Fair enough

For Nancy Hiller, there is a lot more to coming up with a fair price than calculating time and materials.

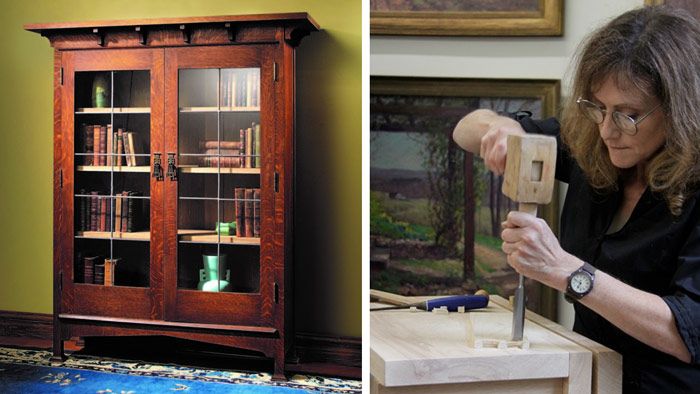

Last summer I published a post at the Lost Art Press blog about one of those experiences familiar to many who build furniture for a living. A reader of my Popular Woodworking article about an English Arts and Crafts bookcase, who mentioned that he was retired, had written to say he’d built a bookcase inspired by mine. “I’ve recently been asked to put a price tag on it for a possible commission,” he wrote. “But I’m not sure what to say. Can you help?”

I had sent back a concise and respectful note, replying that it was not for me to tell him what to charge for his work, because (in a nutshell) every maker’s circumstances are different. What I charge, as someone whose livelihood depends on the furniture and cabinetry I build, has nothing to do with what he may be in a position to charge, as someone who’s retired.

I published the post about the above exchange because it was one of those questions with which many of us find ourselves faced – questions based on assumptions (often unconscious, and almost always innocent in their intention) that deserve to be brought to the fore. I don’t know whether the writer was asking me to share the specific figure I would charge for the bookcase, or requesting instructions on how to go about calculating what he should charge. The former is irrelevant in this case, and a full answer to the latter would have required a lot more time than I could give.

Google “how should I price my art?” and you’ll find 4,660,000,000 results. Woodworkers are some of the loudest in lamenting the challenge of putting a price on their work. Some of us have written elsewhere about how we come up with our pricing; this stuff is out there online, free to anyone who bothers to seek it out and read. Deciding how to price your work takes some thinking, some effort.

A reader of my post commented that he was disappointed by my response. He said it was “unfair, arrogant, and selfish” of me not to have suggested “a fair price” and expressed his belief that I “could [not] care less.” Ever since, I’ve had in mind to write about what might constitute a fair price, because the matter is far more nuanced than this righteous commenter seemed to appreciate. Let me underscore that this post is not about pricing your work. It’s about the concept of a fair price this reader invoked.

The first step in addressing this matter is to think about what we mean by the word “fair.” Woodworkers of a certain age will be familiar with the definition of fair as lovely. A weather report may call for fair skies; a woman may be described as fair of face. The woodworking term “to fair a curve” goes further, referring not just to making a curve pretty, but in many cases also to shaping one curved part to fit another.

Each of these meanings implies a detail that’s easy to overlook: Fairness isn’t just one-sided. It always involves a perceiver and something perceived. As a consequence, any serious determination of fairness will depend on variables pertaining to each of these in a given situation. Taking this particularity into account is all the more important in cases where we’re using the word “fair” in its most widespread contemporary use: to mean “just” or “equitable.”

