Bottom feeding in the woodworking world, part 1

Within the scrap bins of commercial shops, a bounty of excellent wood can be found.

Before I delve into this month’s story about scrap pieces and design in wood, I want to share with you some wonderful news. My save-from-the-trash regency game table found a loving studio to go to.

As you recall, in December, I wrote about a falling-apart, yet still pretty unique, antique furniture piece that I found in the trash and was eager to give to a reader who would commit to restoring it. I received more than a handful of adoption proposals from serious woodworkers, and after sorting through them, I chose the person I believe has the best prospects of succeeding in this task. The lucky winner is a graduate of the North Bennet Street School in Boston, the country’s most prestigious institution for teaching the art of furniture making and conservation. The winner, Conrad Chanzit, told me that after graduating from the Cabinet & Furniture Making program, he decided to stay for a fifth semester and specialize in furniture conservation. Conrad also mentioned that all the senior instructors are eager to partake in this endeavor and that I will receive visual updates on the progress.

I look forward to seeing how this conservation project unfolds.

Scraps and the origin of my woodworking journey

It is a well-known secret that the firewood bins in commercial woodshops hold vast potential. These bins are packed with production-line leftovers that the companies find hard to reincorporate into future projects but which are perfect for beginners or woodworkers seeking a design challenge. From the dawn of my woodworking career, and even before it, when I had just begun tinkering with wood and tools, I found these scraps fascinating and invigorating. For a start, they were free and available to experiment with. But the second reason was that I have always been game for a design-within-constraints challenge.

Working under constraints

Working under constraints is one of the best ways to stimulate creativity.

Constructive parameters are good for us since they direct us to devise a plan to harness the full potential of the materials at hand; they force us to contend with a challenge that might not arise if we had carte blanche or total freedom vis-a-vis resources. Don’t get me wrong, I do see a lot of value in giving creative individuals the freedom to work with a bounty of material and a plethora of fabrication techniques, but I also see how an excess of possibilities can debilitate the beginner’s mind, throwing the brain into a whirlpool of endless options and away from a coherent course of action.

I think that a bounty of materials and tools, in the hands of the inexperienced maker, often leads to a result that is a cacophony of shapes, colors, and textures devoid of a coherent focal point, backbone, or composition.

By comparison, starting small with some scraps and a limited amount of tools is a great way to ascend into productive woodworking. Later on, and after gaining a healthy design vocabulary, we can venture out to explore a more extensive array of materials and techniques and tackle it with an informed eye and a confident hand. But here is another truth about design: No matter how competent the designer or how affluent the client, those who do this craft professionally always work under constraints of materials, production technique, time, and budget. So it makes sense to train ourselves from the start to work within limitations.

|

|

Foraging for scraps

To get access to these small goodies, you can cultivate a relationship with a big woodworking business. Calling a company that produces hardwood cabinetry and asking if they can spare you some scrap lumber is a good idea, but paying a visit or emailing might be a better way. Lumberyards are another place to start. Even if they don’t have any distinct sale area for scraps, they might be convinced to let you buy cutoffs or other secondary wood pieces that were rejected by their professional customers. To motivate you as you’re foraging for scraps, think about that recent nature video you watched and imagine yourself as a bird of prey that descended on a carcass to munch on the leftovers that the lion left behind after taking his share. Toughening your spirit before your rendezvous with the scrap bin will make things easier.

