Consulting With Prospective Clients

“How do you handle inquiries from prospective customers?” asks a reader. “Do you have any rules for design and project approvals?"

Q: “How do you handle inquiries from prospective customers?” asks a reader. “Do you have any rules for design and project approvals? Do your drawings and color samples get signed and dated?”

A: Different woodworkers have different business models, not to mention varying degrees of interest in transparency. If you operate a full-custom business, as I do, each job requires a lot of input at the start. If you build to order, primarily from a portfolio of designs, your approach will likely be quite different.

I’ve learned to make the journey from first call or email to signed contract as streamlined and clear as possible, for my clients’ sake as well as my own. Here’s part one of how I roll.

Like many others, when I started my business I gave away a lot of time. I didn’t know any better. Those days were long before the internet and social media, which have made getting the word out so much easier and affordable; I simply needed income and didn’t have an established network of clients.

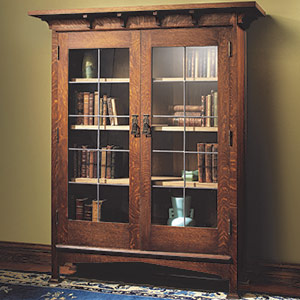

Someone would contact me about having a bookcase or entertainment center built. I met with them at their home (because most of my work is designed to complement its context) at no charge and with no strings attached, did scale drawings based on our discussion, and met with them again to go over the drawings and talk budget. Sometimes they asked if they could hold on to the drawings to think about them, and taking them at their word, I said yes. After hearing that a couple of these prospective clients had given my drawings to other cabinetmakers and had them build the jobs, I learned an important lesson.

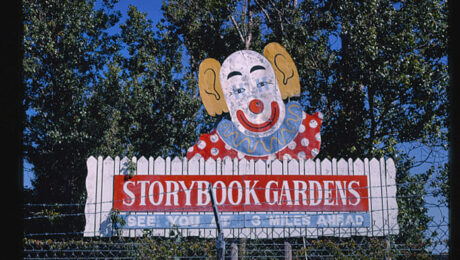

When I started my business, I intentionally included the word “design” in my business name as a way of notifying people of my interest in design—i.e., to discourage those who might want me to mill lumber for them or build bathroom magazine racks with integral toilet paper dispensers from contacting me. This implication of my business name made it easier to transition to charging for meetings and design work.

Step 1: Initial contact

When a prospective client gets in touch by email or phone, I explain how I work. We have a brief discussion focused on two questions:

- What are they looking for? I ask them to describe the job they have in mind.

- Can we work together? We need to figure out whether their ideas and my capabilities will mesh. Ideas and capabilities encompass not just my skills and the tools I have available, but also any budget they may have in mind and their desired timeline. If their budget is unrealistic and they’re unwilling or unable to increase it, we know we aren’t going to be able to work together. The same goes for schedule: If they want a new kitchen by mid-March and I’m booked until December, I can tell them so and avoid wasting anybody’s time.

Step 2: Preliminary consultation

Local clients

If the prospective clients are local, I will schedule a consultation that can last up to two hours. I charge for this meeting; my current preliminary consultation charge is the equivalent of two hours of shop time. Why charge for only two hours, when that won’t cover the time spent getting to and from the meeting? I’m trying to strike a balance between covering most of my time while not setting the price bar too high at the outset and scaring potential clients away. (It happens.)

During the consultation we discuss their ideas. I make suggestions, which range from aesthetic and functional considerations to specific materials they may want to check out. I also typically take measurements and will sometimes do some rough sketches in an effort to get us on the same page. Sometimes this is all a client wants from me; at other times it’s the start of a significant business relationship, and that’s the main point, for me: While the preliminary consultation leaves the client with substantial information and ideas, it also provides me a chance to sell my work.

Clients who are more than about an hour’s drive away

If the prospective clients are more than an hour’s drive away, I usually charge an hourly fee for travel.

Out-of-town clients

If they are in another city, I charge by the day so that I get paid for travel time as well as the consultation. Some may balk at the idea of charging for travel time; I did, early on. Then I reminded myself that the 5 hours I spend driving to the north side of Chicago would be billable if I were drawing a commission or working in the shop. In other words, the travel time is costing me big bucks if I don’t charge for it. If you can afford not to charge for this time and prefer not to do so, good on you. I have to charge for it.