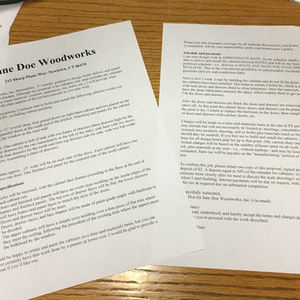

By way of illustration, let’s return to the reader whose request for help with pricing prompted my original post. Here are some of the considerations that typically factor into pricing. Beyond the cost of materials, my charges need to cover my living expenses, shop overheads, and a variety of costs (among them several types of insurance, permits, and taxes) associated with running a business as a business, i.e. in accordance with legal and municipal requirements. On the other hand, because I depend on this work for my livelihood, I have to keep jobs coming in; paradoxically, this sometimes translates to doing what I can to charge less than I might otherwise, in an effort to keep my work affordable. When it comes to pricing, the minimal definition of fairness (in the sense of justness) to a maker is that her charges should cover her cost of living and doing business. For the customer, fairness in this same sense has more to do with the maker being honest and transparent about what she is going to charge, and the basis on which she will do so (i.e., will she work for a fixed price, on a time-and-materials basis, or according to some other plan?).

If I quote a prospective customer a price of $10,000 for a set of built-in bookcases based on the labor, material expenses, and related costs of doing business that my records show it cost me to build a similar set in the recent past, the customer may consider the price unfair in the sense of unattractive, i.e. more than she is willing to pay. No one can argue with that, though in such a case I would do my best to explain why the work would cost what I quoted. Even so, a quote based on what I know the job would cost me to build is fair to me, and I am one of the essential parties in the relationship. On the other hand, if the price I quote is affordable to her and within the range of what she imagined she would pay for the work, it’s likely to strike her as fair in the sense of attractive.

What someone else, amateur or professional, might charge to build a similar piece is irrelevant to the fairness of the price I quote, and vice-versa. Again, every maker’s circumstances are different. Furthermore, there is no law or ethical obligation that requires me to charge only what my work costs me to make, or to keep my charges below some imaginary maximum price; I can in principle charge whatever price I want, as long as my customer is willing to pay it. If we are both happy with the arrangement, it is by definition fair.

A maker who does not depend on building furniture for his livelihood and is free from the kinds of operating expenses that go with running a business can charge as little as he sees fit. Is there any professional who has not heard a prospective customer say she’s going to see if her friend Bob, the retired shop teacher, can build the kitchen island you just quoted for less? Fairness, in the sense of justness, is really not an issue here (unless you want to talk about the arguable unfairness of those who don’t need the work for their livelihood competing against those who do, but that’s a different discussion). If the bookcase commission is for a friend, the retired maker doesn’t necessarily even have to charge for labor; he may decide to charge for the materials alone. Alternatively, because he doesn’t strictly speaking need the job, he is free to quote as high a price as he may wish. Nothing makes it easier to quote art-world prices than the security of not actually needing to make a sale.

Equally important in considering the meaning of “a fair price” is what we mean by the word “price.” At this point in American economic history most of us are so accustomed to thinking as consumers, trained to equate optimal value with the lowest price, that we’ve forgotten the more nuanced meaning of “price” – i.e., value, or worth. Most of the things we buy on a regular basis are so far removed from any sign of their makers and from any record of their making that we see them less as artifacts (literally, things made by means of skills) than commodities (stuff to be bought). Price has been reduced to a number. But as with the concept of fairness, worth (or value) is relative. A diamond ring may be worth $10,000 to someone very wealthy, but if you’re starving, it’s of less value than a potato.

Bottom line: A fair price is one that compensates the maker adequately, and one that the buyer understands reflects the care, skill, and materials invested in the object’s making. It is not an abstract number, but a measure of a relationship. This is why I cannot simply suggest “a fair price” for someone who builds a piece based on my design to charge a prospective customer.

*Thanks to John Cashman for reading a draft of this post, providing constructive comments, and suggesting the title.

|

|

|

|

|

Comments

As a hobby woodworker I've made dozens and dozens of items that I've given to people without any price attached. The nature of a hobby activity is essentially that you do it for enjoyment, not for money. Would I charge a fellow new member of the bike club for advice about cycle racing? Or the friend recently widowed for teaching him how to boil an egg and many other cooking procedures?

No.

