Remembering a tree

No amount of setbacks or lack of resources could deter these artisans from celebrating the life of a 100+ year old willow oak tree.

When a wood artist commits to doing a “show piece” out of “special wood,” their thoughts quickly focus on designs that might relate the project to the occasion. What happens, however, when that special wood turns out to be rotten? The work of 14 wood artists in this predicament teaches us a bit about how to use marginal materials to create objects that are both beautiful and imbued with meaning.

The Lyndon House Arts Center (LHAC), established in 1973, is an important community arts center in northeast Georgia. A huge willow oak tree, between 120 and 150 years old, was a sentinel and beacon to all who visited. The tree was old, it was beautiful, and it was located on the doorstep of the Center. Sadly, the tree was cut down in 2016. Many of us have a soft spot in our hearts for majestic trees and to lose one hurts. Celebrating the tree’s life might provide some consolation.

The Exhibition

I was recruited by LHAC to curate such an exhibition. I am not a professional artist, nor am I a historian, nor am I an expert on trees. I am an avid woodworker and studio furniture maker. So, the focus was going to be on the physical remains of this storied tree, the wood. And this is what LHAC had in mind. Indeed, when the tree was cut down the wood was stored for some future use such as this exhibition.

LHAC, a community organization, was serious about supporting local artists. Happily, there are many more established artists in the area than we needed and I was able to recruit people whose work I particularly admire. Each of the artists readily agreed to make a piece using wood from the Willow Oak Tree.

The wood was rotten

It never occurred to me to worry about the wood. Surely the log had been safely stored, still intact, off the ground, and covered. Regrettably, none of these expectations were met: The log had been cut into 3- to 4-ft. sections; it was left in a field, directly on the ground, uncovered for years, and much of it was gone … poached. What was left had been affected by weather and fungi. In short, the wood was rotten and unusable for most traditional applications.

Whatever approximated usability was milled into slabs about 2-3 in.thick and 3-4 ft. in length. It still had a moisture content that was much too high to be worked. So, into the kiln. Eventually the wood was distributed. Some of us got slabs; some of us got chunks. All of us who wanted to “work the wood” got headaches. Indeed, the wood was simply unusable for a couple of artists.

The artists succeeded beautifully in their dual mission: (1) creating beautiful “showpieces” from the marginal wood; and, (2) celebrating the tree. We take up each in turn.

(Photo by Duane Paxson)

Approaches to marginal wood

Let’s start with how the artists chose to handle the marginal material they were given. I saw three approaches to the problem. The first is the “What—Me worry?” approach; the second is the “Let’s make a Deal” approach; and the third is the “Only the good” approach.

The “What—Me Worry?” approach

In the 1950s Mad magazine’s Alfred E Neuman character popularized the slogan “What –Me Worry?” suggesting that even if the world around you is crumbling don’t worry about it, just get on with things. Artists taking the “What—Me worry?” approach simply appear to care not at all about the flaws in the wood. For them, it is simply enough that what they have in their hand comes from the tree.

Perhaps the best example of this approach is the work by Duane Paxson, a longtime art instructor at Troy University in Alabama and a prolific sculptor. He “.. decided that the length of wood given [him] was a kind of “relic,” for which [he] would make a reliquary patterned after the ancient tradition of containers designed to display and to protect the sacred remains of a holy person, such as bone fragments or remnants of clothing.” Given his take on the wood there is simply no need to deal with the flaws.

(Photo L. Millard)

Larry Millard, also a sculptor and Art Professor Emeritus at the University of Georgia, was given a short branch of the Willow Oak for his project. He wants us to understand that “Not everything is what it appears to be, always look, seek… Beauty is everywhere, bask in its radiance.” For Millard, the flaws in the wood actually add to the message! Because when you open up his piece of flawed wood the radiance of the gold leaf simply hammers home the message.

Martijn van Wagtendonk, Associate Professor of Art and head of the sculpture program at the University of Georgia, has found a couple of ways to ignore the flaws in the Willow Oak Wood. He has a clock mechanism in his piece and he uses a bit of the willow oak simply as a weight to power the clock! Clearly one can ignore the flaws for this function-anything with mass would work.

