Frank Wiesner, living treasure

There are many excellent designers and craftsmen of both yesterday and today, but Frank is different.

Altgeselle is the traditional German term used to distinguish the most esteemed and skilled senior cabinetmakers. Such tradesmen are mentors for the young and are best equipped to impart knowledge on those willing to listen.

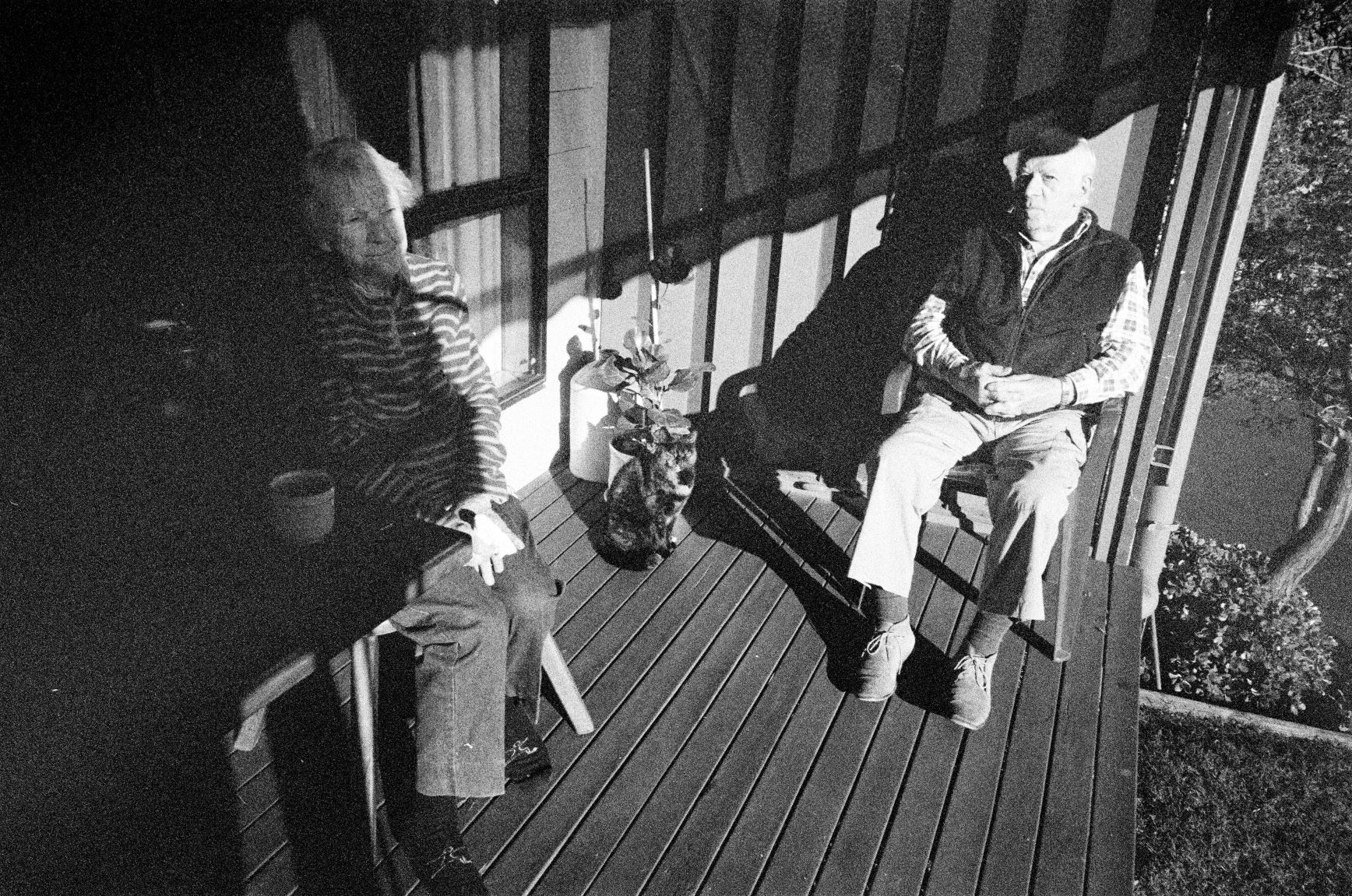

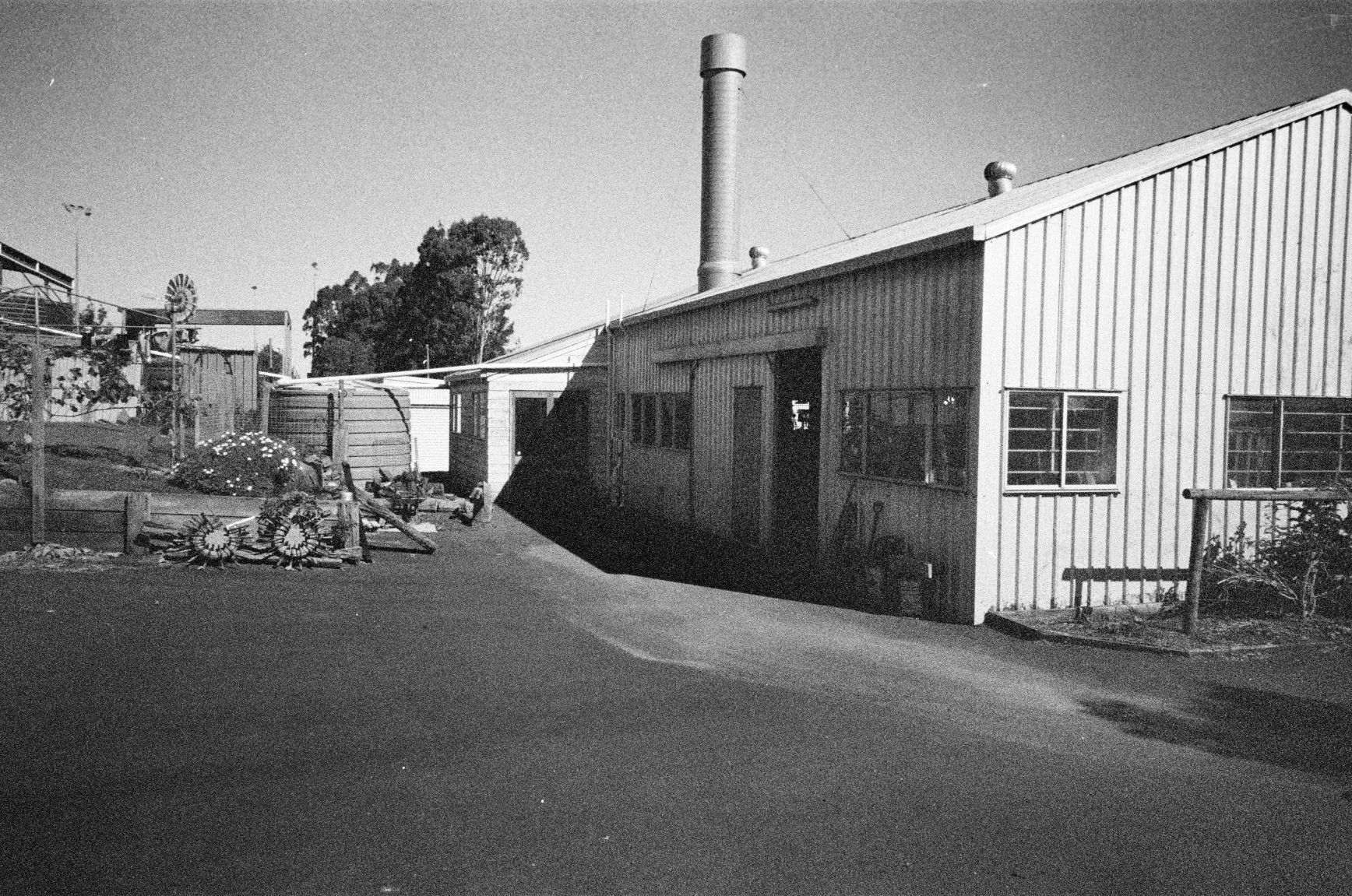

There is a small street in Northern Toowoomba, Australia, where a hidden gem may be found, a nondescript property that is easily passed by. Stroll through the wire front gate and down the driveway and two kind-hearted folk will shout a hearty greeting at you from the porch where they sit after breakfast, facing north, soaking up the warm morning rays of sunshine.

Meet Frank and Joan Wiesner, married for over 65 years and with such welcoming hearts that they make you feel right at home. For those who have been involved with woodworking for more than 20 years, the Wiesner name is synonymous with woodworking of the highest caliber. For those new to woodwork, it is a name worth investigating.

Meet Frank and Joan Wiesner, married for over 65 years and with such welcoming hearts that they make you feel right at home. For those who have been involved with woodworking for more than 20 years, the Wiesner name is synonymous with woodworking of the highest caliber. For those new to woodwork, it is a name worth investigating.

Frank Wiesner is a cabinetmaker by trade. Trained in the notoriously strict and stringent guild system of Germany, Frank started his apprenticeship in occupied Berlin in 1948. His master, Joseph Schirrmacher, was a strict and traditionalist man whose workshop utilized manual labor, not because it was trendy, but simply because this was the way it was done.

At the completion of his formal training, Frank departed for Australia with a group of skilled German tradesmen in search of excitement and a new world. His travels led him first to Melbourne and then to Queensland where Frank worked on remote dairy farms, building furniture on the side. It was here that he met Joan, the love of his life.

Those early days of freedom, limited only by the range of his Enfield single-cylinder motorcycle, had a profound effect on the couple. Under Joan’s encouragement, Frank re-entered the trade of cabinetmaking and shopfitting, working for well-known joiners such as City Joiners in Toowoomba, producing work that was showcased in many bars, restaurants, and heritage-listed buildings in the remote Queensland outback.

