The Bad and the Beautiful of Period Apprenticeships

It is easy for us to conjure up visions of period apprenticeship that are heavily romanticized, but in reality, each shop was a working business where making the next shilling superseded the need for the apprentice’s next lesson

Sometimes things do change for the better. We just hired two new apprentices at the Hay Shop at Colonial Williamsburg—they are not kids between the ages of 14 and 16, they do not work 72 hours a week for no wage, and they don’t sleep on my attic floor. Those were typical—and legal—apprenticeship conditions in the 18th century. It is easy for us to conjure up visions of period apprenticeship that are heavily romanticized: a young man peers over the shoulder of a caring master craftsmen who patiently reveals the art and mystery of his trade to the next generation while basking in golden, afternoon sunlight. While I’m sure this kind of scene did play out many times, it’s just as likely that the shop was dark, the master was a bumbling jerk, and the apprentice’s adolescent gaze was fixed on the neighbor girl across the way.

In reality, each shop was not its own little North Bennet Street School, but rather a working business where making the next shilling superseded the need for the apprentice’s next lesson. The apprentice, then, was as much a source of cheap labor as a student. But this was explicitly the deal that was commonly laid out in the apprentice’s formal indenture (contract). Like with indentured servitude, the apprenticeship needed to be mutually beneficial to all parties concerned. Many indentures survive in records and most list a series of promises the young man or woman made to the master or mistress and vice versa. Typically, a master was responsible for teaching all branches of the trade, rounding out the apprentice’s education (reading, writing, basic arithmetic), providing room and board, clothing, and a proper moral upbringing. The apprentice, in addition to pledging obedience, promised to not do a long list of things like divulge the master’s secrets, frequent the ale houses, marry, gamble, fornicate, and all the other things that occupy the mind of your average 19-year-old. This agreement was usually binding for a period of five to seven years, though the length varied widely for many reasons.

Considering how ubiquitous the apprenticeship system was in the 18th century, it is surprising that we know very little of what the daily life of an apprentice was actually like. But, then as now, mundane events often go unrecorded. While there are a few period writings that cover the general nature of apprenticeship, most of what we know comes from small clues embedded within descriptions of exceptional circumstances. Newspaper notices for runaway apprentices, court records of formal complaints leveled at masters by mistreated apprentices, personal journals, and artifacts all help fill in the details. Below are three of my favorite snapshots of 18th-century apprenticeship. Each is exceptional in some regards, but also typical in others.

