Contemporary Woodworking in Thailand

The country is rich and rising in fine furniture and woodcraft

Synopsis: Robert Sukrachand has been on a mission exploring Thailand’s craft and furniture design communities. Here he tells the stories of six leaders in the country’s woodworking renaissance. Their stories are as diverse as their furniture designs.

Having split time between the United States and Thailand as a kid, I’ve always looked out for ways the two places relate. When I found them, those moments made my two homes feel closer to one another. This was the sort of connection I was seeking in 2017 when, as a Brooklyn, N.Y.–based woodworker and furniture designer, I set out on a trip to Thailand to begin collaborating with the country’s resurging craft and furniture design communities.

In the years since, I’ve found exactly those moments of connection in my visits to the studios of Thailand’s new crop of woodworking furniture designers. The connections started in Bangkok, the country’s capital. Then, as I transitioned to living part-time in Thailand, my own work in the country as a designer led me farther afield to rural reaches and the country’s northern cultural capital, Chiang Mai.

Below are the diverse stories of six leaders in the country’s woodworking renaissance. Far from a monolith, this cohort of contemporary Thai makers parallels a broader Thai society constantly in flux—thoroughly modernized and in touch with the West on one hand, but also increasingly introspective as many young Thais look to rekindle a touch of the past and a traditional, slower way of life.