A short time later Frank met the highly influential Robert Dunlop, himself trained by the Swiss master cabinetmaker Charles Kuffer in the 1930s. The two became very warm friends; their personalities and training yielded a connection, understanding, and deep mutual respect rarely found today.

Robert challenged convention and encouraged out-of-the-box creativity, thus providing the catalyst for Frank to realize and express his own creativity in furniture design. Frank’s furniture soon found its way into the houses of both the wealthy and the needy, as Frank does not discriminate. It is his firm belief that a craftsman should not turn up his nose but rather welcome any query without prejudice.

There are many excellent designers and craftsmen of both yesterday and today, but Frank is different.

Frank has the ability to observe, analyze, and understand timber not just aesthetically, but also with the mind of an engineer – understanding how to manipulate timbers to exploit their inherent mechanical, chemical, and aesthetic properties to the fullest. Frank lives his professional life by what he calls his “bible” – a 1928 copy of The Timbers and Forest Products of Queensland by EHF Swain. Years of studying the unique timbers contained within these pages in theory and practice, by means of his own detailed testing methods, have rewarded Frank with an incomparable depth of knowledge on the topic.

Toby’s Estate: The Craftsman series – Frank Weisner from miklos janek on Vimeo.

The phrase “farm to table” is commonly used today to describe how the most dedicated and decorated chefs grow and harvest their own produce to create spectacular award-winning dishes. Frank is perhaps one of a very few who have applied this exact ethos to furniture making. He started doing so decades before this fashionable term was coined.

Frank’s approach tackles the full timber life cycle, from the growth of the tree to the finished product and through its serviceable life, concluding with inevitable disposal.

From the early 1970s Frank was a familiar sight, with his Homelite Alaskan chainsaw mill slabbing fallen trees not only in residential areas, but also deep in the tropical forests of Queensland. He recounts stories of forestry department bulldozers with their buckets hooked around strong trees on steep, remote hillsides. Operators would use the bulldozer’s winches to drag felled trees off the inaccessible slopes and onto flat ground where Frank would efficiently reduce them to 4- and 5-in.-thick slabs. Such slabs would be hoisted onto the back of his trusty Land Rover’s trailer. It was not uncommon to see this cheery German returning with his precious cargo slowly and carefully through the streets of Toowoomba. A densely packed photo album sits proudly on the bookshelf that contains all supporting evidence to these stories.

