Adventures in Woodworking–Fernan banks on ammonia

From issue #14, George Frank tells a dramatic story of wood finishing failure and salvation.

Originally published Fine Woodworking issue #14:

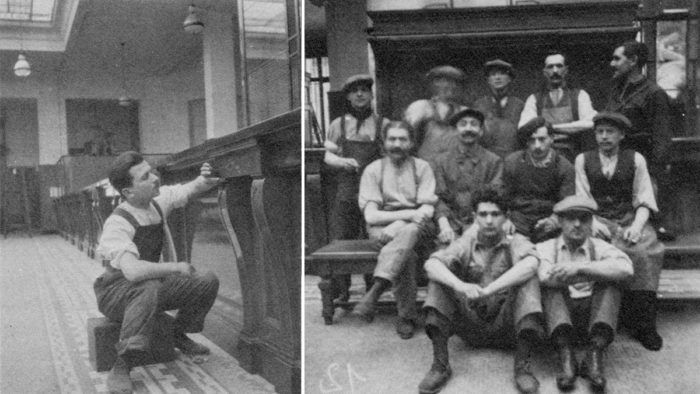

Since no one could pronounce his name-Ferdinand Schnitzspanhis customers simply called him Fernan. We, his workers, addressed him as “Patron.” He was a giant Alsatian and in the early 1920s he ran a good-sized wood-finishing shop in Paris. All his men liked him; I, then a youngster of 21 , loved him like a father.

This was the time when France was rebuilding after World War I , and the Banque de France was Fernan’ s best customer. New branch offices were being built and opened up in every important town. The furnishings of these banks were made in Paris, and Fernan had the contract to finish them. The style was always the same, and the wood was invariably oak . The only allowed difference was in the finish , or more exactly, in the staining. The architect could select one of four colors, ranging from No . I, the lightest, to No. 4 , the darkest. Early in June we shipped out all the woodwork for a bank to be installed at Lisieux , a town closer to Deauville than to Paris. This branch was supposed to open up on July 16 , just after the Bastille Day holiday.

Around July 10 there was a big upheaval in our shop. The telephone did not stop ringing, telegrams arrived, people were coming and going like chickens without heads, and all of us sensed that something was amiss. By noon the secret was out-the Lisieux bank was stained too light. Fernan had made an error. His order had called for color No . 3 , but he made us use No. 2 , a lighter one. The architect was adamant: He wanted the color he had specified and told Fernan in no uncertain terms to come and darken up the bank before the opening date .

Around July 10 there was a big upheaval in our shop. The telephone did not stop ringing, telegrams arrived, people were coming and going like chickens without heads, and all of us sensed that something was amiss. By noon the secret was out-the Lisieux bank was stained too light. Fernan had made an error. His order had called for color No . 3 , but he made us use No. 2 , a lighter one. The architect was adamant: He wanted the color he had specified and told Fernan in no uncertain terms to come and darken up the bank before the opening date .

Fernan had a car built to carry four people, but the next morning he and six of his best men somehow squeezed into it, along with all the material needed, and headed for Lisieux. We arrived around 9 a.m. and entered the bank. There was no question about the error nor about the size of the task on our hands. Even if we worked 24 hours a day , it would still take 10 to 15 days to restain and refinish the bank. After hashing over every possibility, Fernan and his men decided that the situation was hopeless-the job simply could not be done in the remaining few days.