|

|

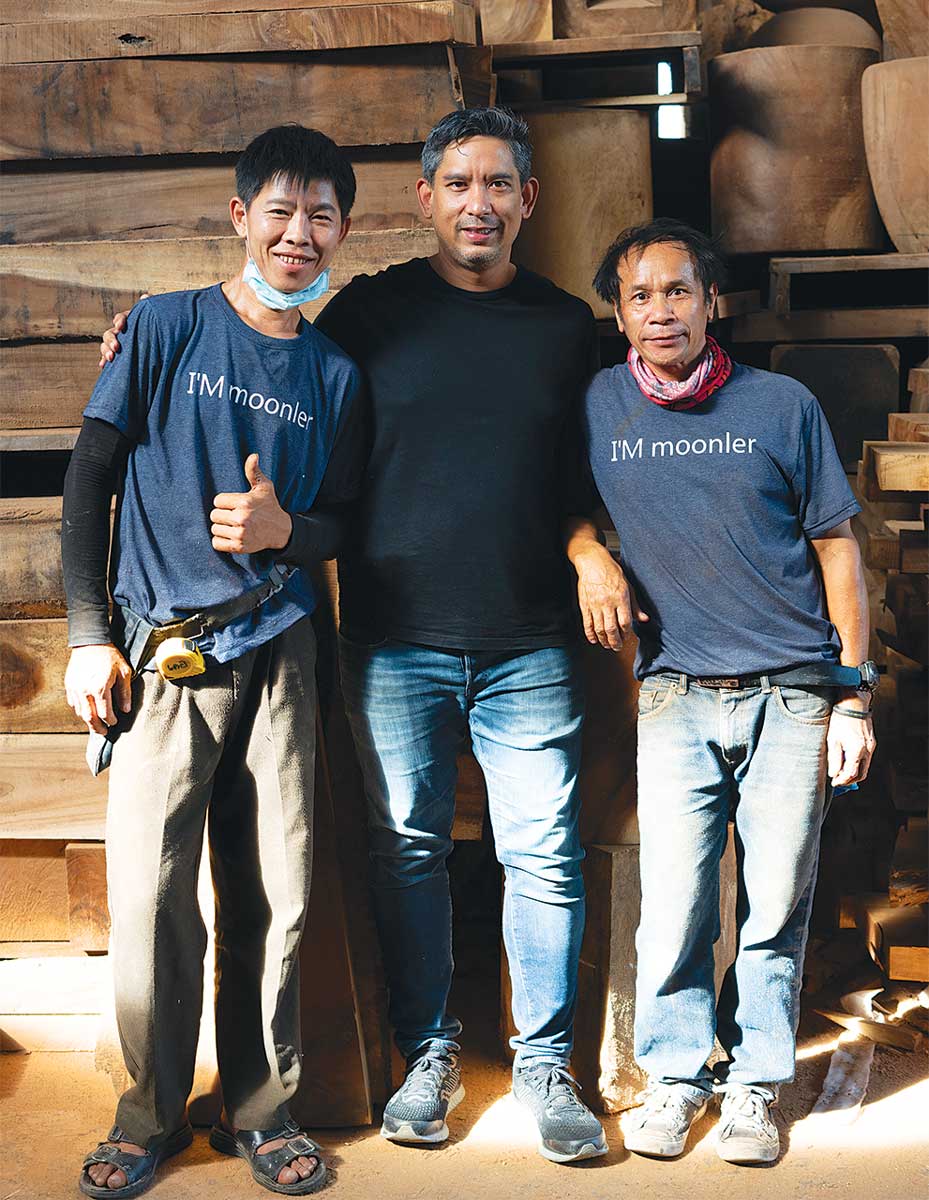

Moonler Collection Co.

About 15 kilometers outside of Chiang Mai’s city center, Moonler Collection’s sprawling workshop vibrates as the company’s 30-plus employees turn local charmchuri lumber into elegant tables and chairs. Having nicknamed themselves the Charmchuri Wood Whisperers, Moonler’s team of designers and craftsmen focus on elevating this overlooked species.

About 15 kilometers outside of Chiang Mai’s city center, Moonler Collection’s sprawling workshop vibrates as the company’s 30-plus employees turn local charmchuri lumber into elegant tables and chairs. Having nicknamed themselves the Charmchuri Wood Whisperers, Moonler’s team of designers and craftsmen focus on elevating this overlooked species.

Moonler’s owner, Phuwanat Damrongporn, moved to Chiang Mai in 2008 to collaborate with local craftspeople. Visiting the craft village of Baan Tawai, Phuwanat was disappointed in the quality of the furniture he found. Knowing that he could improve on it, he hired his first and longest-serving employee, Kur, and the two began building furniture—at first with minimal tools, as they couldn’t afford a full shop.

Phuwanat and Kur found an abundance of wood to work with. In the neighboring provinces of Lampang and Phrae, local entrepreneurs rely on the charmchuri tree to harvest the shellac excretions from the Kerria laca bug. The fast-growing trees eventually stop attracting the bug and are felled, creating ample supply of the lumber.

“At this time, Thai people only wanted to buy furniture built out of teak and rosewood. They were not interested in charmchuri furniture because the material was traditionally seen as cheap and only used for woodcarving,” explains Phuwanat, who saw an inherent beauty in the grain and flexibility in the size and color variation. Sensing opportunity overseas, the young brand exhibited its first collection at the Thailand International Furniture Fair in 2010, finding ample interest from buyers in Singapore and Japan. The furniture is now exported across Asia and North America, and most of Moonler’s new collections are designed by Thailand’s top independent design studios. The Moonler team still sticks to its roots, building everything in-house.

|

|

Nucharin Wangphongsawasd

Ever since she was an undergrad studying industrial design at the King Mongkut Institute of Technology, Nucharin Wangphongsawasd, who goes by Nuch, has had an interest in designing her own furniture. But, as she explains, “traditionally in Thailand we have carpenters who build houses, and then designers who work with fabricators. I wasn’t even familiar with the concept of a woodworker who both designed and built their own furniture.”

Ever since she was an undergrad studying industrial design at the King Mongkut Institute of Technology, Nucharin Wangphongsawasd, who goes by Nuch, has had an interest in designing her own furniture. But, as she explains, “traditionally in Thailand we have carpenters who build houses, and then designers who work with fabricators. I wasn’t even familiar with the concept of a woodworker who both designed and built their own furniture.”

Nuch, 37, began exploring this concept in earnest in 2009 after being accepted into the furniture design program at the Rochester Institute of Technology. “I had no clue what I was getting myself into,” Nuch explains. “I remember the first day when my mentor told me what tools we needed to buy for our projects, and I had never even heard of them before. I was scared at that time, but I knew all I could do was give it a try.” That openness and lack of rigidity seems to have contributed to Nuch’s signature style of free-flowing furniture and wood objects. Rarely static, her technically complex works sway through the thoughtful use of bent-laminated and kerf-bent components.