Van Wagtendonk cleverly takes us down another path to not worrying about the flaws. When a tree dies it becomes timber. Under the right circumstance, with added time, the wood becomes charcoal. Charcoal is an artist’s medium. With a bit of heat, a piece of the Willow Oak , regardless of flaws, can be converted to charcoal. And that charcoal can be used to render a mural size picture of the Willow Oak tree as in van Wagtendonk’s installation piece in the show. So the wood is flawed. Who cares? The charcoal image of the tree is a remnant of the tree itself!

Alfred E Neuman is a kind of mindless looking character without a care in the world. The work of these artists is hardly mindless and is even profound in some ways. It is also interesting to note that none of these examples of “What—Me Worry?” is created by someone whose primary identity is “woodworker.” The examples are created by sculptors who frequently work in wood—not by woodworkers who sometimes do sculptural work. Indeed, I can think of no celebrated woodworker who uses rotten wood in his/her work. For these particular Willow Oak Tree artists, the compromised medium is a big part of the message.

Photo: P. Bull

The “let’s make a deal” approach

The work of several of the artists suggests that the flaws in the wood are a serious issue for them. But they are willing to tolerate them or even make the flaws into a design asset if they can find a way to meet the structural requirements of their project. The work and the rhetoric of iconic woodworkers like George Nakashima and James Krenov suggests that incorporating some “flaws” in wood such as natural edges, cracks, or spalting can often enhance a piece. Of course, Nakashima and Krenov are not dealing with wood this far gone, but they do make a persuasive case for the potential of this approach.

Peter Bull, a woodworker, a studio furniture maker, and a timber framer, writes that he was challenged to use wood “that is degrading, checking, and becoming dirt…[He stabilized] ..the rotten and bug infested areas with consolidant.” And, voila, a representation of his current work, with a top that features the Willow Oak with filled voids, cracks and the variegated color of wood in various stages of decay. Richard Shrader has been a functional artist for over 30 years. He started with wood and later added metal to his repertoire. Deciding what to remove due to rot or decay and what to leave to show the character of the wood was a challenge. He showcased a bark inclusion as the centerpiece of the book match. The flaw shows the beauty and strength of the oak. And the finish on the top is as smooth as silk. The hammered steel “tree” legs holding up the Willow Oak wood easily vie for star status.

Tom Wenzka began whittling when he was 15 and has been carving ever since. He finds inspiration from the wood itself and what he carves away is dictated by his constantly emerging image of where the piece is going and the nature of the wood itself. In this case the deal is a true partnership. Indeed, in this case, voids and partial rot in the wood help to delineate the emergent scene. Cal Logue is also a lifelong whittler and carver. While the piece he produced for this show is quite different from what Wenzka produced, the partnership in which he entered with the wood is just as striking: Logue writes “Usually I decide early-on what is to be carved, such as a woman drawing water from a well or a man hoeing weeds. But somehow the Willow had a bark of its own: an obstinate burr, meteorite print, amusement slide, and mysterious tunnel.” In this deal, the wood might actually be the senior partner.

The “Only the good” approach

A few of the artists found it difficult to realize their vision for the show without eliminating most, if not all of the rotted material. Perhaps it is fairer to say that they did their best to salvage some workable material. This is perhaps the most common approach among commercial woodworkers and furniture manufacturers.

Walt Groover had a career as a graphic designer and is now a sculptor. His wood sculptures are often cast in metal so everything about his work and its finish is meticulous. Before beginning to sculpt this piece, his wood was dried, cut into smaller pieces, dried again, then glued back together to yield the blank he actually carved. A lot of work. But the result is clearly worth it; his Guardian figure is particularly evocative. It is tempting to interpret the rectangular element ascending from the back of the carved figure. But, Groover tells me, it is there because even with all his attempts at getting only “clear” wood there was enough rot in the neck area that the rectangle was needed to secure the head!

Turning punky wood on a lathe is almost impossible. So, the two wood turners in this show opted to work on the small pieces of wood that were sound. Jim Talley has worked with wood almost all of his life. Talley turns miniatures and the blanks that he needs to work with are no more than 2 in. square. Finding sound pieces of wood that small was quite doable. And the work he is producing is astonishing. There is no scale in the photo but the vessels you are looking at are not more than 1 in. in diameter.

