Waste knot, want knot

There’s a sentiment most woodworkers take to heart—for some, it’s good advice to follow whenever possible while for others it’s an unbreakable rule. Then there are those who seem to ignore the idea altogether.

Avoid wood with knots. There’s a sentiment most woodworkers take to heart—for some, it’s good advice to follow whenever possible while for others it’s an unbreakable rule. Then there are those who seemingly ignore the idea altogether. When I lived in Texas, I used to see people selling knotty pine furniture out of trucks parked along busy highways; these are the folks I’m talking about. Surprisingly, I would add many 18th-century craftsmen to the ranks of makers with little fear of knots. I’m talking about the kinds of makers whose work now sits atop pedestals in many celebrated museum collections. These makers did not go out of their way to choose knotty materials, but they didn’t work overtime to avoid them either.

Currently in the Hay Shop, we’re reproducing an antique high chest of drawers from the Colonial Williamsburg collection (CWF 1973-325) that contains a great sampling of the good, the bad, and the downright ugly of the kinds of knots that I see regularly on period pieces. Made in or around Winchester, Va., in the mid 1790s, the high chest has many remarkable features – its rear claw-footed cabriole legs do face forward after all – but for the purposes of this discussion, let’s focus on its knots. (If you want to learn a lot more about this piece, please join us in Williamsburg this January for our annual Working Wood in the 18th Century conference.) To my mind, there are four circumstances in which knots show up on this piece. Let’s consider them in turn from the most innocuous to the most problematic.

Out of sight, out of mind

As seen on countless period pieces, there are plenty of knots hidden away on secondary surfaces, like backboards, interior drawer parts, dust boards, and so forth. Of all of the knots found in period work, these are likely the most palatable to today’s furniture maker. They make good economic sense; why waste wood when you can bury these boards on the inside and still expect them to serve their structural purposes? Sure, they can be a little squirrely to work by hand, but with a sharp blade and a smart angle of attack, they’ll plane up cleanly and if they don’t, well, who will notice? In the image on the left, the knot is sound and unlikely to create stresses that would cause this backboard to fail. It’s also a backboard on a chest of drawers, so nobody ever sees it. The knot pictured at the right is a little more of a gamble. While still hidden from view, this time on the top of a drawer blade, the tension in the grain around it has the potential to distort the board and throw off the fit of the drawers above and below. After 230 years, it’s safe to say that the gamble paid off, though I’m not sure I’d press my luck and try it myself. The tearout around that last knot is neither a problem nor a surprise, but it would be a problem in this next category of knots.

Knots in the middle of flat primary surfaces

In this category I include knots on surfaces like drawer fronts, case sides, and door panels that are visually noticeable, but don’t present major structural challenges. Very small, tight knots here or there are never really a problem, but some period makers placed large knots in very prominent places. The maker of this high chest seemed to have no issue with showing off a juicy knot or two. On the upper case of the chest, in the center of the center drawer, there is a prominent knot that, though planed very cleanly, has developed a cross-shaped crack through its center.

The crack is basically an “X-marks-the-spot” pointing to the dead center of the upper case drawers. Maybe this is haphazard – the maker using the available wood in some random fashion – but I don’t think so. I believe that knot was placed there intentionally in an effort to best use the available materials. While prominently displayed, the knot does help create a deliberately balanced look to the drawers. If it were off to one side or the other, the knot would look disruptive. Despite its eventual cracking, the knot never really compromised the drawer’s structure. A much more dubious knot usage from the same shop that produced the high chest is seen on the writing surface of a desk and bookcase in the Colonial Williamsburg collection (CWF 1930-68). The photos below show that they certainly tried to make this one work, but you can judge their success for yourself.