The Bad Master

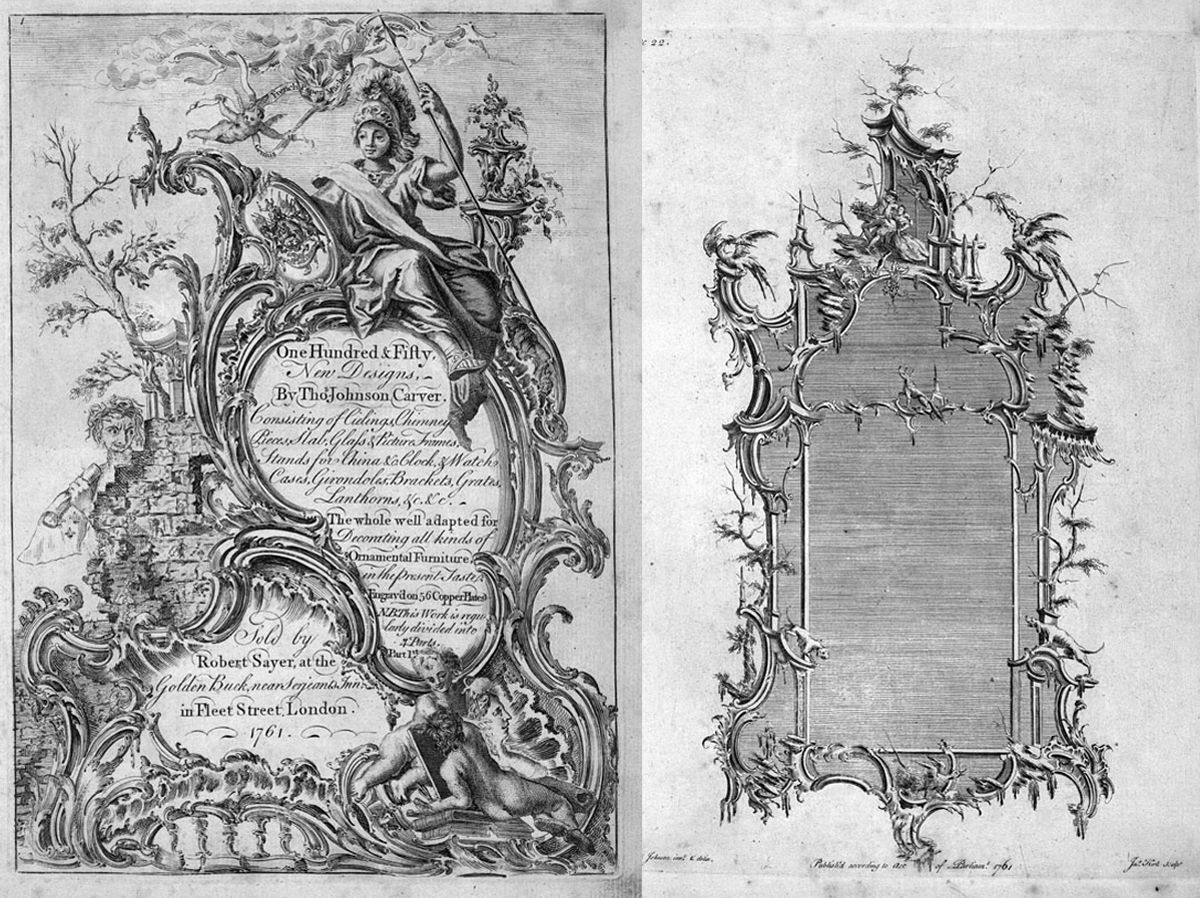

Thomas Johnson (1723-99), whose work is pictured above, became one of Britain’s leading designers and carvers despite serving an apprenticeship under a master whom he described as “the worst carver I ever saw that had any title to the profession.” Unlike the vast majority of 18th-century craftspeople, Johnson left behind an autobiography—itself only discovered within the present century (published in the journal Furniture History, Vol. 39 [2003], pp. 1-64). Though he did not use the text to describe the daily life of an apprentice carver, Johnson gives some clues to the inadequacy of his training. Other English and American documentary sources show that many masters offered only as much training as was necessary to turn the apprentice into a semi-skilled source of cheap labor. Such a strategy had short-term benefits to masters, but limited the apprentice’s prospects for successful future employment. Johnson, feeling this anxiety in the final year of his term, recounted a rebellious confrontation with his master:

“I told my master he did not do me justice, having served six years, and no opportunity of learning more than I knew the first six months, and if he did not procure some means for my improvement, I would run away, and go to France: upon this he struck me, and though I had often felt his blows before, I was now pre-determined, if he struck to strike again. Provoked at the blow, which was a pretty hard one I returned it in his face, the receipt of which made his nose bleed: unfortunately for me a hair broom standing near, my mistress broke my head with it; upon this, my fellow apprentice knocked her down with his fist: her brother being in the house joined the fray, and a battle royal ensued. The shop being on the ground floor we soon got out and run off, and our master after us…”

After three days, Johnson returned and reportedly finished out his indenture in peace and on good terms. His first paying job (at a low wage that reflected his training) was in a large London carving shop where Matthias Lock (one of England’s finest carvers and designers) was also employed. Fortunately for Johnson, Lock took him under his wing, seeing to it that his skills matched his natural ability rather than his initial training.

