George Wurtzel sees things differently

If you want to pay George a compliment, he’d rather you didn’t use words like “amazing” or “inspiring.” Good luck avoiding them.

If you want to pay George Wurtzel a compliment, he’d rather you didn’t use words like “amazing” or “inspiring.” Good luck avoiding them.

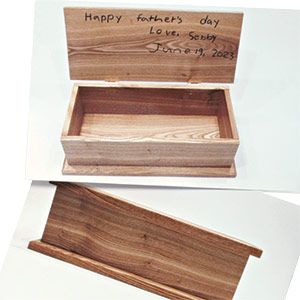

Born with a genetic eye disease that left him completely blind in his 20s, Wurtzel has been a full-time cabinetmaker, countertop builder, and fine furniture maker ever since. Along the way, he ran a large millwork shop and designed a triangular burial box for veterans’ flags, more than a million of which were sold by the company that bought his patented design.

Now in his 60s, he is rolling out a new line of Craftsman-style furniture that fits together like a puzzle, without fasteners or glue, designed to be disassembled easily for shipping or moving.

What Wurtzel wants to be called is a skilled woodworker, and what he wants you to see is his work. What you’ll find is a beautiful variety of soulful work, from architectural millwork to kitchen cabinets, lamps, puzzles, furniture, and handcrafted home decor. You’ll also find the piano-shaped coffee table Wurtzel made for Stevie Wonder and the seaworthy sailboat he built for Maire Kent, who visited with him before she died to commission a vessel for carrying her ashes from Lake Michigan to the Atlantic ocean. The whole story is captured in a documentary, called “Maire’s Journey,” and a lovely preview is available on YouTube.

How a blind woodworker navigates the shop

If Wurtzel wants to cut something out on the bandsaw, he makes a cardboard pattern and uses a locator pin on the table to follow it. “It’s not efficient but it gets the job done,” he said. As a fellow woodworker I was amazed and inspired (sorry, George) by the work on Wurtzel’s website, and I had some practical questions. “Are there any machines or tools you don’t use?” I began.

“No,” he said. “There is almost nothing I do differently other than the ruler I use,” referring to the Click Rule, which measures in 16ths with audible clicks and is a boon to sight-impaired artisans and crafters. It’s available at Highland Woodworking. On Highland’s free web TV show, you’ll also find an excellent episode on Wurtzel.

“Walk up to a tablesaw and think about the steps required to cut wood,” he suggested. The fence is fixed, the blade is spinning in place, the only thing that moves is your hands. When I need a push stick, I run it against the fence.”

As we spoke, I closed my eyes and went through the steps I would take on various machines if my shop were dark, and I started to get it. Still, I was amazed, and inspired. (Sorry, George.)

As for telling woods apart in the lumber stack, Wurtzel uses a combination of touch, smell, and even taste. Touch reveals pore structure. Temperature matters too, with soft woods like pine warming instantly to the touch and hard maple, for example, staying cool longer. Wurtzel draws the wood closer and smells it. And for a few of the trickiest species, he tears off a splinter and tastes it; turns out some woods are sweet and others bitter.

To check grain direction, he sprays the surface with Windex, which raises the grain long enough for him to feel it, before flashing off quickly. To combine woods in a design, he refers to the mental catalog of looks and colors he built up in his teens and twenties.

Passing it on

These early decades were pivotal in many ways. In his teens, Wurtzel attended the Michigan School for the Blind, where he learned the “soft skills” needed to get through the day and also the technical skills he needed to work wood. “One of my idols was a totally blind guy we called Mr. R., who taught industrial arts,” he said. “There was no piece of machinery he couldn’t run or fix. He taught me how to carve wooden chains, and the little ball in the cage. You name it the man could do it.”

That description of Mr. R. sounds a whole lot like Mr. W., who is inspiring a new generation of people. In fact, you might already know him. Wurtzel starred in a Subaru commercial called “See the World,” where he takes a young couple on a road trip to his favorite places, helping them see and feel them the way he does. It was one of the manufacturer’s most popular TV ads of all time, and ran for a total of 18 months. It also netted Wurtzel an unexpected windfall of residuals, enough to buy an old industrial building in Greeneville, Tenn., where he plans to live and work in retirement, making exactly what he wants to.

Dream shop in Tennessee

“My dream when I was 19 was to own a building that was big enough to house a woodworking shop, a place to live, and a showroom,” Wurtzel said. To make that happen, Wurtzel and his longtime partner, Sharon Burton, took a long road trip through Tennessee, where she has family, stopping at any “beat up, run down, decrepit place that had some architectural detail intact,” she said. “If there was an empty building with a great doorway and a for-sale sign, George would look it over.”

They found their new home in the historic district of Greeneville, which enjoys steady tourist traffic and a mild climate. The old laundry and dry-cleaning building—6,000 square feet on 2 floors—was a mess, George and Sharon said, with rainwater pouring through the roof and cascading past the electrical panel.

|

|

Wurtzel and his longtime partner, Sharon Burton, converted this rundown building in Greeneville, TN (left), to a studio and workshop (right).

“George had to put his shoulder to the door to get it open, and then he kept talking about all the things he liked,” Sharon said.

“You’d have to be blind to understand the potential,” George said with a laugh. “It needs work, but it’s work I can do. It has a wonderful space for a workshop to work and teach in, and a large gallery space plus room for a nice apartment with a guest room.”

The first thing he did, with the help of visiting friends, was to build a nice bathroom. Next they turned the room at the front of the store into a showroom so George could house the work he brought from California. The space will serve as the retail outlet until a larger gallery is finished in late 2020.

Calling themselves “urban pioneers,” the couple made the old breakroom their bedroom and the large steaming and pressing space their living room and kitchen. Installing windows and gas heaters made the place livable.

Once moved in, George renovated the big basement level for his workshop, bringing in most of his machines and adding a string of Christmas lights so Sharon could find her way around. Then Sharon wrote and received a grant from Greeneville’s Main Street program to restore the front facade.

A woodworker’s tribute to Helen Keller

Most recently, George got approval from The American Foundation for the Blind to launch his most ambitious and meaningful project ever, 100 reproductions of an Arts and Crafts-style desk used by Helen Keller, funded by her many modern admirers. What’s really special is how the desks will be built, by blind and deaf artisans, who will travel two and three at a time to work with George in his new workshop in Greeneville. The foundation will provide access to the Keller archives, and their list of generous donors and followers. And in the end, funds raised by the sale of the desks will go in part to create a fellowship for blind and deaf-blind people to study manual crafts of all kinds.

“Helen Keller paved the way for me to do what I do in my life as a blind person,” George said. “Who would have thought a deaf and blind person would have risen to her status, especially considering how people with disabilities were looked at 100 years ago—when so many were institutionalized. She traveled the world when most people didn’t leave their own counties, and created an international platform to show the world that people with deafness and blindness could be productive, contributing members of our society.”

As their old building and their new life take shape, George and Sharon are recruiting other artist friends to join them in Greeneville. “There are lots of other affordable buildings like ours,” Sharon says. It’s a tempting offer.

|

These Blind Woodturners Are An Inspirationby Betsy Engel |

|

|

|

Comments

Just looking at the pictures scared me. The long beard and the hat with the beaded string hanging down near the lathe are just invitations for a broken neck when something gets caught in the spinning machinery. Sad to see this being promoted through articles in this magazine. A 22 year old Yale graduate died in a lathe accident in 2011 when her hair pulled her into the machine.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in