Why would you do this to yourself

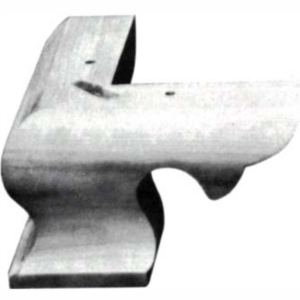

As every woodworker knows, knots are difficult to work by hand and machine. While the knots in the last category were likely used out of economic necessity, they weren’t too difficult to handle with sharp tools. The knots in this next category though, fall in prominent places that get worked extensively with various tools. These might begin to create structural problems, but they mainly represent serious challenges to the worker. Such “why would you do this to yourself” moments in material selection always fascinate me. There is likely some unknown, though familiar story lurking behind the decision to create complex shapes through knots. The high chest has one of these on the left front leg post right where it meets the quarter column.

The knot makes it abundantly clear that the quarter column is integral to the post and not an appliqué (the column’s capital is applied). What prevented the makers from placing this leg stock elsewhere in the piece or re-orienting it so as to avoid carving a fluted column through a knot? In other words, why did they do this to themselves? Perhaps another orientation would have led to serious structural problems – maybe they deemed the knot better on the decorative outside than in the midst of the mortise and tenon joinery on the inside corner. Regardless, if you look closely at enough period pieces you’ll begin to see masochistic things like this more often than you might have expected.

Mistake knots

The last category of knots on period work like the high chest can most accurately be described as mistakes. These are knots in very vulnerable structural positions. I imagine their placement arose more from necessity and a hope for the best rather than thoughtlessness. No matter; they don’t work, as time and conservators can attest. The massive size of the high chest’s upper case would tax the strength of any cabriole leg, but a leg with a massive knot right through its slender ankle is most likely going to fail. The picture below of one of this piece’s rear legs requires no further explanation.

I did not write any of this to denigrate 18th-century work, but simply to call attention to a difference between what they made and the work of many of the finest furniture makers today. Knots are easy to overlook in glossy museum catalogs, but harder to miss when you are standing in front of a piece in person. The 18th-century world was very different than ours. Materials like fine-grained hardwoods often accounted for a much higher percentage of furniture’s final cost compared to today. Likewise, period labor rates were relatively cheap. When seen from this perspective, it makes sense that early American makers used every bit of wood available and worried less about the extra labor in dealing with a knot or two. In many ways though, our world is a lot like theirs. No matter how high labor costs are, wood is still not cheap and now its abundance is threatened. We will do well to consider their frugality with material. Pieces like this high chest can teach us a lot. Where knots are concerned, it provides some pretty good lessons about what and what not to do.

-There is still time to get tickets to the 22nd Annual Working Wood in the 18th Century Conference, to be held January 16-19, 2020, at the Williamsburg Lodge in Williamsburg, Virginia. This year’s topic is: Down the Great Wagon Road: Furnishing the Southern Backcountry.

|

Learn From Antiquesby Steve Latta |

|

|

|

Measuring a period pieceby Bill Pavlak |

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Ridgid R4331 Planer

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

DeWalt 735X Planer

Comments

I enjoyed this blog. When you mill logs into lumber by hand, you want to use everything you have spent time and effort preparing. Milling wood by hand may not be as fast or efficient as with machinery, but it's a great cardiovascular workout. Stretching your wrists before, during and after can help prevent carpal tunnel and tennis elbow or at least help you recover from it. Machinists whine about blisters and sore muscles, but you can build up your endurance and develop callouses. The only thing is the time factor and production work that professionals need to satisfy the customers and earn a living.

I try to be conservative with the wood I have. After selectively getting what I can from the lumber yard, I work with what I have and try not to be too wasteful and put knots where they won't be as visible or are symmetrical. Not obsessive about it easier.

Having said that, some of my favorite little spots on each piece of furniture are the smaller size knows. After they are smoothed and finished (shellac then wax for me), they look very nice.

As a decades long woodworker, I have used many different kinds of wood, including salvage. A few years ago I built my kitchen cabinets entirely from re-used materials, much of which would have been burned or ended up in a landfill. I call them my "junk" cabinets. But they do not look like junk. They look like (& are) fine custom cabinets. I used American Chestnut from an old tree that blew down in Northern Ca. I purposely picked through it to find material with the most radical grain & knots. I knew I was causing myself more work, but chose to put myself through the grief to get the interesting look I wanted. They are Beautiful & have gotten a lot of compliments.. Ooohs & Awwws.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in