Back to work

Colonial Williamsburg's 2021 conference aims to look at period furniture making from a new perspective.

An active workshop is a terrible place for a finished – or nearly finished – piece of fine furniture. Surely I’m not the only one who reaches this conclusion as a project nears completion. It is a stark contrast: intricate ornament and polished wood amid the dusty, roughsawn realities of a space filled with tools designed to chew up that same wood and spit it out. This not only makes me nervous (and careful), but it also awakens the historian in me. Most of the people working in high-end 18th-century cabinet shops could not afford their own work. The contrast between places bites a little harder when we expand it out to include the people who inhabited those spaces. We’ve designed this year’s Working Wood in the 18th Century conference, held virtually from Colonial Williamsburg, to frame our many woodworking demonstrations within these contrasting and/or overlapping contexts of home and shop.

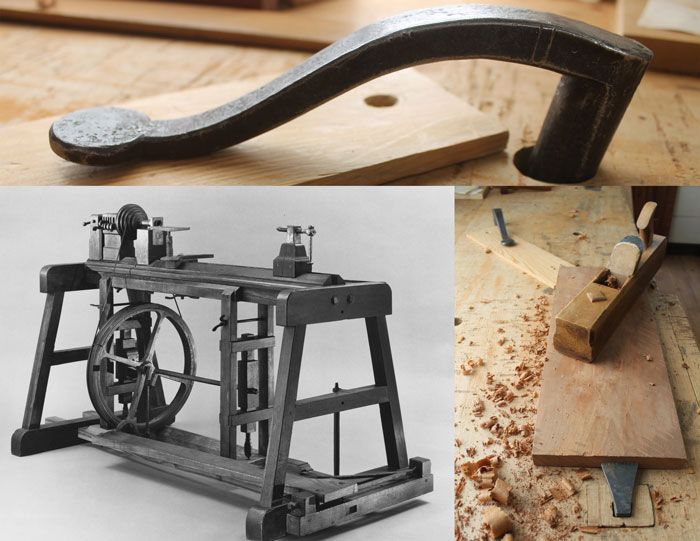

On its surface, our theme, “Back to Work: Functional Furniture for Home and Shop,” may seem like a tie that loosely binds a series of interesting pieces and topics together. There are, after all, many interesting pieces to consider during three and a half days of period-appropriate how-to demonstrations. Among the highlights from the workshop side of things are workholding techniques and staked stool construction with guest presenter Chris Schwarz and the construction of a treadle lathe with Colonial Williamsburg’s lead joiner Brian Weldy. Of the fine furniture associated with the kinds of work performed by the gentry in their homes, we will feature guest presenters Bob Van Dyke and Mike Mascelli demonstrating a neo-classical work table (a popular form designed for storage of needlecraft supplies), Hay Shop apprentices John Peeler and Jeremy Tritchler making an intricate apothecary chest, and me demonstrating a writing table that can adjust in height and angle. In other words, all the stuff that you’d want in a typical hand-tool-centered conference: turning, tool making, holdfasts, veneer, tiny dovetails, upholstery, round mortises, square mortises, and on and on, BUT…

…we don’t want a typical conference. For the many decades that period furniture making has been a thing among modern woodworkers, the normal approach has been to rip furniture out of its original context and park it in our modern homes and lives. There’s nothing wrong with that, like there is nothing wrong with cutting a cabriole leg on a bandsaw. The past is an inheritance that we may spend as we desire. It is also a lot more than that. The lessons and stories we tease out of it may often be contradictory or inscrutable, but they are also a vital force in our lives. One of this conference’s chief goals aligns nicely with the aims of many current period furniture makers and historians: to restore context to the how-to lessons we glean from the past. It’s easy to treat these procedural lessons as detachable from their historical contexts. By practicing traditional techniques today, we do our part to ensure their timelessness. We do ourselves a favor when we also consider that these ways are of particular times and particular places. The mix of topics we’ve chosen for January’s conference highlights stark contrasts and surprising similarities among diverse forms, places, and people within the nebulous time frame when what we call period furniture was first created.

Mixed in with the many presentations on individual pieces and techniques are several that focus on the people and places associated with them. The apothecary chest featured in the conference came from the well-known London shop of cabinetmaker Philip Bell. How many period makers know about his wife Elizabeth, who was an important figure on the London cabinetmaking scene for many years? Amanda Doggett, joiner, and Melanie Belongia, harpsichord maker, will host a panel discussion/Q&A on women in the woodworking trades (there were more than you think). We’ll also hold a panel discussion on black tradespeople, enslaved and free, then and now. All early American woodworking trades were entangled with slavery, be it in the skilled trade work itself, the procurement and transport of materials, the use of the finished good, or in the wealth behind the purchasing power that drove the work in the first place. Carpenters Ayinde Martin and Harold Caldwell along with coachman Adam Canaday will share their thoughts on the complex combination of tragedy, perseverance, and skill that surrounded the black tradespeople who helped build some of early America’s most iconic structures and furnishings. They, as African Americans, will also reflect on their own experiences interpreting this history to the public every day.

The power of contexts and contrasts struck me with particular force on a recent morning as we were filming a program at Williamsburg’s Peyton Randolph House. Randolph, one Virginia’s most powerful men, lived with his family in a house that suited his stature. The house is an original building, but its massive complex of kitchens, workrooms, and outbuildings were reconstructed 20 years ago by Colonial Williamsburg’s carpenters based on archaeological, architectural, and documentary research. In the past our conference has tended to emphasize the interiors and furniture found in places like the Randolph House, but this year we will turn our attention to the two-story kitchen, the enslaved families and individuals who lived and worked there, and the many enslaved craftspeople who would have built the original structure. Supervising interpreter Janice Canaday and master carpenter Garland Wood began their tour seated in the Randolph’s well-appointed parlor and ended in the unfinished, uninsulated attic rooms above the kitchen that would have been the sleeping quarters for Randolph’s many enslaved workers.

Garland’s story of construction techniques intertwines with Janice’s story of the lives lived in those kitchen spaces to present a fuller and more nuanced picture of colonial life than either of those subjects could by itself. Building techniques arose from their historical contexts and can best be understood alongside them. The writing table that I’m building is normally surrounded by valuable books and furniture in Mr. Randolph’s office (the table is appropriate for the room, though not original to it) (photo below, left). Not only is this likely a very different kind of room than the shop in which it was made, its more immediate surroundings put forth a far more powerful contrast: See, for example, the pallet beds laid out on the hard floor of the kitchen attic (photo below, right).

It is in this spirit, putting things in context before we bring them forward to use in our homes and shops, that our conference will unfold. When Chris Schwarz studies paintings for clues to period work holding, he also engages with their context, whether it’s 17th-century Peruvian Christianity or 1st-century Roman mythology. When Bob Van Dyke started thinking through the work table he’s making, he decided not to gloss over the upholstered bag as many would – it is the heart of the table’s purpose after all. Instead, he invited along master upholster Michael Mascelli to dive deeply into its construction and use. This kind of thinking is why we’ve invited these presenters to join us. We hope you’ll join us virtually this January 14th-17th as well. For many of us, 2020 blurred the lines between work and home, so early 2021 seems like a good time to grapple with how working and living were woven together for better and worse in early America.

|

|

|

|

|

A very good cabinetmakerWiltshire worked in the cabinet shop owned by Anthony Hay, and like the building he worked in, the “very good cabinetmaker” was Hay’s property. |

Comments

This is a time in history when it feels like society is split between moving forward in the light of historical truth or backward, sheltering under old, toxic myths. I thanks and congratulate Mr. Pavlak and the editors of Fine Woodworking for choosing the side of light.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in