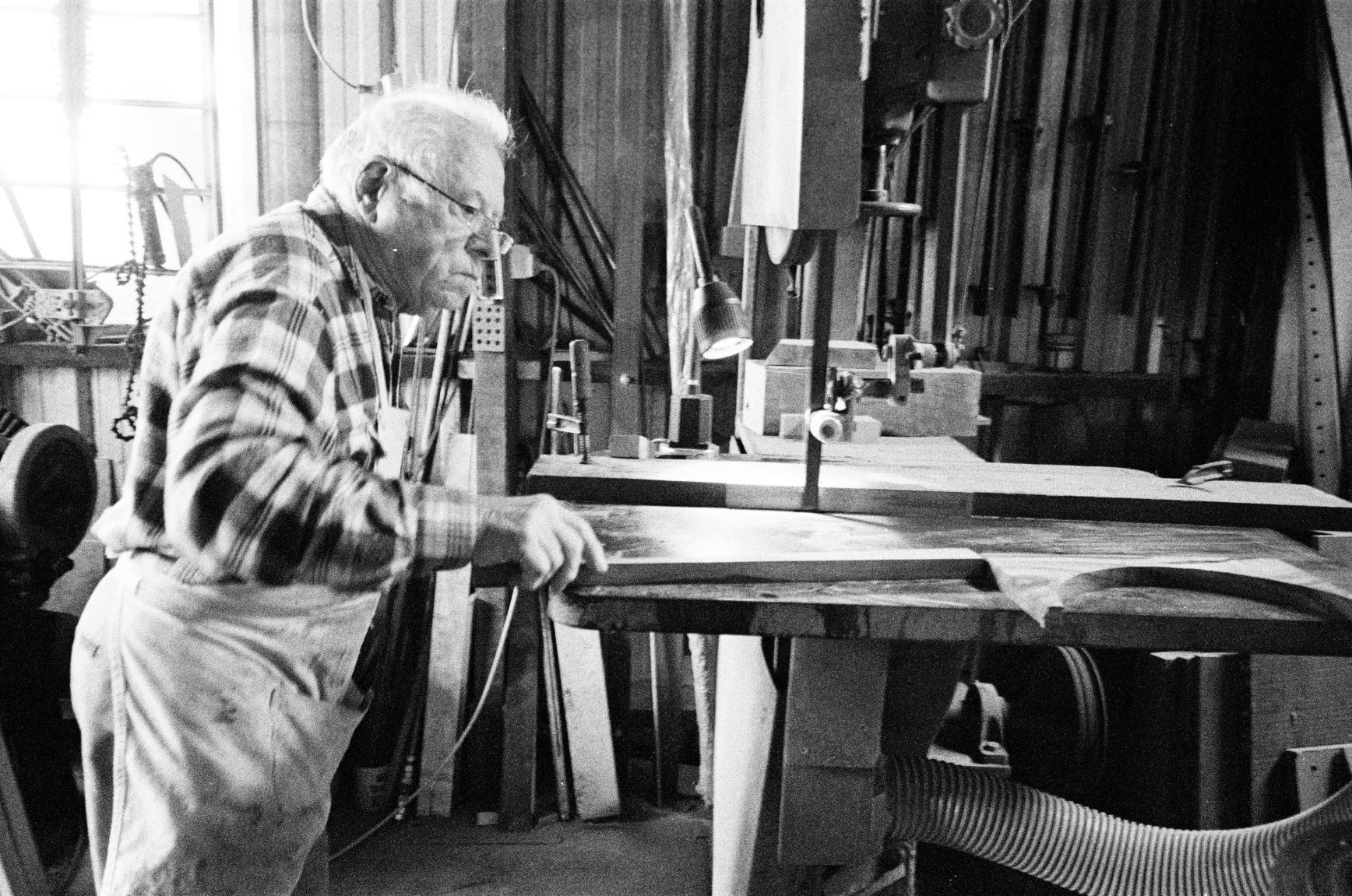

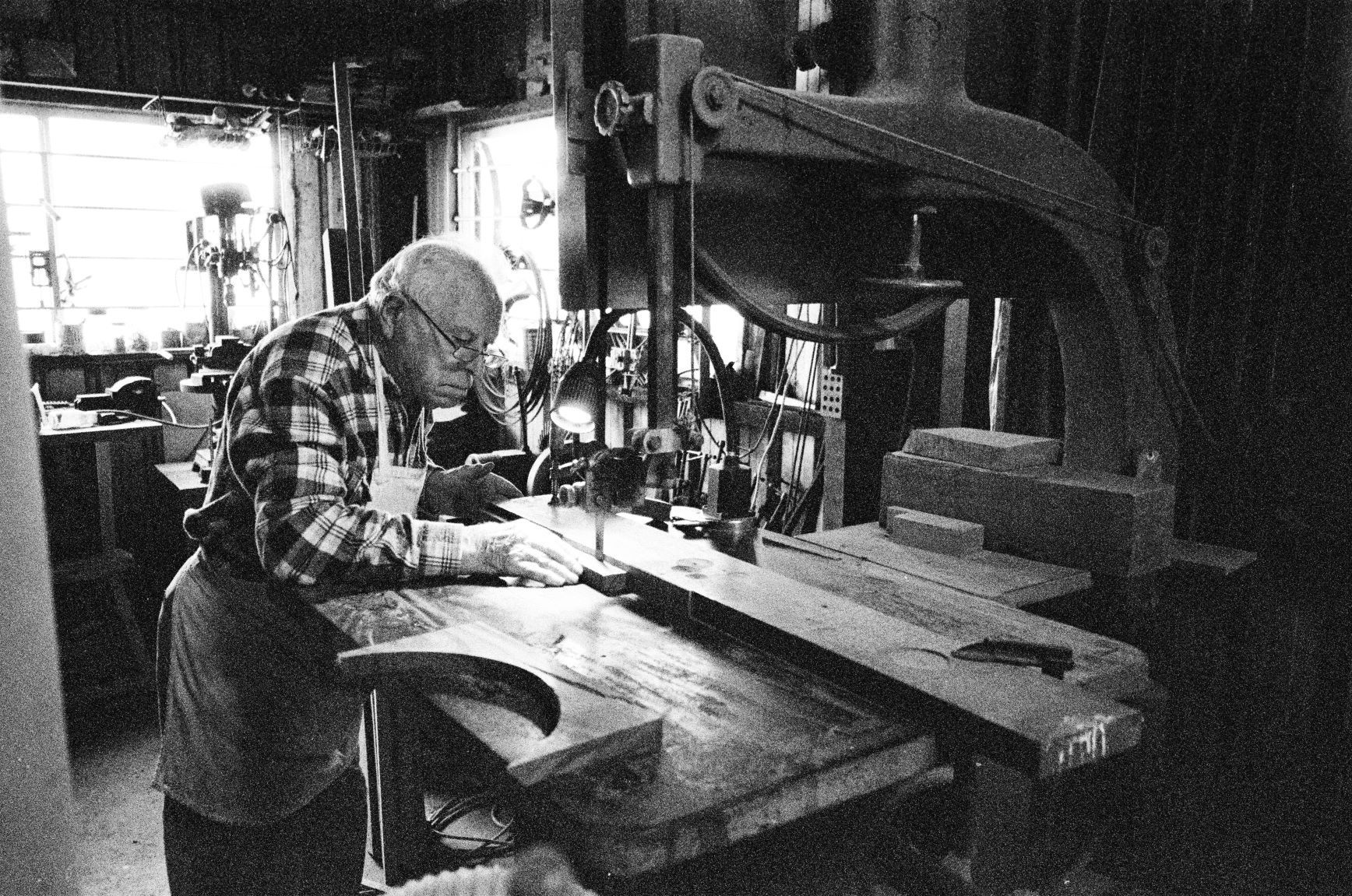

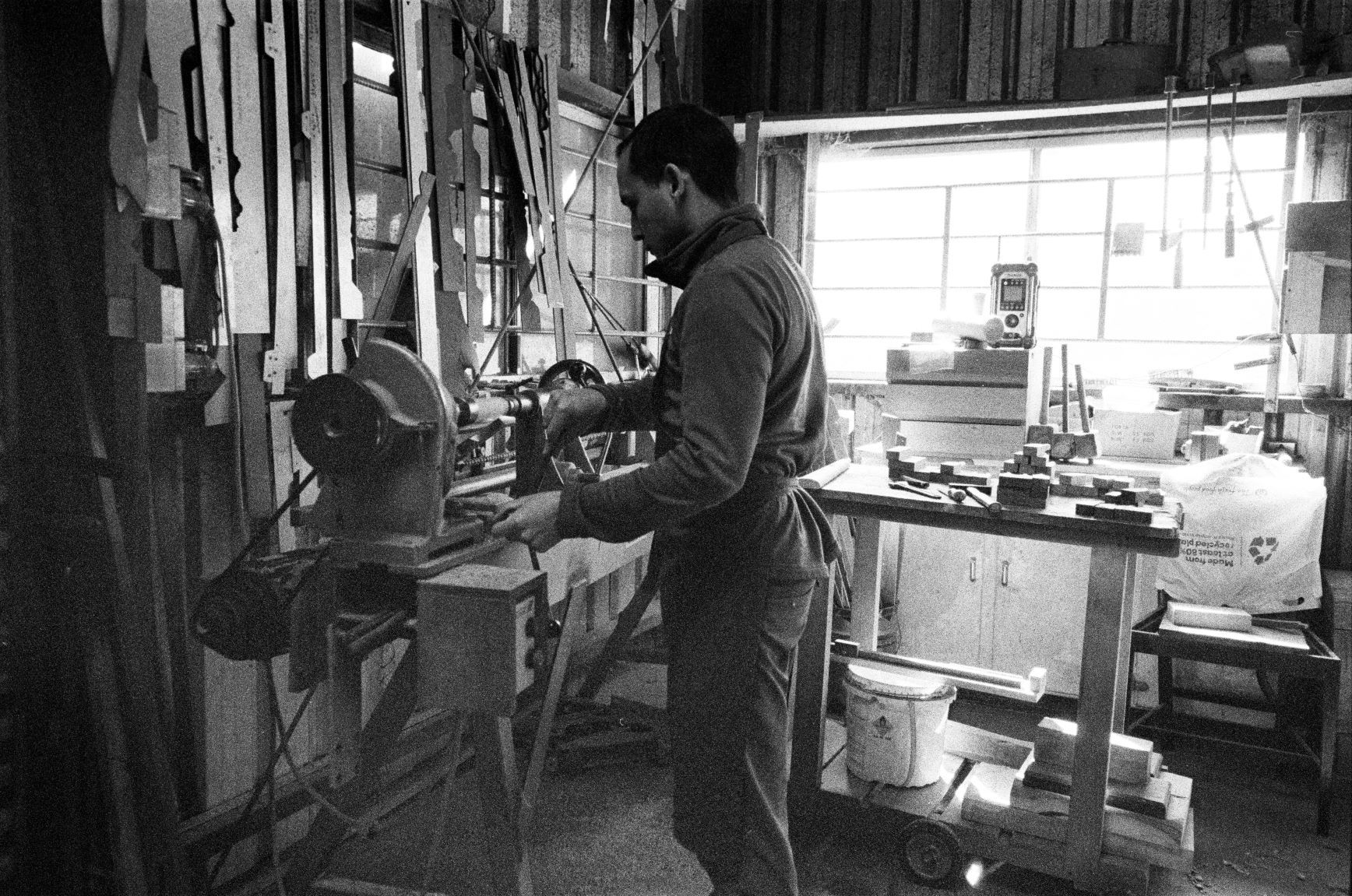

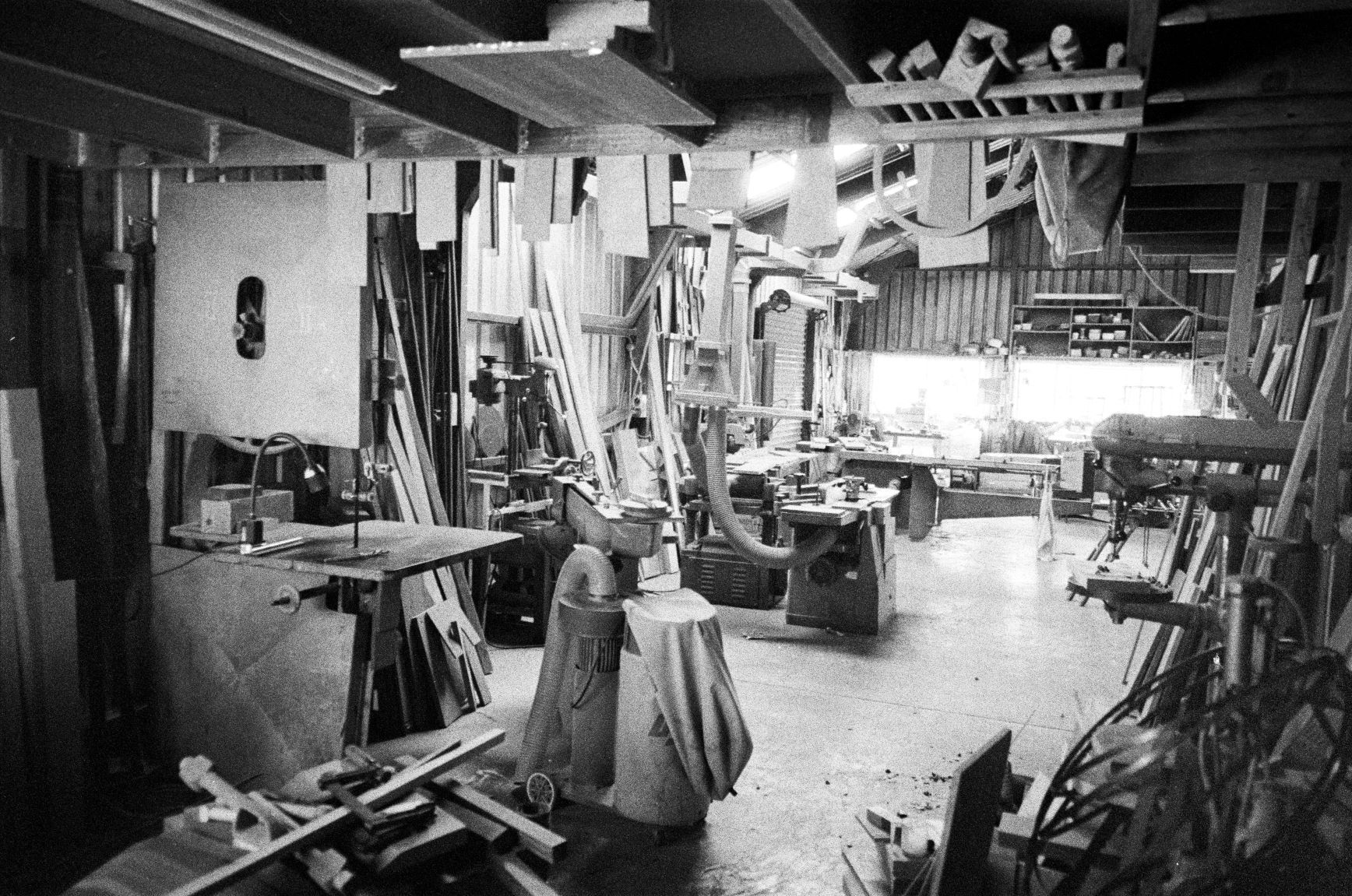

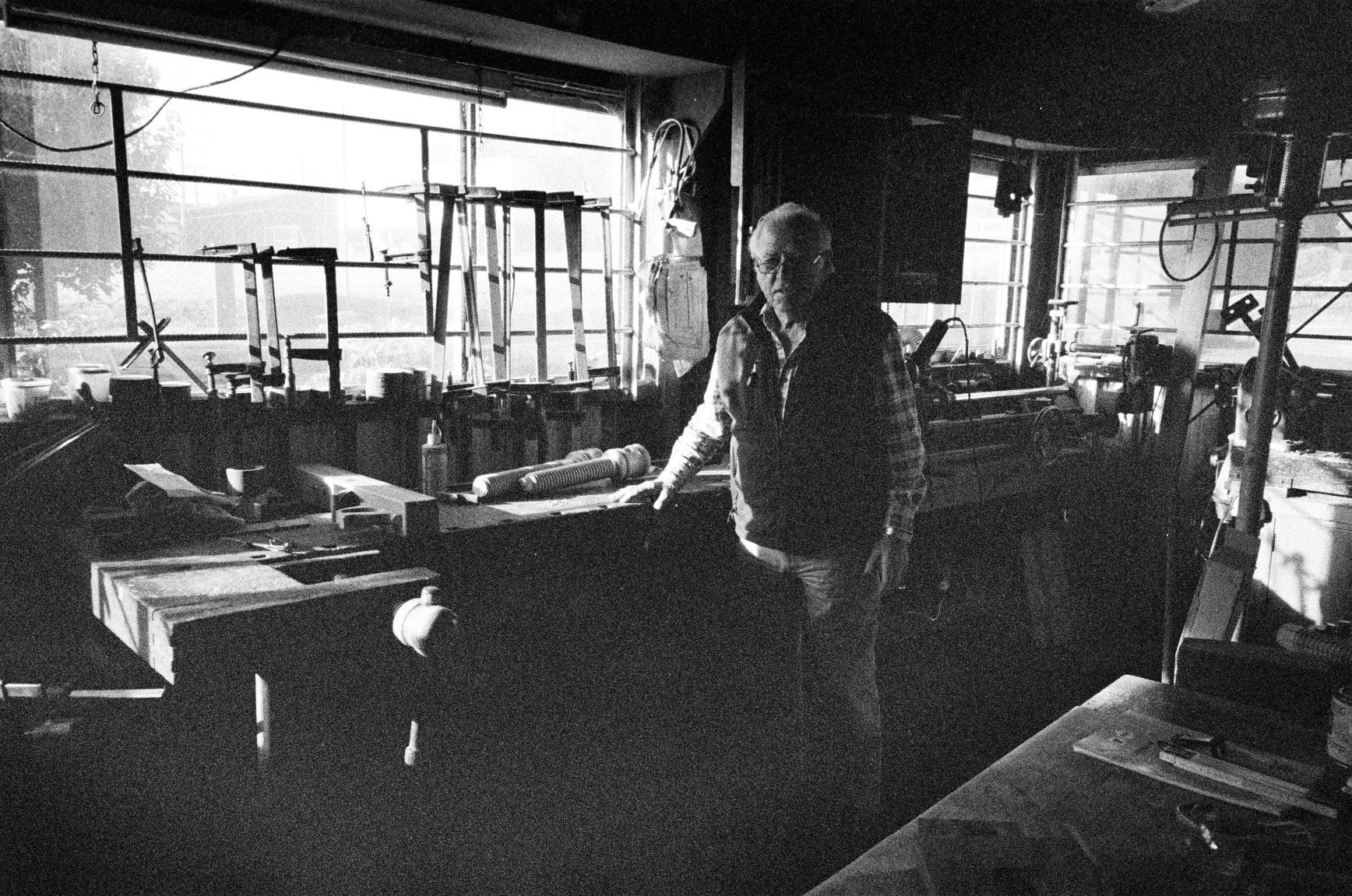

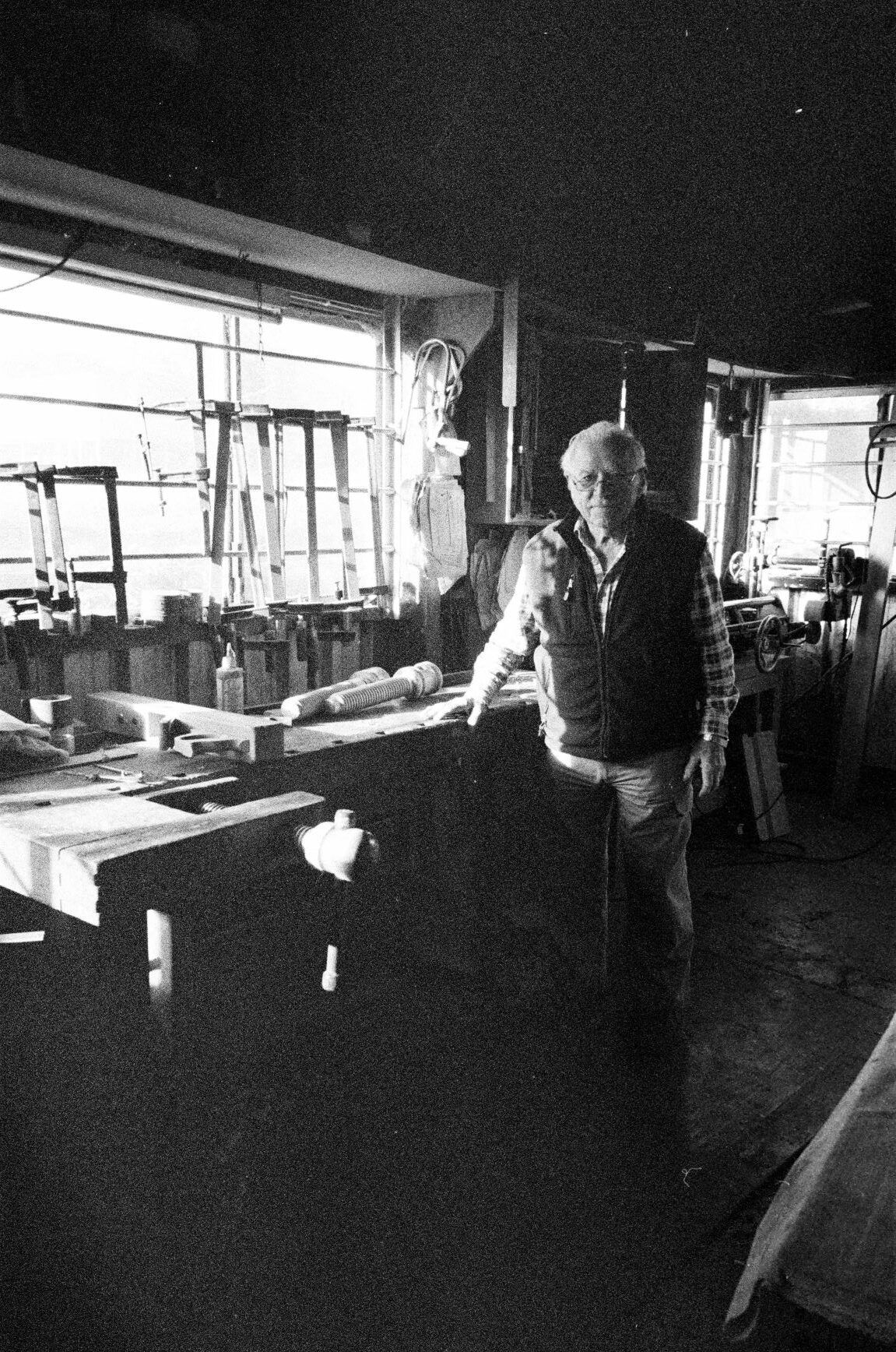

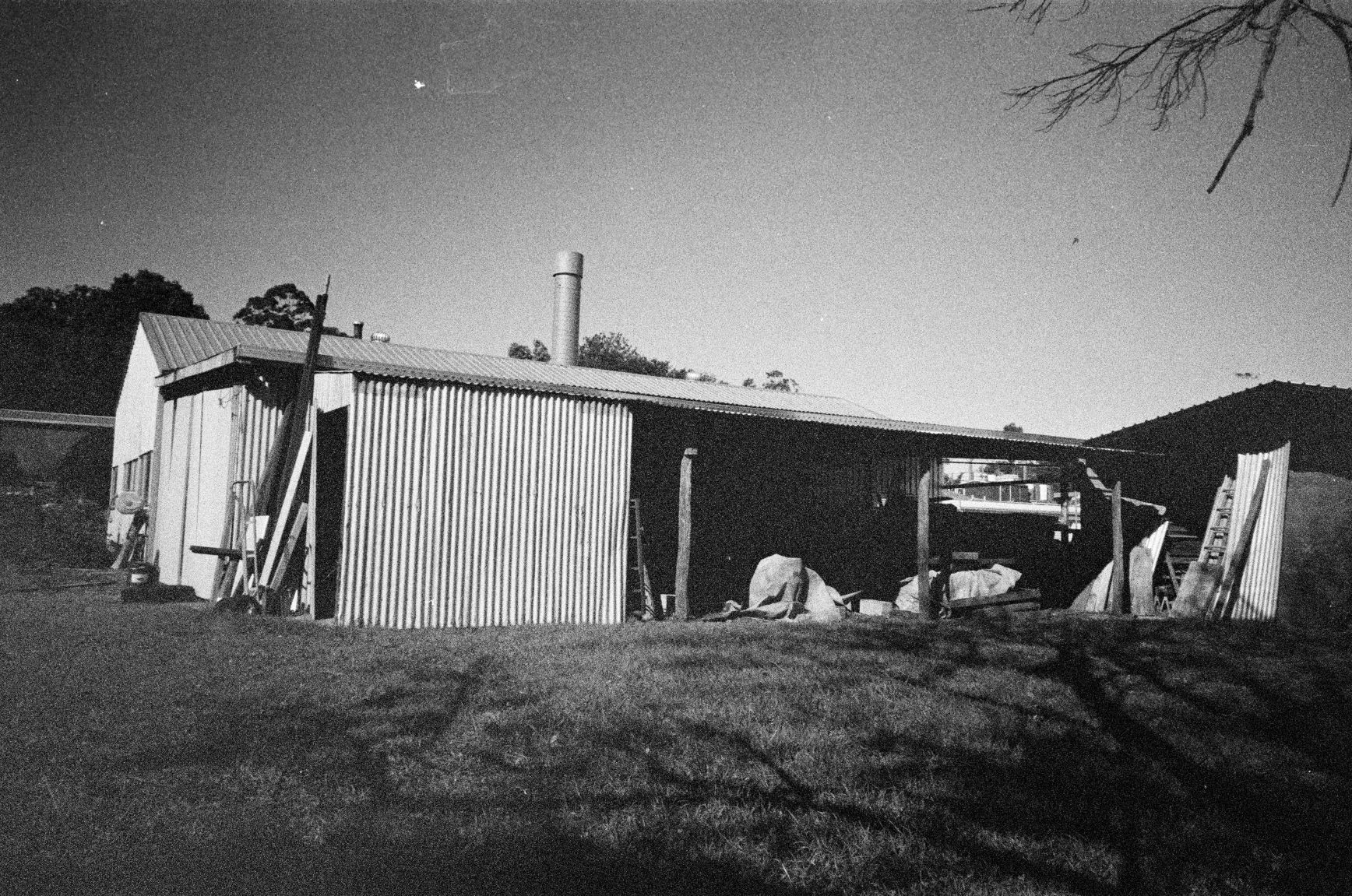

The very first day that I visited Frank, he proudly showed me his workshop, confidently proclaiming “I bet you haven’t seen anything like this!” See, Frank’s workshop is not an immaculately curated collection of machinery and collectible hand tools. Almost everything was acquired used from friends or fabricated in-house