Make a wooden pull plane

Vic Tesolin's wooden pull plane is not a Japanese plane, but his own version that cuts on the pull stroke instead of pushing like a standard western plane.

Synopsis: Vic Tesolin’s wooden pull plane is not a Japanese plane, but his own version that cuts on the pull stroke instead of pushing like a standard western plane. Constructed of two core pieces and two cheeks, with a wedge that holds the blade secure, it takes about a day to make.

A couple of years ago, I was exposed to Japanese plane making. A friend let me try some of his planes and I fell in love with them. They feel nimbler in my hands, and I feel like I have more control over what I’m doing on the pull stroke. But after a few failed attempts at trying to make a Japanese plane, I realized it was not an easy task. They don’t have any flat surfaces and the blades are tapered in two directions.

I truly enjoy pulling planes, so I set out to simplify the construction for a pull-style plane. I’m not making a Japanese plane. I’m simply making a plane that you pull instead of push.

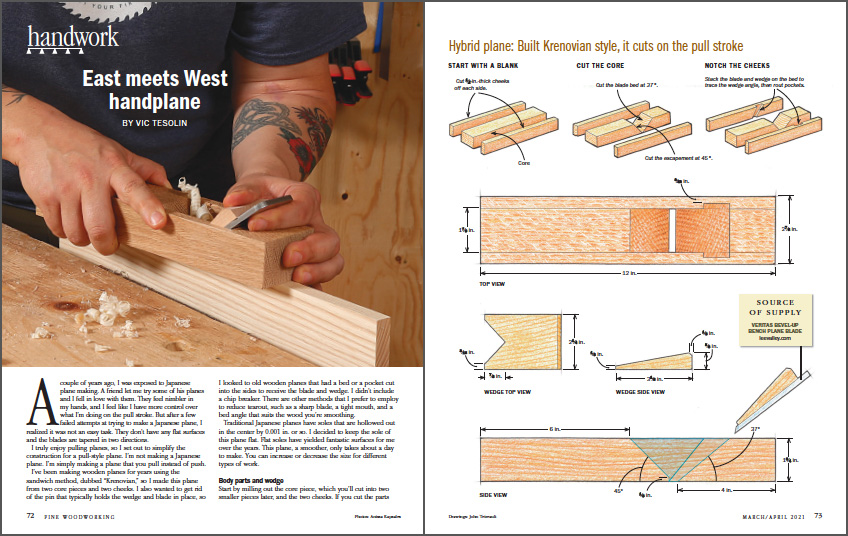

I’ve been making wooden planes for years using the sandwich method, dubbed “Krenovian,” so I made this plane from two core pieces and two cheeks. I also wanted to get rid of the pin that typically holds the wedge and blade in place, so I looked to old wooden planes that had a bed or a pocket cut into the sides to receive the blade and wedge. I didn’t include a chip breaker. There are other methods that I prefer to employ to reduce tearout, such as a sharp blade, a tight mouth, and a bed angle that suits the wood you’re smoothing.

Traditional Japanese planes have soles that are hollowed out in the center by 0.001 in. or so. I decided to keep the sole of this plane flat. Flat soles have yielded fantastic surfaces for me over the years. This plane, a smoother, only takes about a day to make. You can increase or decrease the size for different types of work.

Body parts and wedge

Start by milling out the core piece, which you’ll cut into two smaller pieces later, and the two cheeks. If you cut the parts from the same blank, you can maintain the grain picture, but it is not necessary. Crosscut the bed at 37° and the escapement at 45°. Lay out the wedge, cutting the slope on the bandsaw, and clean up the milling marks.

I make pockets in each cheek for the blade and wedge to slide into. To lay out these pockets, clamp the bed part of the core to one of the cheeks and transfer the bed location to the cheek.

From Fine Woodworking #288

From Fine Woodworking #288

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

Japanese Planes Overview with Andrew Hunter

We’ve got a plane down!

Wood Planes Made Easy

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Lie-Nielsen No. 102 Low Angle Block Plane

Bahco 6-Inch Card Scraper

Veritas Micro-Adjust Wheel Marking Gauge

Comments

The Krenov method of wooden plane-making was invented partly to avoid the necessity to make "pockets" on the inside of the mouth to hold and guide the blade-retaining wedge. A crossbar is used instead.

The crossbar is easier to make and install correctly, especially for a first-time maker. Wear, compression and distortion in the wooden wedge are far less likely to become a problem with a crossbar than they are with pockets inside the cheeks, which have to fit the wedge exactly. Wear of the crossbar is also a non-issue whereas wear to the pockets in the cheeks will soon adversely affect the ability to place and retain the blade.

Why has ole Vic done the pocket thing then? Because he could, perhaps. :-)

Lataxe

I like wooden planes and think this one should be relatively straightforward to build -- but I have not built a copy, yet.

I am concerned about the bedding angle of 37 degrees. Combined with a standard bevel angle of 30 degrees on the bevel-up blade, this implies a high cutting angle of 67 degrees. If we flip the blade bevel down, there is only 7 degrees clearance under the bevel. Neither seems ideal.

At bedding angles below 45 degrees, the majority of the force on the blade pushes the blade back, out of of the plane body. Without an adjuster backstopping the blade, those forces may make it harder to maintain the blade setting. One solution to this is to use a tapered blade, which wedges itself in place harder as the blade gets pushed back by the cutting forces:

https://www.leevalley.com/en-us/shop/tools/hand-tools/planes/blades/71259-veritas-tapered-plane-blades

Alternatively, a relatively easy modification would be to raise the bedding angle to 45 degrees or more. At those angles, you can use the blade bevel down. At bedding angles of 55 degrees or more, you can also reverse the blade to the bevel up position for a scraping cut.

If I had built or described this plane, I might have easily confused some angles. Setting a 37 degree angle on a bevel gauge and then measuring "naturally" from the vertical implies a bedding angle measured from the horizontal of 90 - 37 = 53 degrees. That would seem well within the standard range of bedding angles for bevel-down blades.

Thank you,

Ludger

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in