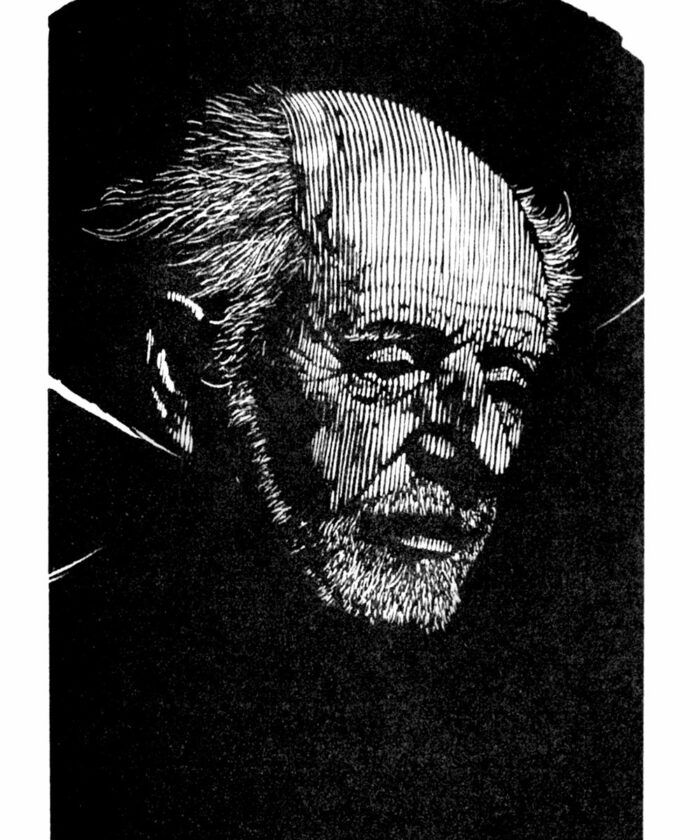

From the bench: Engraving Krenov

First the man taught him lessons about woodworking and life. Then, the process of creating an engraved image of James Krenov carried some lessons of its own.

Synopsis: First the man taught him lessons about woodworking and life. Then, the process of creating an engraved image of James Krenov carried some lessons of its own.

I discovered James Krenov’s books at the beginning of my woodworking journey. Both his writing and his furniture hit a nerve and they have affected me ever since.

For years, woodworking was an occasionally needed day job fueling my musical career. But in my early 30s I found myself at a fork in the road. What I was doing didn’t feel like a great recipe for a happy future, and I had begun to realize how much I liked making things and how little I really knew about it. This, and a host of other things, led me from Boston to California and the College of the Redwoods to actually study with James Krenov. Ten minutes at the school confirmed my decision: I was knocked out by the quality and creativity of the work I saw; I was humbled and eager to learn.

Two years later, I made my way back east and started the slow process of becoming a solo furniture maker/ designer. This was a tortuous path with many detours, wrong turns, and dead ends. Some of the side roads I traveled were more fun than profitable, but that never stopped me. (Luckily, playing music had taught me to live on a shoestring.) I made my own hardware, dipped my toe into fly rod building, metal engraving, toolmaking, boatbuilding…

At some point, under the spell of Wharton Esherick and his beautiful block prints, I decided to try making prints from wood engravings. Engraving wood, I found, was much like engraving a linoleum block—which many of us did as kids in school—except more interesting. You work with tiny sharp tools on the end grain of extremely hard, close-grained woods like boxwood and pear, which can hold a ridiculous amount of detail. Just the thing for an obsessive, fussy woodworker. The lines you cut print as white, which is to say they do not print at all: The ink stays on the uncut surface of the block and you work in reverse of drawing, starting with a black block and “erasing” what you don’t want inked. The work progresses slowly, and it can be disquieting, because as you work, you’re looking at the mirror opposite of what you intend to print.

The trip down this side road went pretty well, and I made a number of prints, even selling some (maybe because they had good frames?). Most of my prints were landscapes or details of local maritime scenes.

Then, in 2009, Jim Krenov died. I decided to engrave his likeness: a tribute to the man who had inspired so much in my life.

Sometimes you reach a point when you realize that if you don’t do something or other, you probably never will. Successfully drawing a human face was one of the hardest things I could think of trying to do. Drawing a recognizable, known one seemed even harder. I decided that this was the time, and so I set off down that path.

I’d had some pretty basic art training way back in grammar school. What stuck with me from it was the concept of drawing what you see, not what you think you see. This elemental truth of representational drawing has been helpful to me when sketching furniture, and I remembered that basic lesson as I set out to learn the details of Jim Krenov’s face, essentially to map it.

I would ultimately be working in black and white, so drawing in pencil was the right first step. That and finding every photo of him I could. I drew his face constantly, copying the lines, shapes, and wrinkles as closely as I could, eventually getting to know the terrain of his face. Drawing, I told myself, is just putting black marks on paper; the trick is to get them in the right places at the right size.

After making many drawings, I selected the best photo of Jim that I had (taken by David Welter while I was at the school), drew it to the best of my now enhanced-by-practice ability, and transferred it to a block of boxwood. As I began engraving, Jim gradually appeared in the block, my time studying the map of black and white which I now identified as his face slowly paying off.

Jim knew that most of his students were obsessive and capable of going too far, so “knowing when to stop” was a fairly frequent topic of his. The end point of a project is a moment of choice, and often arbitrary. I chose to stop engraving and have the block printed while leaving a deep crack in the surface.

That seemed apt. Jim, inspirational and far reaching in his influence, was also very human; he had his cracks and flaws. I learned an awful lot at that school and from Jim’s books. Hopefully this print put some of that to use.

John Cameron works and engraves wood in Gloucester, Mass. Prints of his engravings are available at johncameroncabinetmaker.com.

Photo courtesy of the author

|

From the bench: My mentor, Mr. Scriven |

|

From the bench: A splash of cold water |

|

From the bench: A bag of old chisels |

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in