The history of the cove-and-pin joint

Megan Fitzpatrick explores the history behind the Knapp dovetailing machine, one of the first machines to efficiently manufacture first class drawers

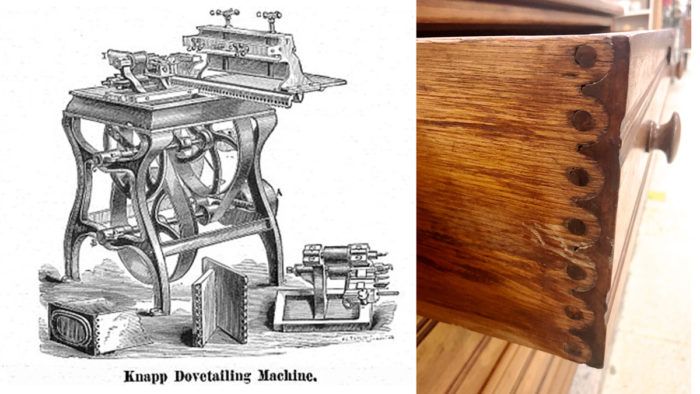

If you have an antique piece of furniture that features drawers with a curious-looking half-circle joint, you can be almost certain that it was made in a North American factory between 1871 and 1900. While it came to be known as the Knapp Joint, the joint is also variously described by its appearance: the pin and cove, scallop and dowel, scallop and peg, pin and scallop, and half-moon.

Why the (rather brief) departure from dovetails? By the second half of the 19th century, most furniture in America was made by machines in industrialized factories—with the exception of fine drawers. Though people were patenting machines that could produce dovetails (106 patents for the like applied for between 1833 and 1900!), no one had yet developed an appealing way to cut more than one uniform pin and tail at a time. (See the Burley & Putman Dovetailing machine, patent nos. 12,122 and 26,647)

See a modern maker’s take on producing a cove-and-pin

joint with common woodworking machinery

High-quality drawers were still being produced by hand, and while a skilled craftsman could turn out perhaps 20 drawers a day, that wasn’t nearly fast enough to keep pace with the production of furniture for which said drawers were intended. Handwork was holding up the factory output.

Instead of focusing on a machine for cutting dovetails, Charles B. Knapp, of Waterloo, Wis., simply rethought the joint.

His 1867 patent (no. 63,532) describes his inventive approach as “of that class of joints known by the general name of a ‘tenon and mortise joint,’ the particular form of the tenon in this instance being in cross-section, round or circular, with the mortise or hole of a corresponding shape and size thereto, so that when placed one within the other they will form a close and tight joint.” It’s a series of semi-circles with a hole in the middle cut into the drawer side that match negative semi-circles with integral pegs in the ends of the drawer front.

Another Eastlake dresser with Knapp-jointed drawers.

In 1870, Knapp sold the rights to an improved version of his machine (patent no. D4,302) to a group of investors who formed the Knapp Dovetailing Company in Northampton, Mass., and he was listed on an 1872 patent (no. 122,390), along with Nathan S. Clement, for improvements to the original design. (On an 1888 patent, no. 388,760, Clement is listed as the sole inventor of a “dovetailing machine” that rethought the technology, though not the joint itself.)

In 1871, the Knapp Dovetailing Company put the machine into a production line at the Beal & Hooper furniture factory in East Cambridge, Mass., and during the next 30-odd years, the technology was embraced in furniture factories throughout the Northeast, with more modest use in the Midwest and Canada. (It never caught on in the United Kingdom or Europe, where hand-cut dovetailed drawers were produced until the 1930s.)

Advertisements from the machine’s heyday claim that it could turn out as many as 400 drawers per day, although furniture historian Fred Taylor puts the number at around 250. At either rate, it’s a marked increase over the number of hand-cut dovetailed drawers that could be produced in the same time.

Taylor writes, the machine, which had nine cutting heads, “was a complicated affair involving five cutting parts. It had an auger, a hollow auger, two V-shaped cutters, and a circular cutter. The auger bored the holes in the drawer side, the hollow auger gouged out the pegs from the drawer front, and the rest of the cutters shaped the circles around the holes and the pegs.”

By 1900, the new and obviously machine-made joint became a victim of furniture fashion—and by then, there was machinery that could cut a traditional-looking dovetail joint. While the curvilinear Knapp joint fit right in with the exuberant decorative excess of Eastlake and other late 19th-century furniture styles, as fashions changed from Victorian to Colonial revival, and to the exposed joinery of Arts and Crafts work, the Knapp joint was simply too visually inappropriate, so it fell out of favor.

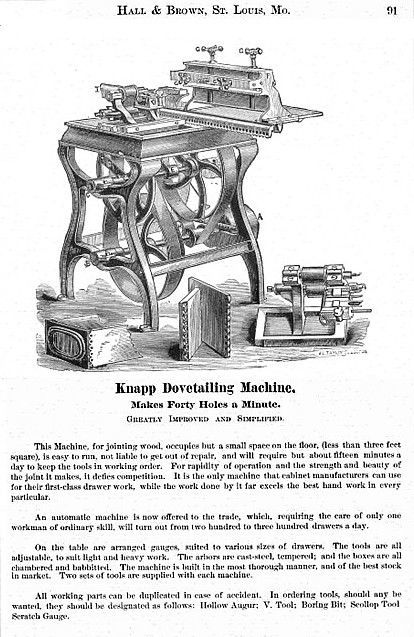

The sales copy reads, “This Machine, for jointing wood, occupies but a small space on the floor, (less than three feet square), is easy to run, not liable to get out of repair, and will require but about fifteen minutes a day to keep the tools in working order. For rapidity of operation and the strength and beauty of the joint it makes, it defies competition. It is the only machine that cabinet manufacturers can use for their first-class drawer work, while the work done by it far exceeds the best hand work in every particular.

“An automatic machine is now offered to the trade, which, requiring the care of only one workman of ordinary skill, will turn out from two hundred to three hundred drawers a day.

“On the table are arranged gauges, suited to various sizes of drawers. The tools are all adjustable, to suit light and heavy work. The arbors are cast-steel, tempered, and the boxes are all chambered and babbited. The machine is built in the most thorough manner, and of the best stock in the market. Two sets of tools are supplies with each machine.

“All working parts can be duplicated in case of accident. In ordering tools, should any be wanted, they should be designated as follows: Hollow Auger; V. Tool; Boring Bit; Scallop Tool Scratch Gauge.”

Read the Patents:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Freud Super Dado Saw Blade Set 8" x 5/8" Bore

Starrett 4" Double Square

Marking knife: Hock Double-Bevel Violin Knife, 3/4 in.

Comments

Cool stuff. Thank you, Megan!

Nice article Megan. I wonder if any of these machines are still kicking around?

CharleyRob, I looked high and low for a working machine – A video would have been great. But no joy.

— Megan

First, welcome to the FWW side of things. Second, this was an excellent description, and I hope you will keep more pieces like this coming. Thank you!

FYI,

Woodworkers supply has the bits to do this joint,it is called pin and crescent. The bits are to be used with a router, 1/4 or 1/2.

But all of this has to be used with their matchmaker™ joinery system, you supply the router.

regards Ralph McCoy

Nice article. I've missed Megan's "Editor's Note" at PW. She was probably finishing the home remodel. I've long wondered about origin of this joint, especially since it requires very exact machine work and is very labor intensive when done by a router or a drill press. There seems to have been a flood of inventors a century ago and they even applied their ingenuity to the lowly dovetail joint! Great research.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in