I also make clear that prospective clients need to pay for travel expenses such as airline tickets and overnight accommodations. Typically, I’ll schedule my drive or flight to allow for a substantial meeting on the day I arrive, then a follow-up the next morning. This gives the clients some time to mull over what we’ve discussed the first day and we can build on those ideas over breakfast.

While this may sound like a big investment for potential clients to make for a preliminary consultation, I do my best to provide good value so that even if we don’t end up working further together, they have some solid information and new ideas they can use with another cabinetmaker. In reality, most distance jobs requiring onsite consultation at this stage involve built-ins, so I take detailed measurements and discuss various possibilities for the job, depending on the clients’ ideas—in other words, we would have to cover all of this anyway, so the visit allows me to streamline the process. And in most cases to date, the visit has resulted in good work.

Step 3: Design and consultation

If a client wants to proceed after the initial consultation, I write up a formal proposal for design work. “Design,” I always point out, will include further consultation (there’s a lot of back and forth with my jobs, because I like to work closely with clients), research into materials and related products, and drawings. I charge for all of this by the hour. My design proposal states the scope of design work, and when relevant, includes a note about the anticipated schedule so that clients can factor my timeline into their plans for other work. My design proposal also states deliverables, i.e. scale drawings, a list of products for a kitchen remodel, etc.

In cases where the design work is separate from the build—i.e., where there is no telling whether I will be the one hired to do the build part of the job—I charge for this work at a higher rate than for my shop time. I bring decades’-worth of experience and perspective to the table; I don’t want to feel as though I am in effect giving away my ideas to other builders.

Finish samples

Depending on the job, I may provide finish samples at this point or at the next stage, when the job is under contract. I make these up in the shop, taking the process all the way through from bare wood to top coats, to ensure the samples are representative. I keep records of exactly which products I have used, ratios in cases of mixed colors, etc., and the order in which I have applied them. This information goes in the client’s file along with everything else (and incidentally, it’s very helpful to have in case a client ever wants further pieces to match). I ask the client to let me know her choice of finish in writing, so I have a record.

Step 4: The build proposal

When the bulk of design work is complete (which is not to deny that changes may be made as the job progresses), I can provide a reasonably accurate estimate of what the job would cost to build. Depending on circumstances, I either send an email with a figure or range of anticipated charges, then wait to see whether it’s in the ball park, or I just go ahead and write a detailed proposal. Because my proposals include a lot of specifications, they take some time to write; this is why I often send a quick email with the price estimate first; if it’s way too high, I can often rework the specs to work with the client’s budget.

Next time: What’s in the proposal?

Nancy Hiller is a professional cabinetmaker who has operated NR Hiller Design, Inc. since 1995. Her most recent books are English Arts & Crafts Furniture and Making Things Work, both available at Nancy’s website.

More on FineWoodworking.com:

- Marketing for Woodworkers: Print Ads by Nancy R. Hiller, Darrell Peart

- Marketing for Woodworkers: Shows, festivals, and exhibitions by Nancy R. Hiller with Michael Fortune

- Nancy Hiller’s Reality Check(list) – If you’re thinking of turning your passion into a profession you should take a deep look at what is involved in running a legitimate business.

Comments

Great article!

Excellent info! I'm still a relatively new business, and don't do cabinetry, but this is very helpful to me. I've been struggling with coming up with a decent way to make these things work. I sell on Etsy, get local clients through my own website, and am working on a Shopify selling site. I've struggled with spending too much time before payment -- recently having spent about 6 hours on designing, researching, and communicating with a potential customer about a custom box...before having any payment to cover my time. It has been a learning experience. One of the main difficulties I have is that, because of my selling platforms, I have to essentially know upfront how much things will be, and how long it will take to discuss, plan, design, etc. I'm pretty good at estimating the actual build time, but design time is something I'm still figuring out. Perhaps I should start charging a consultation fee at the outset so that people know what to expect.

Thanks!

F*ck You, Pay Me -- Mike Monteiro

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jVkLVRt6c1U

I found this video mid-career as a graphic designer and it made me realize that I had been working for clients who undervalued me, and my work, for years. Mike's advice can be applied to anyone in a creative field.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in