The Bad Apprentice

Not all apprentices who ran away came back or were much missed. Colonial newspapers are filled with ads for runaway apprentices. Bad masters, teenage temperaments, the promise of something better, along with any number of other reasons might cause an apprentice to break the legally binding indenture and run off. When this happened, masters often placed ads in local papers that described the runaway’s demeanor, dress, property, and so forth. Occasionally, the ads also offer a little glimpse into the nature of the student-teacher relationship.

One of the more colorful examples from 18th-century Williamsburg was placed by carpenter James Gardner in the Virginia Gazette in 1773.

“Run away from the subscriber, in Williamsburg, on Saturday the 13th instant (March) William Bolton and Charles Winfree Chandler: Bolton is about 18 years of age 5 feet 6 inches high, very clumsy, and has a sour countenance. Chandler is about the height of Bolton, 17 years of age, and has an agreeable countenance. Whoever conveys Chandler to me shall receive TWENTY SHILLINGS, and I hereby offer a reward of ONE HANDFUL of SHAVINGS to any person that will secure Bolton so that I may get him again.

James Gardner

N.B. They took with them a couple of two feet rules, which all persons are forewarned from purchasing, as also from harbouring or employing them. If Chandler will return of his own accord, I hereby promise not to give him the least correction.”

A handful of shavings! One wonders what Bolton could have done to earn such a pre-Twitter public shaming from his master. Nonetheless, ads of this nature were fairly common during the period and prove to be one of the best—though fraught—sources of information on apprenticeship.

When Things Go Right

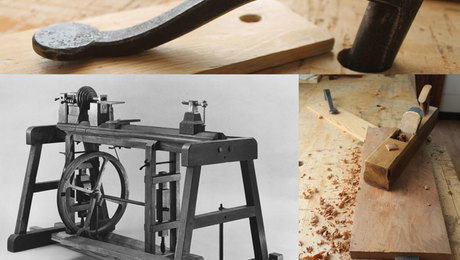

Sometimes apprenticeships didn’t end with a fist to the face or a fistful of shavings. Sometimes it was a chest full of tools and a promising future. Such was likely the case when English cabinetmaker Benjamin Seaton concluded his apprenticeship under his father, Joseph, in 1796. Because fathers and sons did not need formal indentures, the dates and details of young Seaton’s apprenticeship went unrecorded. His training likely concluded when he reached age 21 (a typical ending point for young men) in 1796. By December of that year his father had purchased him an extensive kit of cabinetmaker’s tools. On January 1st of 1797 Benjamin, now a journeyman, set to work on constructing a chest to house this generous gift. By April 15th, the chest, neatly executed and decorated with veneers of mahogany and tulip wood, was complete (a faithful replica of Seaton’s chest made by my former Hay Shop colleague Kaare Loftheim is pictured above). Clearly, Joseph had also given his son time and materials to make the chest in addition to the tools to fill it. While many indentures listed a sum of money—known as freedom dues—or goods worth that amount (typically a few tools and clothing) to be paid by the master at the end of the term, Benjamin seems to have hit the jackpot!

If you’re unfamiliar with this remarkable chest and its tools (they’re still together in the Guild Hall Museum in Rochester, England), its story is told in great detail by Jane and Mark Rees in their book on the subject (required reading for period furniture makers). Oddly, our knowledge of Benjamin Seaton’s cabinetmaking career lies solely within the tool chest. There are no other extant pieces that can be attributed to his hand and, most mysteriously, the tools in the chest appear to have been used very little. Benjamin likely took on a managerial role within his father’s business, but the details of his life, like those of so many who apprenticed in the woodworking trades, remain just beyond our reach.

Comments

Excellent! Thank you for that glimpse of history. Well done!

Great article. It would be lovely to see that beautiful chest presented more clearly, and even offered as a project - quite a different proposition from the North Bennet St Box...

Awesome article, love history pieces. Thanks for writing it.

Quite an enjoyable read and insight. Thank you.

Thanks for those stories. Insightful on both master and apprentice levels. A bit humorous as well 😂

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in