Benchmarks: Kevin Kauffunger—Inspired by the creativity in our craft

I don’t remember when I first heard of Fine Woodworking, but it changed my life. I was a rudderless teenager in the early 1990s in Pittsburgh, Pa. I was arty or “art adjacent,” meaning that I loved art class and when I skipped school, I’d often end up at the Carnegie Museum of Art, checking out the De Buffets, the Warhols, the De Stijl furniture. I loved the fine art of “masters,” but for my own creative work I struggled with its seeming lack of utility – what’s the point? At this time I was also surrounded by carpenters—my neighbors, my brothers, my family history that went back generations. To make a buck I started working construction on old homes in the city. I was more a schlepper than a carpenter: busting out old plaster walls, slinging impossibly heavy buckets loaded with debris on my back and carrying them down three flights of stairs to a dumpster, scraping, pulling, priming, sanding … whatever needed to be done. I didn’t love the work. I did love the material, the craftsmanship of the old buildings, and the physicality of the job. I loved the construction—the sculptural aspect of buildings and their utility. At the lumberyards I’d see copies of Fine Homebuilding and Fine Woodworking that shed an aspirational ray of light that building could be done on a higher plane, that form and function could be one.

After high school I went to college. Academics weren’t my strength, but the open access to the art school’s woodshop was awesome. How sweet it was to build in a controlled environment without the dirt and grime and backbreaking labor that I had known as a schlepper. At the library I’d avoid my course work on game theory or macroeconomics by burying myself in the latest Fine Woodworking. The precision of the work was inspiring. The how-to instructions with their amazing illustrations were great, but the back page and Readers Gallery were my jam. These folks were doing it—making art that had purpose, utility.

If you stay in college long enough you will graduate, but you may not be interested in a career doing what you studied. I went back to Pittsburgh and latched on to a small three-person shop that made windows and doors for old homes. I put in thousands of hours under the low focused hum of machines processing roughsawn Spanish cedar and white oak into beautiful windows and doors. I learned how to expertly use jointers, chain mortisers, hollow-chisel mortisers, single end tenoners, planers, radial arm saws, straightline ripsaws, shapers, routers, and bandsaws. I got a subscription to Fine Woodworking, reading each edition cover to cover. I saved money and acquired some small machines of my own. My future father-in-law gave me access to a one-car garage to set up shop. In the evenings I started building furniture. Bad furniture at first, followed by OK furniture. You have to start somewhere.

There was a common thread among the Gallery work that most appealed to me—many of the makers were graduates of the College of the Redwoods Fine Furniture program (now The Krenov School). I knew nothing of James Krenov, or the school that he built with Michael Burns, David Welter, and others. I’d never been on the West Coast. I only knew that the College of the Redwoods produced great makers. That was enough. I loaded everything that I had into my Ford Explorer. The suspension sagged across the country to Northern California. For nine months, the school and its community gave the gift of intensely and singularly focusing on craft. I radically improved as a maker. Everyone did. You could not help it. It wasn’t just about developing woodworking techniques; it was equally about developing an intense thoughtfulness and care toward the work.

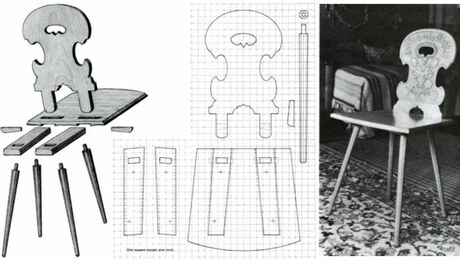

I returned to Pittsburgh when it was over. I kept building. I got a piece on the back cover of Fine Woodworking. In time I realized that my passion for woodworking didn’t equate to a passion for running a woodworking business. An opportunity came to join Freud Diablo cutting tools as a product expert. I signed on, and over 15 years have passed. These days I’m their training director. I still keep a shop with a friend, but, honestly, I don’t get down there as often as I’d like. However, the thoughtfulness and care toward work that I learned through woodworking inform everything that I do.

I find inspiration from the creativity of other woodworkers, and I love how Fine Woodworking shares this. Have you seen Heidi Earnshaw’s white oak dresser? It is so clean and timeless. What about Israel Martin’s shop or his cabinet made from southern yellow pine? It blows my mind that such a common wood—the same species that my pressure-treated deck is made from—could be reinterpreted into such an elegant piece. Check out Sarah Watlington’s cabinet on a stand. The grain and balance are amazing. It’s incredible what people do, how they express themselves through form and function.

Kevin Kauffunger

|

A Love of the Craft, ExposedHeidi Earnshaw’s white oak seven-drawer dresser is based directly on the 18th-century French semainier form, which had one drawer for each day of the week Jonathan Binzen, Heidi Earnshaw |

|

Israel Martin’s Shaker-Style CabinetSimple wood, good proportions, and the use of the wood grain to enhance the design are the hallmarks of Israel’s Shaker-style cabinet. Fine Woodworking editors |

|

Shop Design: My workshop in northern SpainIsrael Martin renovated an 18th-century stone house in the Cantabria region of northern Spain for his all-hand-tool workshop. Israel Martin |

|

Sarah Watlington’s Cabinet-On-StandInspiration for this cabinet-on-stand came from many places, says this graduate of The Krenov School. Fine Woodworking editors |

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in