STL262: The old tool trinity

Vic, Mike, and Ben discuss old machines, professional woodworking, milling, and accuracy.Sponsored by the Northwest Woodworking Studio’s Online Mastery Program

Check out Bill Pavlak’s blog here:

|

New shops and old moviesHow do we decide what’s important in our workspaces, what’s too much, and what’s not enough? |

|

The power of the hobbyistMany believe hobbyist woodworkers couldn’t possibly be as good, fast, and talented as pros, but Vic Tesolin argues this is a silly notion. |

Question 1:

From Tim:

When milling up stock for a project, I follow the standard procedure of first jointing one face which is then used as the reference face when sending it through the planer to bring the opposite face parallel and to final thickness. It’s common for me to work with stock wider than my 6” jointer, and I have become comfortable getting the first face free of significant twist, bow, or cup with handplanes, then using that as my reference surface as I feed it through my 13” planer. With the opposite face now planed true, I continue to follow the usual step of flipping it over and sending it back through the planer to refine the original hand-planed face.

My question: How close to perfect does the initial handplaned reference surface need to be before sending it through the planer? I’ve read in a couple of places that it only has to be “reasonably close” to flat, but I don’t know what that means and find myself getting pretty obsessive and spending quite a bit of time with the original handplane work. Am I overdoing it?

|

Squaring Up Rough LumberLearn the four-square technique for milling lumber |

|

Which first, jointer or planer?It’s a tough question. Vic Tesolin argues that if you’re armed with a jack plane, the answer is obvious. |

Question 2:

From Aaron:

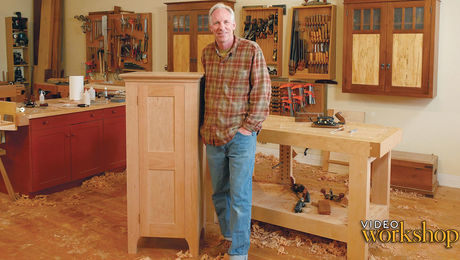

I’m making a few small boxes with dovetail joints, but I’m really struggling with the thin material (about 1/4″) and the small size of everything. Things tend to chip out more than in thicker wood while sawing or paring, my tools are disproportionately large, and any mistake is amplified by the small size of the finished product. Are there any tricks to make this easier, or do I just have to get better? For what it’s worth, I’m following the instructions from Chris Gochnour’s 2018 video workshop on FWW.

|

VIDEO WORKSHOPEnfield Cupboard with Hand Tools featuring Chris Gochnour |

Smooth Moves:

Ben: Being off by a degree when drilling mortises for a furniture repair

Vic: Not checking the depth on his tracksaw before plunging

Mike: Not realizing that his really cool clamp can be used on his bench

Question 3:

From Matt:

I struggle with milling and cross cutting. Every time I crosscut something on my table saw I spend 30 minutes trying to get my miter gauge or sled to give me a result that I consider acceptable. I have a unisaw and use an incra 1000se with a wood worker 2. I have done my best to ensure there is no play in the miter slots. Using the woodpeckers saw gauge 2.0 I have gotten my slots parallel to the blade within about .001 of an inch. There is a little run out but, it is within .002″. On an 8″ cut I usually end up giving up once I get to about .001-.003 from square (on a 12″ starrett combo). I spend more time trying to calibrate my equipment than I do using it. Would you consider these results acceptable, or should I keep searching for the perfect cut? Would a dedicated crosscut blade serve me better? I hate gappy joints… it would be nice to just cut something.

Milling can also be bothersome but at least it makes sense when I get less than perfect results. What do you guys consider “flat”? When do you guys decide it is good enough? .001″ doesn’t sound like a lot but as the inaccuracies pile up and compound over the course of a project, I often find myself unhappy with the end result. There are plenty of conversations that declare you need to be flat and square but there is very little description of what those terms mean to the pros.

Every two weeks, a team of Fine Woodworking staffers answers questions from readers on Shop Talk Live, Fine Woodworking‘s biweekly podcast. Send your woodworking questions to shoptalk@taunton.com for consideration in the regular broadcast! Our continued existence relies upon listener support. So if you enjoy the show, be sure to leave us a five-star rating and maybe even a nice comment on our iTunes page.

Comments

Hey Ben, You need to be careful learning how to pronounce words from Vic. He gives you the Canadian pronounciation, and that only works if you speak metric.

Bob

Mine is a flip phone, but I love you Guys together

Joe

re: Question 3

One thousandth of an inch over 12" is more than flat enough and square enough for anything in woodworking.

We need to remember that the material itself is moisture dynamic, and is going to be moving much more than that 1000th of an inch, often before we even have a chance to glue it up. Of course, it will move more than that after you glue it up as well. This is where project design comes in to play, and an awareness of materials. Remember, many pieces of woodworking that are still revered and looked at with awe to this day were made with tolerances nowhere near what you are describing.

If you want to be a machinist, sure, go ahead and spend all your time trying to calibrate your machines to the point where they can perform with under 1000th of an inch accuracy. But if you want to be a woodworker, learn when good enough is good enough with the machines and then do the woodworking that you want to do.

By the time your woodworking projects have been through two years of seasonal changes in heat and humidity, that 1000th of an inch difference isn't going to matter.

A few words on the machine rehab trinity. I have the band saw pictured there. A Walker Turner 16". Probably from the 1930s or 40s ( I believe ). A great machine. I would qualify the general theory that you need all three elements for a successful rehab. Yes you need to know what you are doing mechanically,but time and money are variable. Many of us, have more time than money or vise versa. Being the scavengers we woodworkers are we find ways around the limitations of time and money and are still able to complete a successful project. I would urge anyone who has an opportunity to get a machine of that vintage at a reasonable price to go for it and if it takes more time or money than you thought , be patient. If you don't have the mechanical ability it will be a good learning experience. No one is born knowing how to repair machinery, ask questions and move forward.

Proxxon Tools are very high quality. But for the best modelling table saw and thickness sander (Ben, take note of the luthier version) check out Jim Byrnes Machines at:

https://www.byrnesmodelmachines.com/

I've always wondered why people who enjoy kumiko don't all have a Byrnes saw.

Mike, I enjoyed your recommendation at the end. If you've ever seen a video of an arctic fox, they jump about 12 feet in the air in order to bury their nose as deeply as possible into the snowy tundra. This is all in the faint hope of perhaps nailing a tasty morsel. You are the Google equivalent of an arctic fox, and now you know everything there is to know about the world of professional Frisbee golf. I know it's not true, but the image entertains me.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in