by Frank. Each has its own story to tell, and earns its keep through pure functionality. For Frank is a practical man: To discuss the beauty of design and nature over a meal or cup of tea is one thing, but in his workshop pragmatism and efficiency is prioritized above all else.

His workbench, the stalwart of the shop, is modeled on the traditional Continental workbench of yesteryear complete with shopmade wooden threads—a truly uncommon sight today. Made from the now unobtainable Satinay found only on Fraser Island, the bench bears the subtle marks of decades of use. Its Ulmia benchdogs are marred from the hammer strikes delivered to fine tune the clamping forces used to hold the thousands of furniture components that have passed through his workshop doors. Despite its appearance it retains perfect functionality; its glazed wooden vise screws possess an incomparable, delightful tactility.

With the enthusiasm of a person half his age, Frank throws up a large roller door beside his panel saw that opens into a large timber storage area built as a lean-to on his workshop. “Come on Dummkopf!” he hollers cheekily as I follow him through this maze of cellulose treasures, 6 ft. high in places.

Cedar of Lebanon, Rose Mahogany, Shining Gum, Queensland White Beech, London Plane, Red Cedar, Blackbean, Sally Wattle, Bolly Silkwood, Camphor Laurel, the list goes on. Each tree has been slabbed, stacked, and carefully seasoned for decades. To the uninitiated, it all looks the same—a mildly chaotic world of rough-cut slabs with a gray patina, the result of decades of stagnant oxidation. To Frank, it is a catalogued library of timbers. Nothing is labeled, and if unsure, a quick rub with his palm on the timber and a few long deep sniffs will give Frank the species information he needs to cut with absolute confidence.