It's regrettable, as you mention, that people these days often seem to know the price of everything but the value of nothing. Many values have nothing to do with cash value. Every transaction and relationship does not have to be a business or commercial one.

Personally I enjoy the notion that there is indeed something that's a free lunch, especially if I'm the supplier. :-)

Lataxe

Kudos for a well written and well thought out response to a too often asked question. When asked, I have developed the habit of responding with "You need to decide what amount is enough for you to build something like that; there's your price."

When I'm talking to someone I more regularly discuss these facets of the craft with I will always add that their market has to be assessed to see if it will support the amount they need to make. Bel Air, CA is more comfortable with some pricing than Bakersfield, CA (no offense intended to the residents of Bel Air or Bakersfield).

Fortunately for both myself and professionals like Nancy, I, like most amateur retirees, am slow enough at this stuff that I can't afford to sell my pieces or compete with the professional shops for commissions. While I consider myself an intermediate level woodworker, and I'm sure I could tackle the Arts and Crafts bookcase she was discussing, it would take me so long to do a job that resembled her quality and attention to detail, that any price I put on it would mean that I was working for pennies an hour.

I do this stuff because I enjoy the projects themselves. I do projects as gifts for friends, pieces for our own home, and to appease my spouse. But if I wanted to start selling them and make a profit, I might as well have stayed at my day job, something I was very good at and very well paid for my time.

I guess I also have to point out how disingenuous it is to not only take someone else's design, granted it was published, but then to ask them how to price it, so as to steal the business. He is either taking Nancy for a liar or a fool. My response would have been much less kind than hers was.

Well said Nancy Hiller, and I am saddened that the comment on your original blog post was so negative. As you stated so eloquently, it is a far more complex subject than this gentleman's innocent question captured. There are renowned woodworkers whose names alone command a higher price simply because they are recognized, and those who might have equivalent skills but less demand and therefore charge less for their work. Hopefully this article can inspire thoughtful conversation both about pricing, and about how we might discuss various topics without assuming ill intent.

Hi Nancy,

I've been a professional woodwork estimator for most of my career beginning with my own shop in Spain and ending with a job as the Vice President in charge of estimating for a large architectural woodwork company in Minnesota.

First, understand the science of estimating, figuring the cost based on labor and materials. The material cost is a replacement cost including all waste and overhead. The labor cost per hour includes direct and indirect costs. This is important because you gain confidence knowing the bottom line cost.

Second, understand the art of selling. The best scenario is no competition whatsoever. This happens when your work has no equal (to one customer at least). If your work has competition, find success because your work is admired and provides great value.

Above all, understand your market and believe in your work.

Warm regards,

Paul Nielsen

As always an excellent article Nancy and as are the previous comments.

I've been a consulting engineer for over 30 years and a engineering firm founder and owner for 19 years. During that time my regular duties involve estimating and negotiating pricing for occasional small projects priced at a few thousand dollars, but mostly for projects priced from tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars having total construction pricing in the tens of millions of dollars.

Although, as a service provider we use the term "total fee" instead of price, the principals outlined in your article and by the previous commenters hold true in the engineering industry as well. One difference is competitors in the engineering industry have legal access to one another's detailed scope of work, estimated and actual costs, and total price once a public project is contracted and again when is completed. Obtaining and knowing a competitor's specific pricing for a specific project is only used for spot checking specific costs such as the price per board foot for a specific material or the number of hours needed for a specific task. Although the total price is known, as you mentioned that price is generally irrelevant when providing a total price for our future work. I learned from old grey haired master estimators who built the Hoover Dam and San Francisco's Bay Bridge that the total price is the resultant of the "detailed costs and our ability to mitigate risk involved in doing the work."

Risks involved and mitigating risk can be a whole topic for a future article.

The timing of your blog post literally could not be better. I had just sent a question to the Shop Talk Live email, touching on this issue.

