Rabbeting a Shelf for Strength vs. Appearance

When rabbeting a shelf to fit into a dado, is it better to put the rabbet on the top or the bottom?

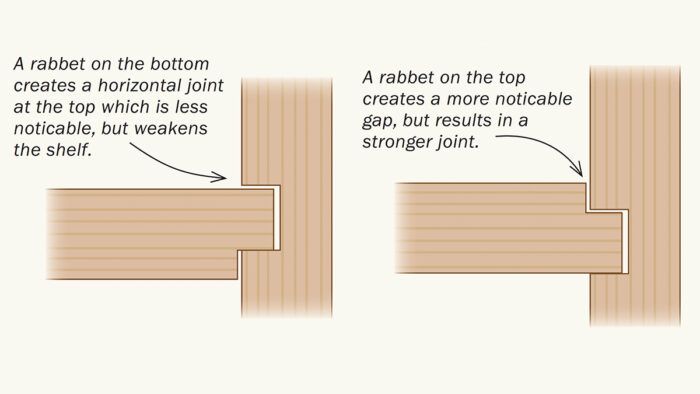

In most of the plans where I see edges rabbeted to fit into dadoes, the piece is installed with the rabbet underneath. I grant that this avoids any risk of a gap appearing if the rabbet doesn’t seat fully either during construction or due to wood movement later, and if this is the bottom of a box it lets you make the bottom flush with the bottom of the sides while being stronger than simply setting the bottom into a rabbet on the sides.

But it seems to me that this orientation does not produce the strongest joint. Forces from above could theoretically split the fibers leading into the tongue away from the rest of the board.

If we invert this arrangement and rabbet the top of the board, weight on the board presses the tongue inward rather than pulling it outward. Now you would have to break the fibers leading into the tongue to make the joint fail, not just split the piece along its grain… and it should be able to bear significantly more weight as a result.

I know, wood is surprisingly strong stuff, so the cosmetic concerns may be more important in fine furniture. But if you’re building something that will be heavily loaded such as workshop cabinets, “upside down” might be the way to go. Am I wrong? Am I just overthinking this? I presume folks like the UW Forest Products Lab have already run this experiment and could tell us.

—Joseph Kesselman, Arlington, Mass.

Like many things in woodworking, the answer is that it depends. You are correct that when you face the rabbet up, the joint is stronger, for exactly the reasons you outline. On the other hand, any potential chipping or gaps are more obvious, from the perspective of a viewer, who is, in effect, looking down into a vertical joint. With the rabbet facing down, the joint is less conspicuous and easy to pull off without visible gaps. That’s because you are looking down on a horizontal joint. However, as you point out, the joint is also a bit weaker that way. The best woodworkers will consider all of these factors when choosing which way to orient the rabbet.

—Asa Christiana, Workshop Tips editor

More like this

|

All About Rabbet and Dado Joints |

|

Handwork: Three Ways to Cut a Rabbet Joint |

|

A dark horse of cutting rabbets by hand |

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Pfiel Chip Carving Knife

Marking knife: Hock Double-Bevel Violin Knife, 3/4 in.

Leigh Super 18 Jig

Comments

But, why rabbet the shelf at all? One way weakens the shelf a little; the other way weakens it a little more.

Why not just dado the vertical piece to the full width of the shelf? There would be no gap visible when looking down.

Is there any advantage to rabbeting the shelf?

TT

I have the same question.

If you were working using only hand tools and in particular a dado plane which can only make a single fixed width dado, it was common to rabbet the shelf stock to fit the dado. Easier than planing down the stock to an exact fit.

Using power tools such as dado stacks and powered routers with various collars and jigs means you can usually make the dado to fit the stock.

There are many ways to attack the problem depending on tools at hand.

The joint is basically as strong either way you put the rabbet. If it is a loaded shelf, the force transfers through the same depth of material either way it is cut. The shear force is the same going through the same material. The shelf could hold a little more weight if the rabbet was on the bottom, if you look at bending force because the tiny shoulder helps against compression.

The question is, again, why rabbet the shelf at all?

Mr. Purdue goes into an engineering analysis of the shelf (but does not comment on the splitting danger of a bottom rabbet). But even that strength analysis tells us that a no-rabbet shelf is a tiny bit stronger.

So, both aesthetics and strength favor not rabbeting the shelf, but dado-ing the vertical part to the full width of the shelf.

Why rabbet the shelf?

The reason for the rabbet has more to do with making the dado. Most people use a router and straight edge to cut the dado. 1/2" spiral or straight bits are ussually used. After cutting the dado a rabbet has to be cut on the shelf so it will fit in the 1/2" wide dado.

So a 3/4" router bit is a rarity? I did not know that.

If you half the width of the dado, you half the amount of cross grain area. Meaning that the issue of wood movement creating an imperfect fit has been reduced by half.

In modern times, that seems to me the predominant reason for a rabet. Wood movement is still the same in the machine age. (maybe even more so due to central heating) ;-)

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in