After returning to Bangkok and setting up her own workshop, Nuch was promptly awarded a Wingate Residency at the Center for Art in Wood, in Philadelphia. There in 2016 her woodworking vocabulary further shifted. “The older I’ve grown the more delicate my work has become.” That development can be seen in her recent series of delicately bent tabletop objects, which she hopes slow the viewer down in order to fully appreciate them. Now Nuch focuses mostly on teaching young people at local universities and deepening her exploration of her preferred bending techniques. “How far can you push it? That’s what excites me now.”

|

|

Charnon Nakornsang

In Charnon Nakornsang’s home studio on the outskirts of Bangkok, there is little separation between his work and home. His small woodshop is full of the warm and exquisite details many woodworkers save for their most refined pieces of furniture. Just steps away, entering the front door of his home, a visitor’s jaw is likely to drop at the grace of his furniture, the visual balance in which he displays his work, and the mesmerizing light.

In Charnon Nakornsang’s home studio on the outskirts of Bangkok, there is little separation between his work and home. His small woodshop is full of the warm and exquisite details many woodworkers save for their most refined pieces of furniture. Just steps away, entering the front door of his home, a visitor’s jaw is likely to drop at the grace of his furniture, the visual balance in which he displays his work, and the mesmerizing light.

Charnon, 34, came to woodworking after 10 years as a graphic designer in Bangkok. “Growing up, I didn’t get to see furniture with real wood, just built-ins and plastic and metal things,” Charnon says while explaining his move into woodworking as a career. While watching the film The Great Gatsby, he was enchanted by the walnut clock, wood details, and warm palette of Tobey Maguire’s cottage. “I started researching this idea of living with wood all around you, and that’s when I discovered Nakashima, Krenov, and Esherick.”

Charnon was taken with the workshops and hand tools of these artisans as much as with their furniture. After taking a class in using hand tools to build a chair, he was hooked. “It became a full-time hobby and I began to sell some pieces. After work and on the weekends, I would work on my furniture projects whenever I had time.”

|

|

Around the time of Thailand’s first COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, Charnon left graphic design behind and commited to furniture full time. He continues to make his home life and workshop blend seamlessly, building furniture for daily use, such as a step stool for his daughter who loves to help in the kitchen. Taking a moment to appreciate the fine joinery and details in Charnon’s work, mostly made out of American hardwoods like walnut and cherry, one is struck by the way that wood knowledge and aesthetics travel across the world. Indeed, atop one of his finely finished tables lies a copy of Krenov’s A Cabinetmakers Notebook, whose philosophy is as elemental to Charnon’s woodworking style as it is to any student in the Redwoods.

|

|

Nanu Youttanakorn

In 2012, after 10 years as a graphic designer in Bangkok that he describes as “draining,” Nanu Youttanakorn decided it was time for a change. He was accepted into the master’s of social design program at Design Academy Eindhoven, in the Netherlands. Knowing that his study would primarily be workshop based, Nanu wanted to freshen up his making skills. So he approached Phisanu Numsuriyothin, mentor to many Bangkok-based furniture makers. “Phisanu got me hooked on woodworking,” explains Nanu, 39.

In 2012, after 10 years as a graphic designer in Bangkok that he describes as “draining,” Nanu Youttanakorn decided it was time for a change. He was accepted into the master’s of social design program at Design Academy Eindhoven, in the Netherlands. Knowing that his study would primarily be workshop based, Nanu wanted to freshen up his making skills. So he approached Phisanu Numsuriyothin, mentor to many Bangkok-based furniture makers. “Phisanu got me hooked on woodworking,” explains Nanu, 39.

“Even though at Eindhoven we were doing workshops in all kinds of materials, whenever I returned to Thailand, it felt like I was always surrounded by wood.” His mother collects old doors and windows from across the Thai countryside, instilling in Nanu an appreciation for found and reclaimed materials. Determining how to work with these materials, preserving organic forms while leaving his own imprint, has been a core pursuit for Nanu. “I’m trying to find the balance between control and letting go,” he says. “I only want to insert my intention where I need to, for example for a wood joint. It’s the contrast between natural and manmade.” An example of this contrast is his recent commission for the British ambassador’s residence in Thailand, a pair of benches built from a charmchuri log that grew on the British embassy’s former grounds.