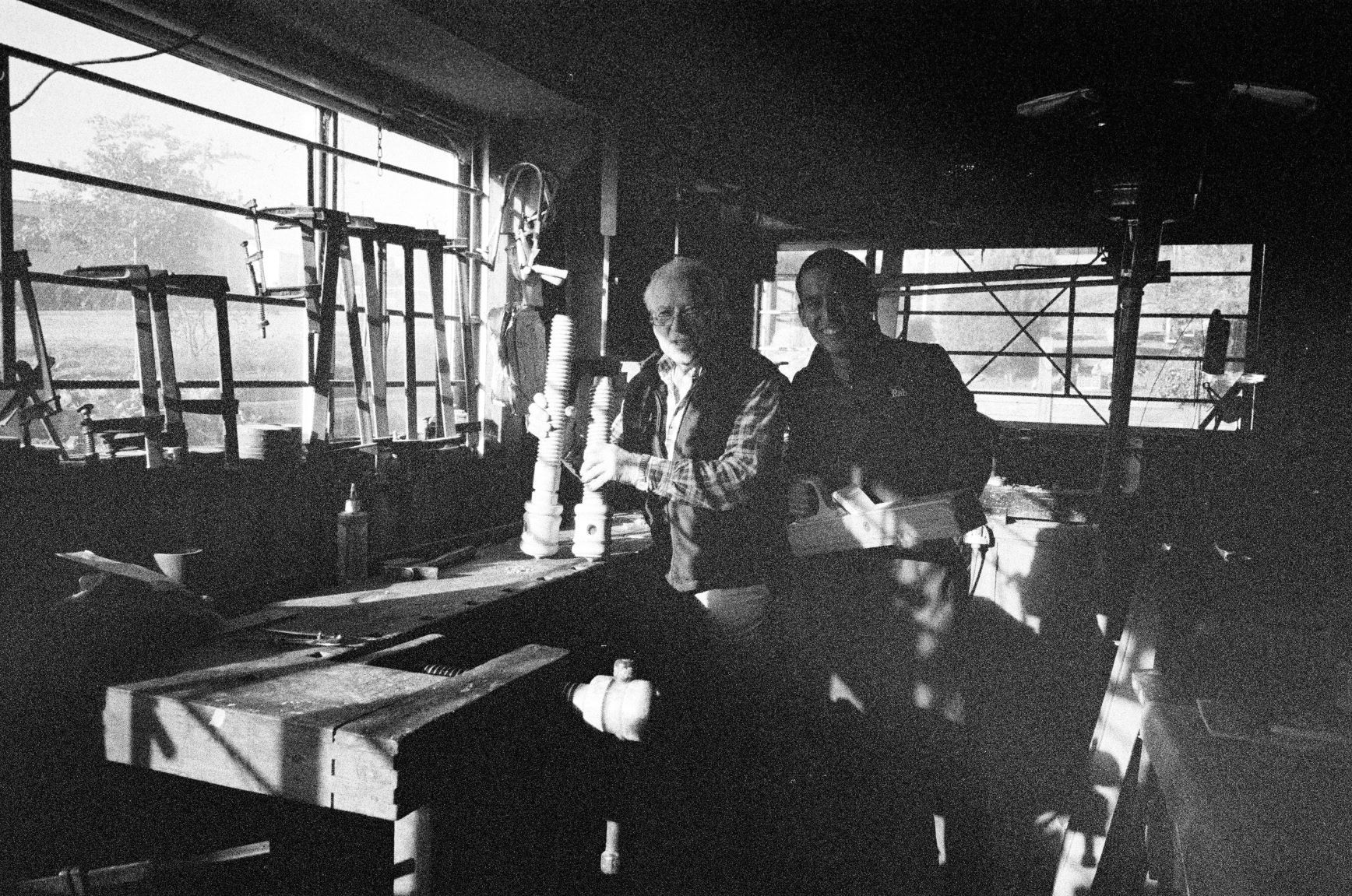

I was fortunate enough to assist in the process of producing his well-known stools—a design that won Frank awards, and is proving a consistent seller since the first ones left his workshop over three decades ago.

I was fortunate enough to assist in the process of producing his well-known stools—a design that won Frank awards, and is proving a consistent seller since the first ones left his workshop over three decades ago.

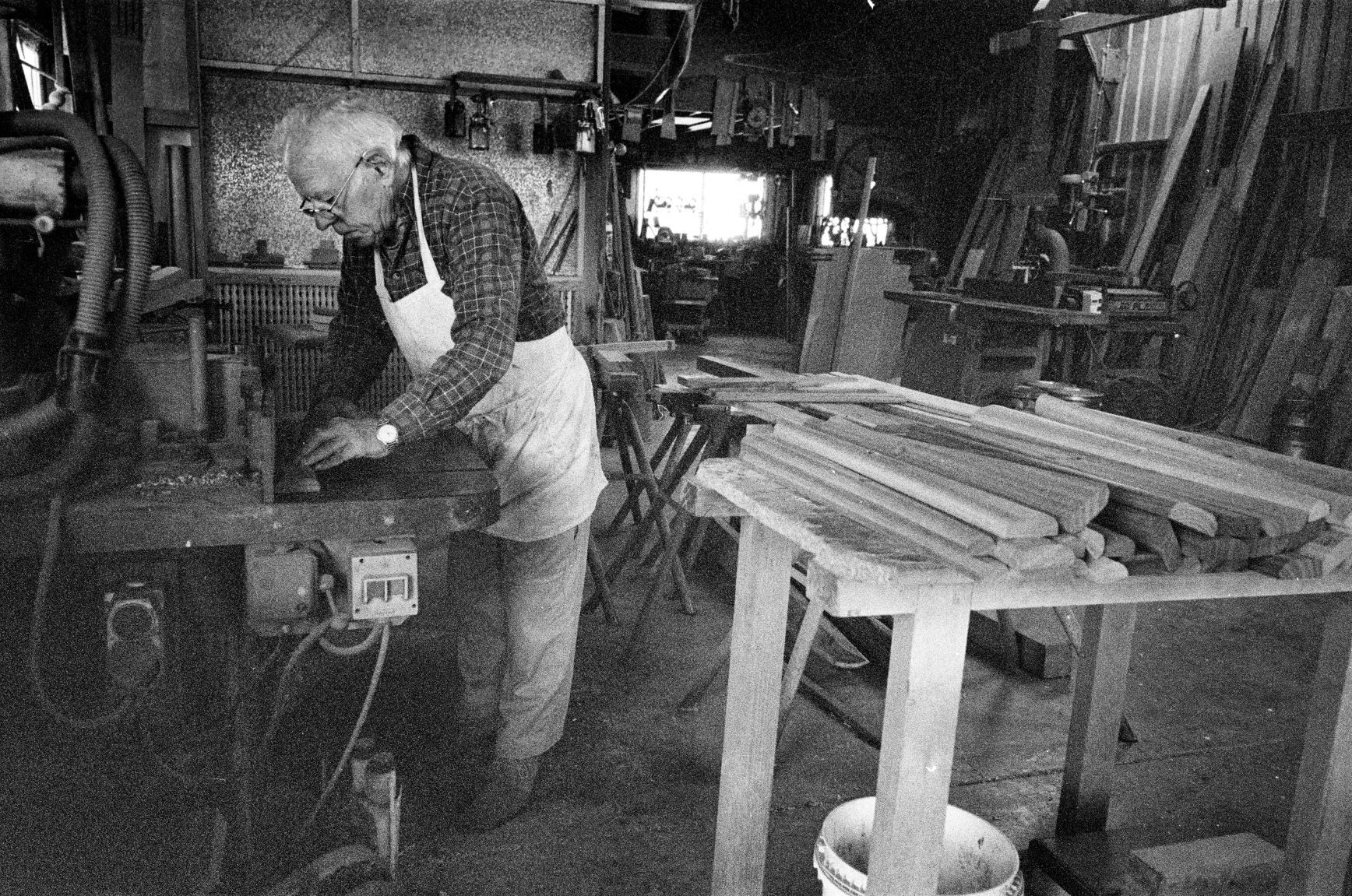

Timber is selected and carefully extracted from the stockpile with crowbars, steel tubes, and the youthful vigor of one or two enthusiastic helpers such as myself.

