warning. Either way, Buckland learned the hard way. Though the legs started out as substantial blocks just over 4 in. square in cross section, most of their mass was sawn out to make way for the piercing. Perhaps cross stretchers would have helped solidify things, but they were never part of the plan, so these considerably weakened legs were tasked with holding up a slab of marble that must weigh in the neighborhood of 150 lb. plus heavy plates of food ready to be served. Conservators believe that within the table’s first decade or sooner, large walnut blocks were added back behind the pierced work to keep everything from falling apart. For over 200 years, the intended “airy look” was gone, though the table was still quite stylish.

MESDA has since removed the walnut support blocks to restore the open fretwork of the legs. The marble top now hovers a fraction of an inch above the table, supported by a steel frame below. That works for a museum exhibit, but not for a functioning table. In our reproduction, Kaare and I opted to use a walnut top, though wood painted to look like marble would have also been a viable period option.

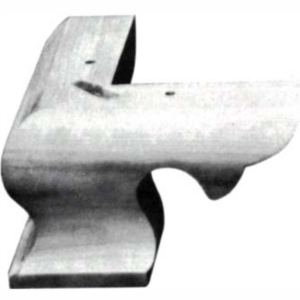

Had Buckland gone with a walnut top instead of marble would the table have been able to escape the addition of those walnut support blocks? That’s pretty unlikely because of the table’s second near fatal flaw: the joinery. Mortise-and-tenon joints can withstand a fair amount of abuse and support a lot of weight when they’re properly made, but when they’re made as they were on this table you’re going to have to add support blocks or just watch all that nice carving crash to the floor. Even when we account for the distortions wrought by two and a half centuries, these joints were clearly ill-fit from the beginning. But their real problem is that the mortises have no bottoms. The picture here shows the joint as seen from below. With no bottom and poor surface-to-surface contact for glue, all that’s holding these legs to the rails are the pins driven through each tenon—the screwed-on L-blocks were added later.

This could have been a mistake of design like the combination of a marble top with pierced legs, but I suspect it was one of execution. It’s an educated guess, but I think the original workmen followed the same order of operations in constructing the legs as I did. After squaring up the leg stock, the mortises were laid out and chopped. Next, an angled sawcut was made to define the upper boundary of the L-shaped recess in each leg (see the photo below). I followed this with another angled saw cut a few inches below the first and then chiseled out the wood in between to form a square pocket that gave my saw space to move as I cut away the remainder of the leg to create the L-shaped cross section. Because there was already a strong layout line to define the bottom of the mortise, the workman could have unthinkingly made his first angled cuts right on that line, thereby erasing the bottom of the mortise. That’s an easy mistake to make, but should have been a hard one to let slide. Kaare and I simply took ¾ in. off the width of each tenon (they’re still plenty big) so we could raise the bottom of the mortise a sufficient distance up from the leg recess.

Here’s the table Kaare and I made. It is quite different from the original, but we feel we’ve captured its spirit. We stand by the changes we made and, more importantly, the table stands on its own.

It’s important to respect antiques and all they represent, but it’s equally important to respect the power of hindsight that we can bring to a reproduction. The challenge for us often lies in finding ways to honor the past without following it blindly. Buckland’s table teaches us a tough lesson about durability, too. No matter how poorly this may have been constructed, there’s no getting around the fact that it’s still here after 250 years. The more I study antiques, the more I believe that the celebrated notion of built-to-last doesn’t necessarily mean bombproof construction. Instead, built-to-last means that a piece is worth repairing and keeping around. It’s survival of the fittest most often, but sometimes it’s survival of the prettiest.

Comments

I don't know what others may think, nor am I really all that concerned, but myself being an extremely experienced novice woodworker, my eyes find the replication much more appealing than the original. The legs, undoubtedly look less spindly and less apt to collapse. And just the overall design changes, to me, look, not only more stylish, but also more timeless.

I agree with David, the "extremely experienced novice" on all his points.

great article. Made me feel better that these masters could also make joints that aren't perfect, on works of art. Like me! hahahahaha

Having inspected the insides of some very nice pieces from the late 1700's, I must agree that some of the principles that we take as ironclad made little impact on those guys. But........I see a tall clock from 1790 that is still running; a highboy from the same era that is holding together despite some inner joinery that makes me shudder.

Super interesting, and well done. Bravo.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in