There is more to a Heritage Tree than its lumber

The artists had a dual mission: (1) creating beautiful “showpieces” from the marginal wood; and, (2) celebrating the tree. So far, we have talked a lot about wood and its problems. But our connection to trees is much more than the lumber they produce. So how did these artists celebrate/memorialize the tree? Each piece contained at least some of the wood from the tree. So, each piece, by requirement, is a kind of reincarnation of the tree, a way of giving the tree a new and different life. But most of the artists went further than that.

There were a couple of idiosyncratic ways of memorializing the tree. Under the assumption that the Heritage tree deserves to be remembered simply for what it was, Duane Paxson directly proceeded to create an elaborate memorial to the tree with his Willow Oak Tree Reliquary. And, my music stand stands as a “meta-celebration” of the tree by celebrating the artists that celebrate the tree!

There were also three common ways in which the artists drew our attention to the tree. Some artists celebrated the tree through what may be termed “iconic resurrection,” creating a piece that bears some visual resemblance to the tree. Other artists focused on the tree’s age and its status as a silent witness to history. Finally, some artists focused on the internal beauty or character of Heritage trees.

Iconic resurrections

Five out of the 14 pieces incorporate imagery of the tree itself as a way to celebrate the tree. The largest, most realistic rendition of the tree’s image is Martijn van Wagtendonk’s charcoal mural. A likeness of the tree is also resurrected in three dimensions as each of the legs in Richard Shrader’s wonderful Willow Oak Coffee Table. When we recall that the charcoal for the mural was produced by firing the wood and that a forge was used in producing the hammered iron trees, it is difficult to avoid the ironic thought that these pieces have been through “hell” in their journey to resurrection.

Leonard Piha is a retired art teacher and a prolific sculptor often using discarded and found materials in his work. His Tinker Man is, at the same time, a human figure and an iconic resurrection of the Willow oak tree. If you look closely, the engravings on the arms are branches and the facial features are leaves and the trunk of the tree is on the trunk of the man. I will have more to say about Piha’s piece below.

My own piece, When Art Grows on Trees, Music Stand, is both a 2 dimensional and 3 dimensional iconic resurrection of the tree. The 2 dimensional image on the tray shows the canopy of a Willow Oak Tree with works of many of the show artists as the “fruit of the tree”. And the 3d stand holding the tray is made in the shape of a tree. This piece pays homage to both the tree and the artists participating in the Exhibition. Finally, a close look at Tom Wenzka’s piece also reveals iconic resurrection imagery including willow oak leaves and branching.

It is not surprising that a common way of memorializing something concrete that is gone is to produce an image of it. And that strategy seems effective—many of us carry photos or other images of people, places or things that matter to us. Those images are useful in triggering memories of the object and many of the feelings associated with it. So, we easily understand the strategy and take a bit of joy in the variety of iconography across artists.

Focusing on history and the passage of time

The Willow Oak Tree lived a long time and it had a history. Fully a third of the artists chose to capture this abstract, temporal dimension of the tree in the work they produced.

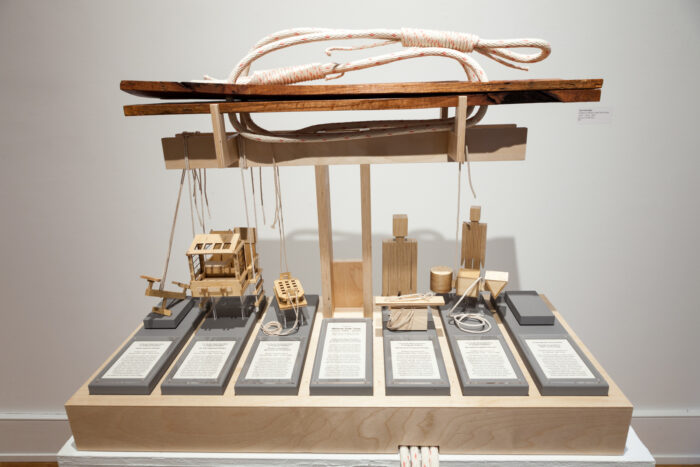

Tad Gloeckler is an architect. He has a background in conservation, and is currently Professor of Art at UGA. He views the tree as having a history of human interaction and as a marker for changes in architectural design over its lifetime. A favorite human pastime with a tree is swinging and Gloeckler uses swings to allude to the human connection. The “canopy” for his piece is a Willow Oak swing (including ropes for hanging). Below are smaller swings built in a variety of architectural styles that had and have come into fashion during the lifetime of the tree, i.e., from “Dada” circa 1918 to “CNC Technology” 2016. In his piece we can literally see art history concretely unfolding.