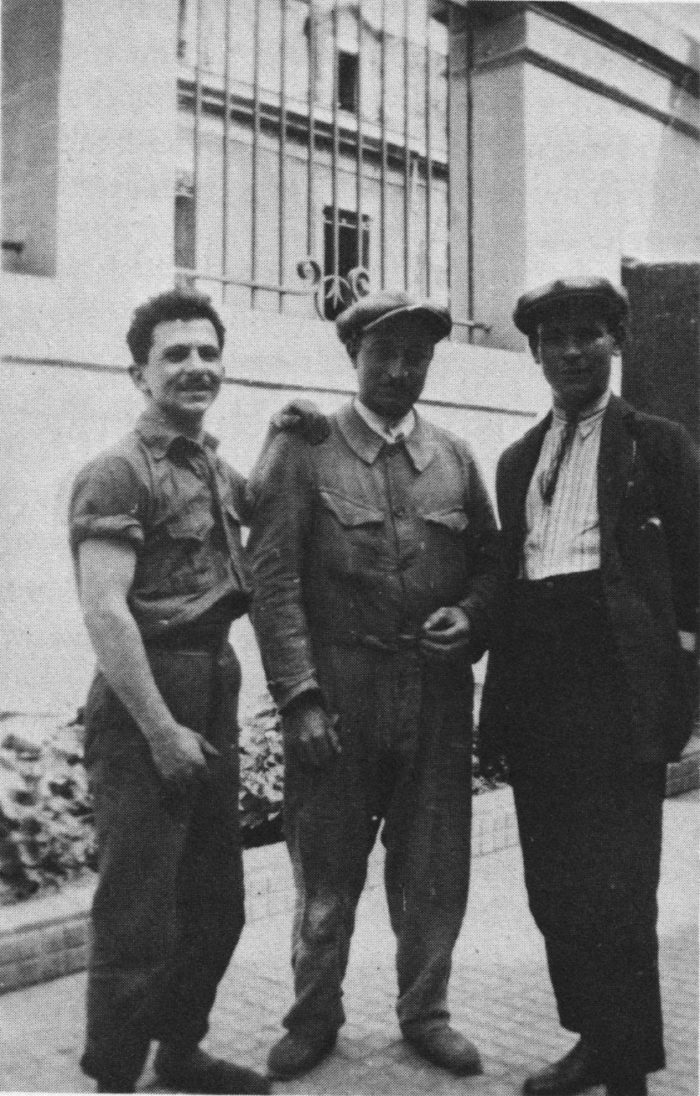

There was one fellow who did not open his mouth, me, but whose mind was working furiously. Although I was the youngest and the least experienced member of the group, I had had more school learning than the other six combined. In evening courses I had studied wood finishing for two years. Now, when doom settled on our small company, I touched Fernan’s sleeve and very timidly said, ” Patron, I think I can do the job by tomorrow night . . . ” Six pairs of eyes looked at me, not knowing whether I was joking, dreaming or trying to be funny. I explained that the job could be done by gas. If we could create a strong enough concentration of ammonia gas in the bank, there was a great chance that it would go through the thin layer of finish and react with the tannic acid in the oak to darken the wood.

Since there was no other choice, my plan was accepted. We sealed all doors, windows and openings. Then we made about 30 simple alcohol burners, consisting of a board about 10 in. square, with a small bowl containing about a half pint of alcohol in the center. Three long nails held up a small pail over the bowl. With wet towels over our faces, we poured the strongest ammonia we could find into the pails, lit the alcohol and scurried out of the bank, leaving all the lights on and closing and taping up the last doors. By the time the alcohol had burned out, all the ammonia had evaporated, and there was such a concentration of gas in the room that no living thing could remain. Then we went to sleep.

Sleep, no one could. We played cards and drank an awful lot of Calvados, a local apple brandy. Every hour we checked whether the gas was working. It was not, at least not fast enough for us to see. But the next afternoon the architect joined our group with a sample in his hands. Peeking through the window he was shaking his head approvingly and said; “This is it. Please don’t make it any darker. ” It was not easy to re-enter the bank and to get rid of the ammonia gas. Our noses and eyes were running, but my tears were tears of joy. We touched up the small areas that were unaffected by the gas, and the bank opened up as scheduled.

But I was not there to see it. Fernan said, “You, fellow, I don’t want to see you for a week. Go and have a good time at DeauviIle ,” and stuck about a month’s pay into my hand. On July the 15th I lost my last franc at the roulette table. Luckily I had my return ticket, and on the 16th I was back and happy at my workbench.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Bahco 6-Inch Card Scraper

Diablo ‘SandNet’ Sanding Discs

Comments

Great read. I have his book (adventures in wood finishing?) and read it years ago. If you can find a copy get it as it an enjoyable read.

This is one of my favorite stories from the early days of Fine Woodworking and I'm glad to see it called up again for a new crop of readers to enjoy.

One thing I've missed in the way Fine Woodworking has evolved through the years and as it's become such a polished thing is this kind of tale.

Woodworking to me, is an adventure. Things go wrong and we adapt, and grow and learn when someone (usually ourselves) has screwed up. There's value in the human interest tale. It reminds us of our own humanity. It directs us toward humility, and connects us with each other at a deeper level.

Well said DougStowe. As much as I hate it when it's my screw up I always learn from it and other people's mistakes.

I've arrived at the conclusion that woodworking is partly about skill and creativity, but also about forgiveness. The faster we forgive ourselves for our own mistakes, the faster we get back to work. And mistakes are always an opportunity to learn. Viewed from the perspective of the iPhone 11, the Newton was not a mistake, but a step in the right direction.

Yara, one of the world’s largest producers of nitrogen fertilizers, is banking on ammonia becoming a preferred zero-carbon shipping fuel along with opportunities in existing fertilizers and industrial applications.

Ammonia is the most promising hydrogen carrier and zero-carbon shipping fuel, and Yara is the global ammonia champion,” Chief Executive Svein Tore Holsether said in a statement. For more best information click here Farmers & Merchants Bank (Missouri) login

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in