His work has a hint of history and nostalgia. “The old way of life in Thailand was tied to wood materials: tools, transportation, buffalo carts, barges,” Nanu says. “These pieces have been worn and contain layers of time and texture. For me, it’s all about adding more and more layers in my furniture designs.”

|

|

Phakphoom Wittayaworakan

‘The world was spinning, and other people were working. Meanwhile, I was doing this work,” says Phakphoom Wittayaworakan, 43, as he explains the name of his studio, Meanwhile Woodwork. His open-air woodshop, which evokes the feeling of entering a rural Thai rice barn, has become a place for “thinking about what’s going on between body and soul,” he says. “Woodwork gave me the time to explore the inside, and to have a peaceful moment.”

‘The world was spinning, and other people were working. Meanwhile, I was doing this work,” says Phakphoom Wittayaworakan, 43, as he explains the name of his studio, Meanwhile Woodwork. His open-air woodshop, which evokes the feeling of entering a rural Thai rice barn, has become a place for “thinking about what’s going on between body and soul,” he says. “Woodwork gave me the time to explore the inside, and to have a peaceful moment.”

Phakphoom, who goes by Pop, grew up in this same village in Buriram Province located about four hours northeast of Bangkok. After studying to be a veterinarian, Pop moved to the capital and opened a clinic. During the 2011 monsoon season, now referred to as the Big Flood, unusually intense rains made life unbearable for many Bangkokians and stirred Pop to return to his childhood home.

The land that now houses his workshop and fruit and vegetable orchards was then sprawling rice fields owned by his mother. Settling in, Pop built his studio from scratch, slept in the loft above, and began experimenting in making small pieces of furniture and wooden tabletop designs. Carving expressive bowls and trays soon became his focus. “Using hand tools was shaping me, or tuning me, to be more peaceful and calm. If I used a power tool, it had the opposite effect. The noise made me feel more aggressive,” Pop explains. The calm of his studio makes it a frequent pilgrimage point for many of his woodworking compatriots, including the momentous Found Wood workshop in 2015.

“As a kid, I never had a chance to work with tools, build things, or experiment with wood,” an experience many of today’s woodworkers can surely identify with. “I had a feeling that there was something lost,” Pop says, “and I had to go and find it.”

|

|

Thamarat Phokai

In 2000, Thamarat Phokai, then a first-year painting major at the Silapakorn University arts program, was walking home as he passed Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok’s famous Temple of the Emerald Buddha. Landscapers were felling tamarind trees, cutting the logs into small pieces, and discarding them. Instinctively, he grabbed as many sticks as he could hold, and brought them back to his studio.

In 2000, Thamarat Phokai, then a first-year painting major at the Silapakorn University arts program, was walking home as he passed Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok’s famous Temple of the Emerald Buddha. Landscapers were felling tamarind trees, cutting the logs into small pieces, and discarding them. Instinctively, he grabbed as many sticks as he could hold, and brought them back to his studio.

“I thought it would be fun to experiment with wood, because no one else in my program was using the material,” he says. Thamarat began carving small toys out of wood for fun. The next summer, while spending time with family in Sing Buri Province, he was taken by the kraat, a traditional Thai tool formed out of wood into an elongated arc used for steering buffalo through rice fields. Returning to his university, Thamarat began adapting this arc form into his own wooden sculptures.

After living in Bangkok for 14 years, Thamarat purchased a small plot of land in the mountainous northern region Chiang Dao. Building a small house and separate workshop, he began focusing on working with wood. Thamarat’s furniture and murals are built completely by hand with chisels and handsaws. The only electrified tool he owns is a rusty bandsaw, which rarely gets turned on.

“My inspiration comes from the natural materials around me that I live with everyday. Just like a stone in the riverbed here has texture, the pieces of wood that I work with have unusual character,” he says. Rather than removing that character, Thamarat preserves it. Averse to glue and sandpaper, he builds every one of his chairs to knock down into individual components. His work life blends seamlessly with the studio surroundings and mountain hamlet. “Even the leaves that I look at outside of my workshop every day provide inspiration,” Thamarat explains.

When he’s not building furniture, you might find Thamarat carving a massive wooden totem or, as he was on my visit, chiseling traditional finial components for the local temple.

|

|

Robert Sukrachand is a woodworker based in New York, N.Y.; and Chiang Mai, Thailand.

From Fine Woodworking #298

From Fine Woodworking #298

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

A wealth of woodworking talent

A wealth of woodworking talent

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in