Learning a craft

Vic Tesolin believes that a good teacher inspires you and makes you want to learn, but beginners should be careful who they learn from.

When I started woodworking, the internet was supposed to be a fad that was destined to fizzle out in a couple years. This means that before I attended Rosewood Studio for formal education, anything I had learned about woodworking I learned from the printed word. Books and magazines were the only options available to me…that and actually getting into the shop and working wood. Reading about and studying the theory of woodworking will get you about 20% there. The real learning comes from doing. Long before me, in different parts of the world, there were apprentices—people indentured to a master who would learn from them, then take their tools on the road to work for other shops where the learning would continue.

None of these budding woodworkers spent time on the internet in chat rooms or on forums reading about woodworking. They simply learned from someone who knew what they were doing and who was willing to pass on their knowledge and craft. They didn’t have in-depth discussions about wear-bevels or which sharpening method yields a sharper edge, and there were no grainy Japanese videos to draw myriad conclusions from. Nope, these folks just toiled for hours at a stone or a workbench and gradually got better at it. The results (or lack of) were quite apparent on the pieces they were working on. If they got tearout on a board, they would just go back to the sharpening stone to refresh the edge. Hard work and perseverance (and often a grumpy master) spurred them on to better results.

We are lucky nowadays. There are experts on woodworking, metallurgy, design, and technique on any number of forums, ready to give you the advice (or berating) that you are looking for. No proof of their abilities is required, no portfolios or experience. Just a bold voice in a small corner of the internet where they are lurking, waiting for someone to ask what they would consider a “stupid” question. Pages and pages of keystrokes, all to debate what a talented woodworker friend of mine would define as “how many angels can dance on the head of pin.” I’m not sure why forums are so adversarial. Perhaps it’s the relative anonymity they provide. In my experience, woodworkers are great, friendly people who are more than willing to spend time talking about their craft. Having open-minded conversations about woodworking is how new skills get learned and new ideas discovered. Nobody ever learned anything from dogmatic, single-minded vaporing that leaves no room for discussion. Let’s be real here: There are many ways to cut dovetails and if a technique yields good results, what’s the problem?

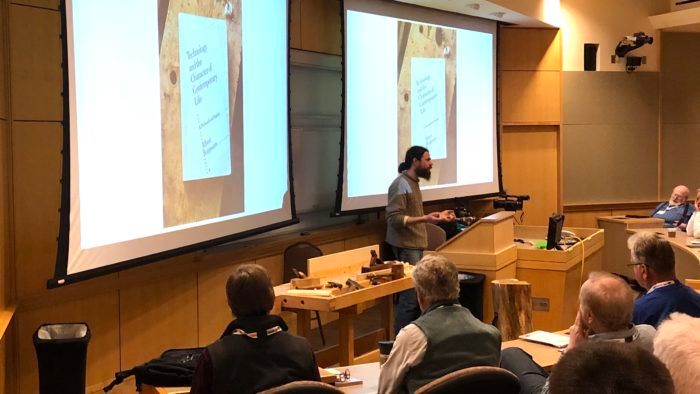

Teaching anything is not easy. A good teacher inspires and makes you want to learn. A good teacher can draw on years of experience to help a student understand the fundamentals of any skill or craft. A good teacher can see the look in a student’s eyes and know when they aren’t getting it and can instantly change tack and re-explain things to clarify the point. I was fortunate to have studied with some of these teachers, and they taught me more than woodworking. Some of the best woodworking teachers in North America have taught me about business, humility, patience, and marketing, on top of how to properly cut joinery or lay down a finish.

My advice to any beginner woodworker? Be careful who you learn from. Read books and articles from authors who have been published; this ensures that they have been vetted and edited by other professionals or their peers. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Keep an open mind and never stop learning. Most importantly, get into your shop and work wood.

In order to understand, you must do. – V

Comments

Good advice, as always. Thanks.

Wise words. My first woodworking course (taken in the Pac NW) was from a frequent contributor to this magazine. During the 2 week, very expensive course of the 8 who started, 2 dropped out a few days before the course ended no longer able to take the abuse that this so-called teacher doled out. He was unprofessional to the extreme, and we only learned anything those 2 weeks in spite of him. Luckily I've had some wonderful instructors since that time, but it definitely pays to do some research as there are some very bad teachers out there, some of whom actually own and run woodworking schools.

For those who have gotten past the "quick and easy - with amazing results!" dragon chase, you could do worse than to check out Rob Cosman's recent 35-part series on making a drawer.

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLTS2AB76bnu0sjF-3kEeBzDEBUcYnHVpL

We live in a great time for woodworking. We have a better range of outstanding tools, books, and videos than ever. And we can take classes from outstanding masters of the craft. It's like being able to learn how to paint from Picasso or Monet.

I've taken classes from some of the very best, and I'm thankful for the opportunity. They have taught me more in a short time than I could have on my own.

"Sitting with Nellie" to learn a procedure of work was often used, not just in woodworking apprenticeships. As the article intimates, Nellie could often be a poor example, not good at the work or explaining it. In my experience, for every good Nellie there were nine poor ones.

In learning woodwork I relied heavily on books and magazines as the guide to making all my mistakes that I learnt from in the shed. They were made on more ambitious projects as a result; and more quickly corrected via facilities such as the old-time Knots forum of FWW. (I regret greatly it's demise and reduction to the current rather lacklustre place).

Lately I've been viewing the FWW videos. Many are now excellent, with good production values but also excellent presentation and explanation by fine teachers. I'll mention Chris Gochnour's Enfield cabinet and Mike Pekovitch's small cabinet videos; but there are many more.

Perhaps one day FWW will have a live-class via video conferencing facility too? That would have the potential to speed up the rather slower forum-posting interchanges that I learnt so much from in Knots. I suppose those "woodworkers sitting 'round a table gassin'-on" items are a beginning but they would be better focussed on actually making something in a shed (shop) with questions and answers arising from the doings.

Lataxe

I build furniture (the picture I tagged to this post is one taken from a reproduction I made following Norm Vandal's book on Queen Anne furniture)-- I also pioneer group pedagogy for engineering students. There is a balance between what I call "scaffolding" and experience. No scaffolding, you may get it right the first time. But with proper scaffolding, generalizing from your experience gets far easier.

So read those woodworking magazines, study the photos for maximum effect, and by all means, learn the vocabulary of the craft. Words open up avenues through increasing awareness. That's the scaffolding. But then get down and build something. Because we only develop the ability to use knowledge when we form our own autobiographical narratives. For those interested in how this works in your brain, well, here you go! https://empathy.guru/2016/07/03/the-neurobiology-of-education-and-critical-thinking-how-do-we-get-there/

I read that paper on the guru-empathy stuff. Hee hee - only a Yank academic could dress up a quite simple and effective notion in such a splurge of arcane and esoteric language borrowed from here there and everywhere, with a dollop of religion tossed in. Hot & warm gods! Hee hee hee.

Still the proof's in the pudding, I suppose - which is students emerging with an ability to do critical thinking across different domains of practice, as well as the various practices, in an effective fashion.

Lataxe. a foreigner separated by a common language.

Might be obvious to you -- but you'd be amazed at how many people fight the notion. Otherwise we'd all be better off!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in