An artist masters the craft of furniture making

From Home Furniture Issue #3 - Duane Paluska builds furniture that speaks with the unassuming eloquence of its maker

We were very sad to hear that Duane Paluska died today. A brilliant, bookish man and a wonderful furnituremaker and sculptor, he lived in Bath, Maine, with his wife, Ellen Golden, in a house he built. He also built all the furniture in it. He was the director of Icon, a painting and sculpture gallery situated in an old house in downtown Brunswick, Maine. His workshop was in an attached wing, and most days he shuttled multiple times between his small office in the gallery and his workbench. I met him in 1994, when Home Furniture magazine had just been launched, and I wrote this profile of him in the third issue. He made an enormous impact on me, and very few weeks have gone by since without my thinking of him.

-Jonathan Binzen

An Artist Masters the Craft of Furniture Making

Duane Paluska builds furniture that speaks

with the unassuming eloquence of its maker

In Duane Paluska’s workshop in Brunswick, Maine, there is a collection of old industrial woodworking machines and a plain, sturdy bench where Paluska makes both furniture and fine art. On the bench and on shelves nearby, planes and drill bits fight for space with brushes and paints. A short hallway joins the shop to the back of a two-story building that houses an art gallery where paintings and photographs by local artists hang. The link is convenient because Paluska is the proprietor of the gallery as well as the workshop. Push a bell in the gallery, and Paluska will emerge from the shop —speckled with sawdust or smudged with paint.

Many furniture makers trip on the line between furniture and fine art. In the 20 years since he left the English professorship that brought him to Maine, and he began making a living with his hands, Paluska has learned how to cross that line without mishap. His furniture, supremely functional but filled with nuances of texture, color and shape, reveals the eye of an artist but contains none of the imagery of art; his art, painted, three-dimensional pieces he calls “wall reliefs,” shows the refined hand of a craftsman but eschews the functions and forms of furniture. The strength this symbiosis gives his furniture is most evident in the house he built and filled with his furniture, where all but three of the photos for this article were taken.

Download the original article in Home Furniture #3–1995

Building patiently on the past

While furniture and fine art aim in different directions, Paluska says that, to succeed, both must incorporate the spirit of their maker. Yet, with furniture, too much spirit can be damaging, he feels. Innovations ought to be slight and should come slowly. He observes that many of today’s studio furniture makers “have taken a page out of contemporary fine arts—they want something striking and original, something novel. But good furniture doesn’t require earthshaking originality. The best furniture results from a slow, step-by-step process of modifying something that you and others have done before.”

The slow evolution of Paluska’s own furniture is most easily

traced in his chairs. When he began making furniture for a living, he made chairs closely based on American country versions of Chippendale and Queen Anne chairs—sturdy, functional and handsome. His versions of those old chairs grew more stylized and contemporary over the years until they became recognizably Paluska’s own.

The growth didn’t end there, however. The slightly mismatched chairs around his dining table are evidence of his use of the same forms again and again (see photo above). With each run of chairs, he makes refinements. His earlier chairs, for instance, were flat on both sides of the back. Now Paluska leaves the front surfaces flat, but he subtly rounds, relieves and chamfers the rear surfaces to make the chairs more interesting to see from all angles and more inviting to touch. What keeps him making refinements is the dream that out there somewhere

is the perfect chair. “But of course,” he says, “I’ll never reach it.”

The basic leg and back structure of the country chairs still underlies Paluska’s current chairs, but the stronger heritage is in the attributes those early chairmakers taught him to strive for in his work: “Simplicity, clarity and understatement; usefulness, strength and elegance.” It’s a tall order, but one Paluska’s work regularly fills.

An artist’s case against drawing

If you ask to see the finely rendered drawings Paluska makes before building a piece of furniture, he won’t oblige. He can’t. I expected that Paluska, being an artist, would lean on drawings to develop his designs. But he does very little drawing as a furniture maker. In his woodworking, as in his art, he develops the piece as he works. He thinks that by leaving details unresolved at the start, they become more a part of the piece, growing right out of the building process. “I find this a much more interesting way of doing things,” he says. “I admire an architect’s ability to design something entirely on paper, but for me, having everything settled from the start would make the construction dull. The disadvantage, of course, is that you can blunder. But I like the constant engagement of my imagination that working this way requires. I’d have a hard time maintaining interest otherwise.”