Although being a hobbyist woodworker myself, I'm now hoping to commission a few pieces I would like built. I'm blessed to be in the position to do that. They were largely projects I imagined I'd build someday (but not the projects I want to build for their own sake) - but seeing the economy pro woodworkers are going to have to navigate, I would now much prefer these become projects I hire out.

So even though I appreciate what materials cost and how much labor different projects take, I appreciated that there's more to the arrangement to that.

I'm hoping to find a win-win, and avoid being either a difficult client or patronizing. Until perhaps a few years ago, I never imagined I'd be in such a position - I have no idea how any of this works.

Great article Nancy. It's a topic that comes up often, for both professionals and amateurs. It's probably tied with "How long did tgat take to build?" as the most common queries.

I love your line that a fair price is "not an abstract number, but a measure of a relationship." Thats it in a nutshell.

The best answer to pricing woodwork I have heard came from chairmaker/instructor Drew Langsner. He said his reply was "Well, it took me a week to build it... How much do you make in a week?" This covers both the question of fairness (or at least equity) and allows the buyer to see the real world comparison of labor.

Nancy, I could read your comments all day long. Eloquent, intelligent, diplomatic and "bang-on" (as we say this side of the pond).

Thank you.

The picture of book case looks awesome. I am a hobbyist/ making some extra money in retirement. When I build something special I set a price and if some one wants to buy it good, otherwise I keep it. There is no rime or reason for the price. If I get tired of it I will reduce the price to get rid of it.

The quality needs to be communicated to the client. My solid wood item is not what you would fine in a discount store that is mas producing a similar item, with very poor quality. Some items that I make in bulk, I will negotiate the price, some what. So now I have money to take the grand kids out and have fun.

I asked a professional woodworker to tell me what I should have charged for one of first pieces of furniture I sold. After telling me I should have charged $1,700.00 I told him I had charged $1,100.00. He gave me a bit of a lecture, one that I appreciated. He said, "Your client will be very happy, and will tell her friends. Her friends will come to you for your work, and will expect a similarly low price for it. This is natural, but these people are showing a lack of respect for you and your work, and eventually you will lose respect for yourself." The lesson I took away from this was: either give it away as a gift to someone you like or sell it for what it is worth.

Hi Nancy... i enjoy your writing very much and certainly appreciate your work. i do not do woodworking full time, but have strongly considered trying to sell works to supplement my income and to prevent me from filling up my house with items i have made (i do period reproductions mostly with hand tools). i have wrestled with this very issue and i think your answer(s), while indirect, are spot on. i have spent 35 years in new business development and have had to place value on all sorts of new products. every time the issue goes well beyond time and material. Obviously one has to cover ones costs and turn a profit or you will not be at it for very long. one has to set aside some of those profits to replace tools as they wear out, expand ones capabilities, etc. and then there is the value of something increasinly rare these days, a hand made or bench made custom crafted item. in a time where commercial items slap a label in big bold letters stating "real wood!" shows how far we have moved from pieces of furniture that are unique, kept in the family for years (and last for many years) and where the owner has some say in how they appear, what they look like. it is a balancing act between what someone is willing to pay and what the maker needs the price to be in order to proceed with the work. there are no clear cut formulas. what would the maker have to receive in order to be willing to do it again for another customer? if you put in an extraordinary amount of work, create a beautiful piece, the customer is really happy, but you would never ever do it again for what you made from the first one, you did not charge enough. it comes down to the value of the intangibles... just like real estate, the value is what someone is willing to pay. that influences what one charges, what one makes. if you are doing it simply for the love of the craft rather than to put food on the table, you can afford to make a piece that appeals to only a narrow segment of the market and can afford to sell it for what someone is willing to pay. if you need to support yourself, your family, etc. then those circumstances dictate something in the pricing. Sadly the market for fine woodworking is perhaps narrower than it used to be. having said all that, woodworkers need to have respect for their craft and themselves, and remember it is always easier to come down than to go up. As one responder put it, it is a matter of respect.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in