History is not just names and dates. It also has a subjective side. A smell, a nursery rhyme, sights from our childhood can generate personal feelings that also connect us to the past. Leonard Piha’s Tinker Man is an allusion to a non-fictional historical character who “… allows the viewer to travel down their own memory lane. For example: the trunk = traveling, hanging tin objects = “oh, my grandma use to have one of those,” the memory of someone coming to your house and sharpening knives or fixing pans, and the open arms hinting that everyone has their own private feelings about religion.” My own memory of a tinker man gives me a deeper appreciation of this multifaceted work.

History has little meaning without the concept of time. All of us understand clocks and other devices that count regular intervals to measure the passage of time. And three of our artists celebrate the Willow Oak by creating pieces that depict ways of measuring time. We have already seen van Wagtendonk’s clock with a piece of the Willow Oak as the driving weight. Reid McAllister is a sculptor who uses whatever materials are at hand for his assemblages. His Time Machine appears to be an abstract rendition of a clock. The piece “.. is an expressive, metaphorical piece meant to honor the life, times, and beauty of the beloved Willow Oak.” Jim Underwood is a skilled wood turner specializing in pyrography. His hourglass, titled “Turning Time” also memorializes the Willow Oak by alluding to the passage of time.

Focus on the internal character

Four of the artists celebrated the tree by focusing on its “inner beauty” or putative character. For example, Larry Millard gilded the inside of a branch of the tree to call our attention to the inner glow of the tree. Peter Bull and Richard Shrader were more concrete and quite explicit in calling our attention to the inner beauty of the tree by using the “innards” of the tree as the top and a major focal point of their tables. Finally, Walt Groover transported the Willow Oak’s character as a “… protector of the ideals and culture of the Lyndon House.” into a muscular human figure in his Guardian.

So that’s the exhibit

A tree stood among us for more than 120 years. Its presence was important enough to organize a way to celebrate/memorialize that presence. Fourteen artists, using compromised wood from the tree, created pieces that help memorialize and celebrate the tree.

The work of the artists and the less visible work of mounting the exhibit has led to a few observations. On the face of it, a show about a dead tree does not seem particularly sexy. The tree was old and large but not a record breaker in either dimension. Nevertheless, the idea of doing a show about the tree was adopted with unanimous enthusiasm; recruiting artists and donors for the show was extraordinarily easy. And, in spite of the pall cast by COVID, the exhibition has been among the more popular ones at LHAC. It appears that trees do have a special place in our hearts.

This show relied on artists from a limited geographic area and it specified the medium, i.e. wood, and the message, i.e., a single tree. Given these restrictions, the high level of variability among the pieces is noteworthy. I have outlined the varied approaches to using the compromised wood, and also discussed some of the variations in how the artists celebrated the tree. The pieces also showed variability in size, in functionality, and in abstractness. The restrictions provide coherence but the hearts and the hands of the individual artists provide more than enough surprises to maintain interest.

I am taken by the extent to which the material influenced the nature of the pieces. The materials had a large influence not only on the physical attributes of the pieces but also on how the artists remembered the tree. For example, when entering the gallery, perhaps the most salient piece is van Wagtendonk’s charcoal mural. The idea of an iconic representation of the tree only occurred after he thought about converting the wood into charcoal. Similarly, Paxson’s idea of the reliquary came only with the realization the material was literally a rotted remnant. Before becoming involved in this show I wondered if fine woodworking is possible with awful wood. Now, as I contemplate the interplay of the state of the material and the work produced, the answer is a resounding, YES.

|

|

|

Trees trained to grow into furniture |

|

New life for old wood |

Comments

What a fascinating article. I live near Atlanta but have never heard of the Lyndon House Arts Center, it's probably less than a 2 hour drive from me.

The creative solutions they devised for celebrating the tree are simply mind blowing. I think my favorite was turning some of the wood into charcoal and then using it for the large tree illustration.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in