Paluska also jumps right into the construction because he believes that drawings and models, by miniaturizing an object, make it look too cute and make it hard to sort out the ungainly from the graceful. He also feels that trying to render on paper something as complex as a chair is futile. “Seeing a chair in front, side and back elevations just won’t show you what it will look like. That’s not how chairs are perceived.” With simpler, rectilinear work such as case pieces, though, he feels a drawing can be useful.

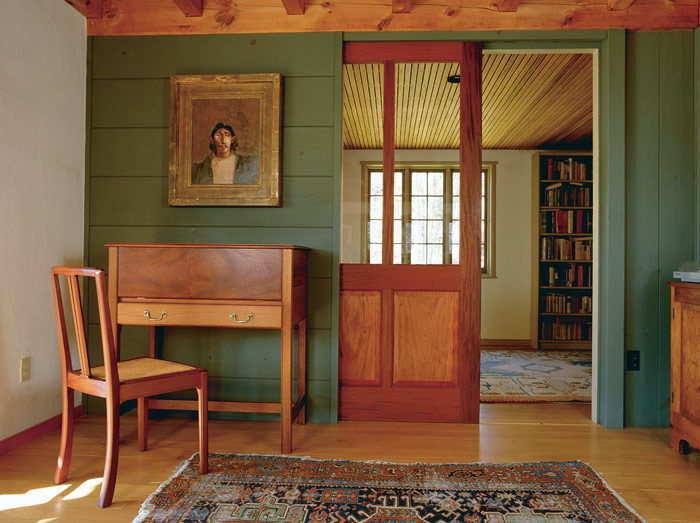

The well-composed house

Paluska spends about half his time making custom furniture and the rest tending his gallery, making art and working around his house and property. Paluska built the house and nearly all the furniture in it. Here his facility for selecting and combining materials, textures and levels of craftsmanship is demonstrated in every room.

He was inspired by turn-of-the-century houses of California architects and furniture designers Charles and Henry Greene, among others, but the feeling in his house couldn’t be farther from the feeling inside the Greenes’ Gamble House. The Greenes built their extraordinary Arts and Crafts bungalows like giant pieces of furniture: Architectural details were taken to the level of furniture. Even in the garage of the Gamble House, the woodworking is magnificent. The furnishings and the house are one organism; you can barely tell where one leaves off and the other begins.

In Paluska’s case, the house is still a house. It is a container for the furniture. And the furniture, rather than all being exquisitely detailed and lovingly burnished, is designed to fit a niche, to carry a certain weight, to perform a specific function and to express that function. In his house, each piece of furniture, each door, each wall, is part of the whole composition. And like any good artist, he knows that composition requires contrast; if all lines are the same weight or all surfaces the same color or texture, the composition loses its power.

As you walk through Paluska’s house, things constantly make you feel good. After passing through the entry hall, I had a stray sensation of pleasure. I’d examined the entry before: the fine cabinet in the style of James Krenov on a plain wall of beaded pine planks, the sensuous banister made without spindles to keep the small entry from feeling cramped, the closet door with its panel of vertical slats adding an unexpected touch of texture. But there must have been something that previously escaped my notice. I walked back through and looked around. It was the bathroom door. A simple, painted frame-and-panel door. What had registered was the variation. Instead of having three panels like the bedroom doors upstairs, it had four, and the medial stiles in the upper panel were splayed slightly in a tall V shape. Although on first glance they appeared alike, I found that no two doors in the house were the same.

A reticent man makes a modest living

Paluska enjoyed teaching, but after five years at Bowdoin College, he was spending as much time making furniture as he was teaching English and decided he preferred furniture making. Then, as now, he got commissions strictly by word of mouth. And in the years since he left Bowdoin, he’s never been short of work.

“Earning a modest living hasn’t been a problem. I’ve always had six months to a year of work ahead of me. As far as stability goes, I’ve got it all over General Motors, where people work week to week.” He’s managed this stability without ever advertising. Selling himself doesn’t come naturally, and he hasn’t tried to learn. “In a certain way,” he says, “the ideal would be if I never actually had to meet any clients. I’d just like to make things and then hear second-hand that they were appreciated and useful.”

Paluska’s friends probably would describe him the way he describes the ideal chair: “one that quietly does its job, that does not call attention to itself but rewards the scrutiny of a person who chooses to give it a close look.” ν

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in