After being loaded onto a cart, it is brought to the front of the workshop where a chainsaw is used to reduce the brutal cuts of timber to more manageable pieces.

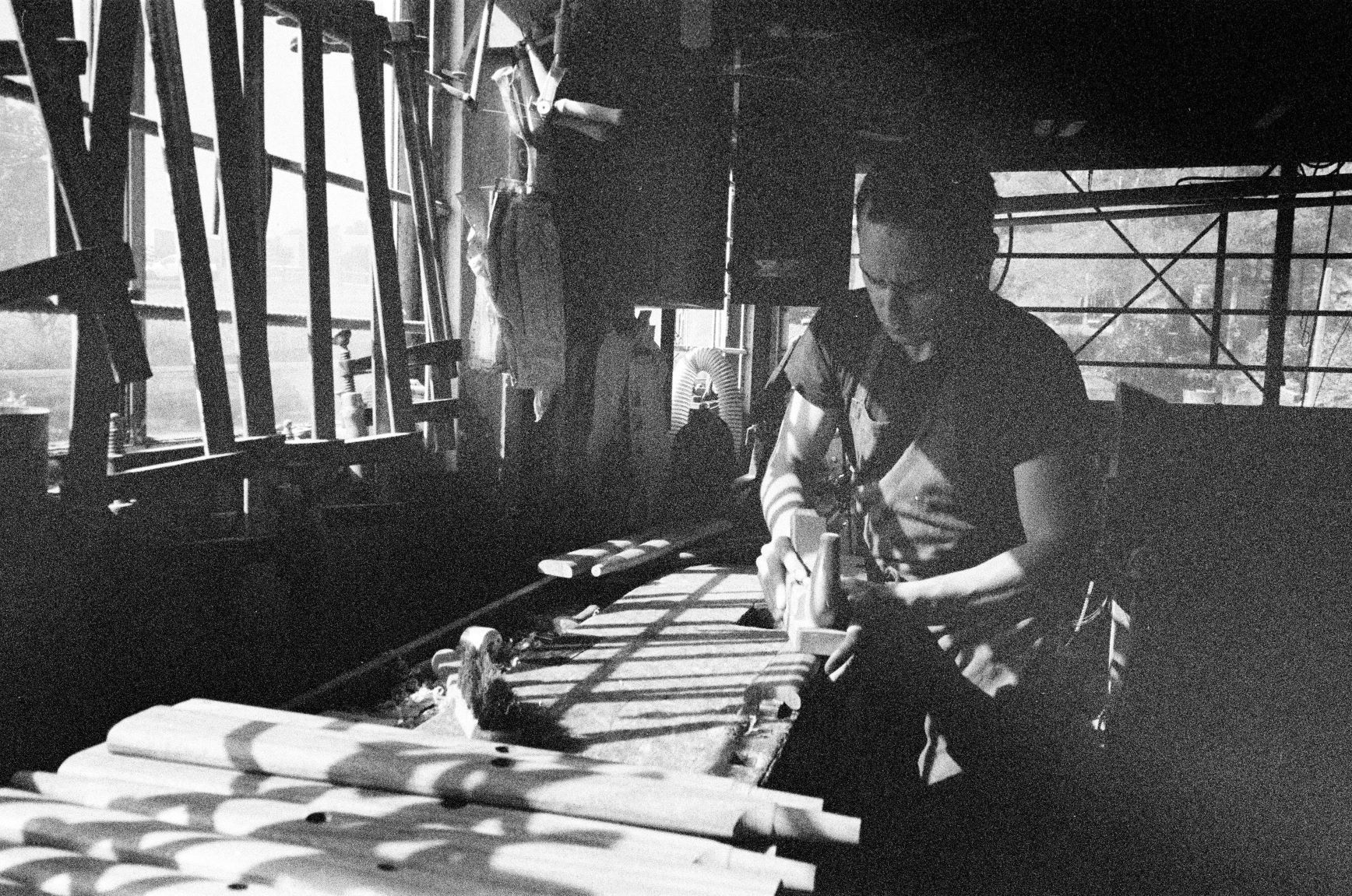

These pieces are ripped and rough milled with great efficiency before being grouped by grain, color, and cut as to what component of the stool they are most suited to. Everything is inspected, noted, and marked. After several weeks of work, what emerges is truly a thing of beauty—a three-legged stool that employs a wooden thread for height adjustment.

It may sound simple, but as a trained engineer with an eye for detail that resulted from growing up around the world-class workshops in which my father worked, I can assure you that such stools have no parallel in overall beauty and gestalt. One only needs to observe how cleanly the threads on the screw are formed—no burn or tooling marks, absolute consistency, and a design geometry that indicates the creator fully understands the mechanics involved. Frank is a craftsman foremost, and as such he leaves the subtle signatures of his hands as a reward to those who look.

To be working five or six days a week at the age of 88 with all his digits accounted for is a testament to the sharp focus and understanding of machines, tools and processes that are used in the workshop, as well as the mechanical and human limitations.

To be working five or six days a week at the age of 88 with all his digits accounted for is a testament to the sharp focus and understanding of machines, tools and processes that are used in the workshop, as well as the mechanical and human limitations.

Routine is critical. To start consistently every day with sufficient periods of rest for both mind and body is emphasized, and so a 10 a.m. “smoko” is followed by lunch at 12 and “smoko” again at 3 p.m. Recognising and never pushing the boundaries of physical and mental endurance helps to ensure safety and consistency. Adequate sustenance at each break is provided through Joan’s delicious home-baked treats washed down with ample amounts of coffee.

My father—himself an accomplished professional cabinetmaker, conservator, and craftsman—refers to Frank as “The Last Mohican,” a man who is one of the last standing in employing such methods and a living treasure because of it. Everyone that I spoke to who has met and worked with Frank agrees. Frank will never stop learning and improving. From the days I spent in the workshop working intimately together, and the lengthy discussions over many a meal, it is impossible to miss the fire and passion that Frank has to both further and pass on the craft of woodworking.

Now all we must do is prick up our ears and be humble, willing, and accepting of this gift of knowledge.

-Siegfried is a mechanical engineer based in Melbourne, Australia. He was trained in woodworking by his father – a German master cabinetmaker and conservator in the traditional approach, he focuses on combining engineering principles and thought with traditional woodworking. Siegfried hopes to shine the spotlight on the wonderful timbers unique to Australia and the unheralded craftsmen who utilise them and who have been so generous as to mentor him.

Comments

That stool is one of the most beautiful things I have seen. Also as a former machinist, I admire his DIY threadmilling setup.

@Moldmonkey, its phenomenal what he has actually made. His dust extraction system is no exception, having welded up his own blower; fan and all, and devised a filtration system that is really clever and separates the dust and chips into various sizes.

The man is honestly the quiet genius in that regard. I havnt met a woodworker who has come up with so many clever and "homebrew" solutions, most of which were done decades ago before the existence of books on jigs, the internet and forums....which makes it even more amazing!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in