|

|

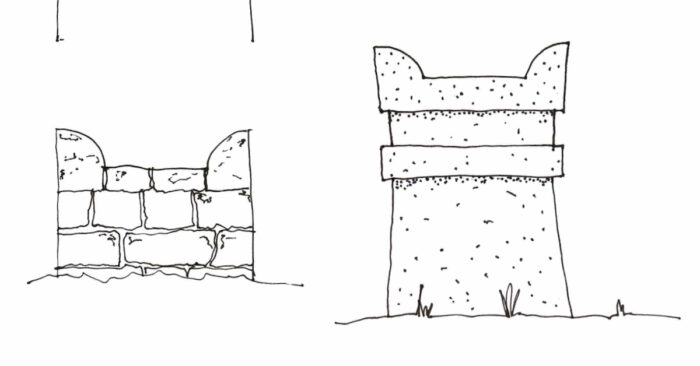

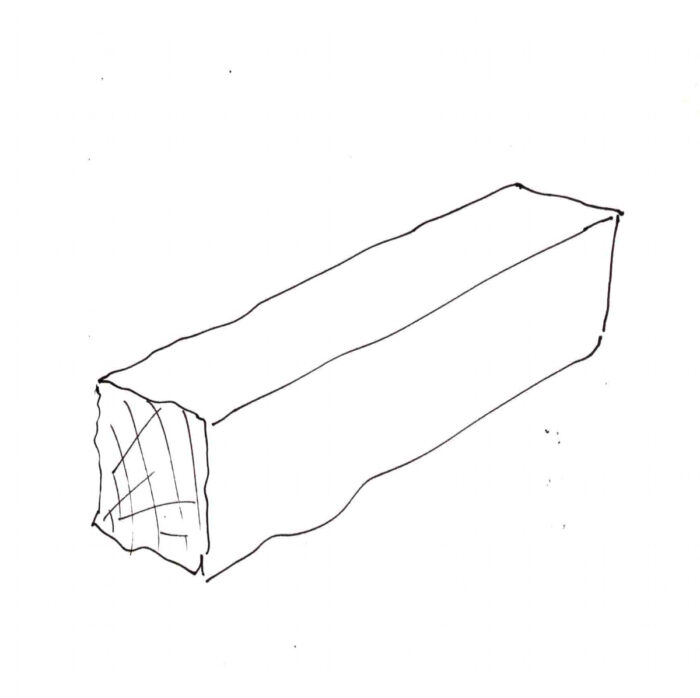

My One-Knife-Stand began as a scrap of maple. It was one of my first woodworking projects, built 25 years ago to fulfill my need to pedestal my first chef knife. The design mimicked the shape of the ancient Israelite/Canaanite Horned altar found in many archeological excavations. I tried to infuse the symbolic outline of a structure used for food offerings with a stand meant for a knife that chops vegetables. The symbolic horns also prevented the knife from sliding and falling from the “altar.”

|

|

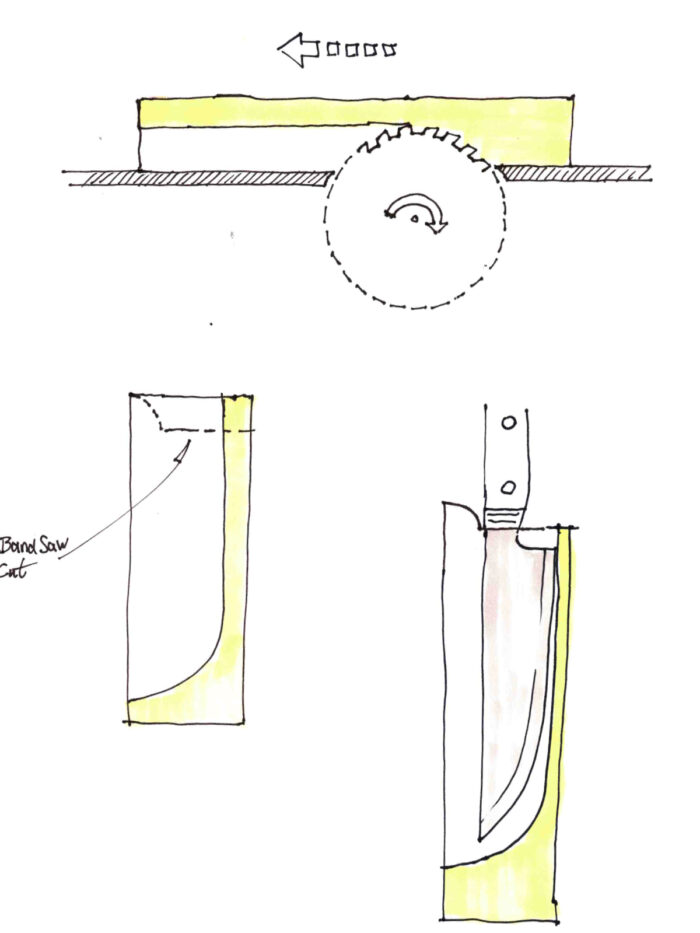

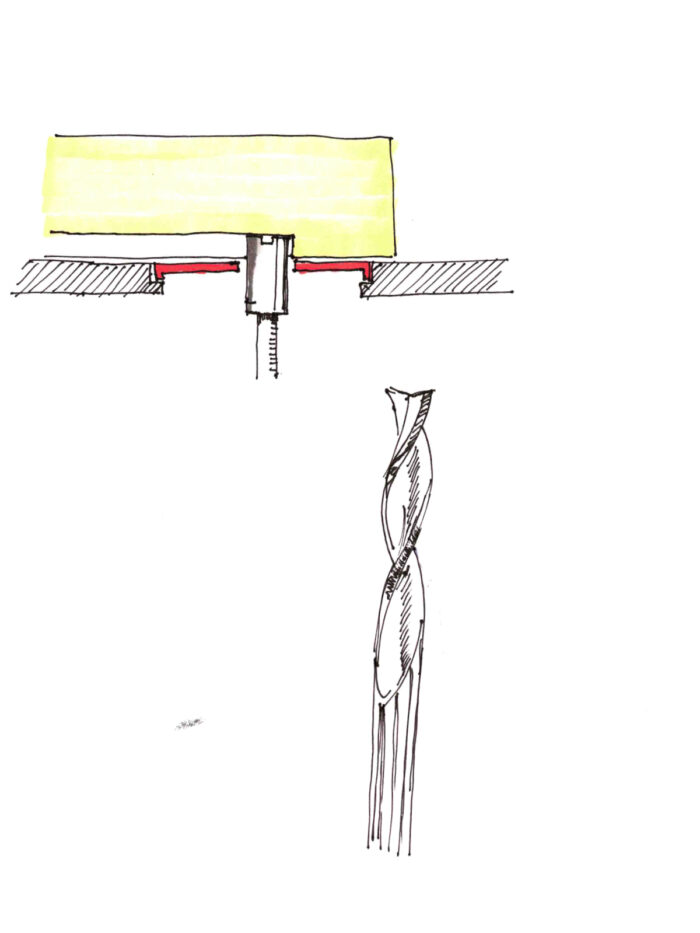

I used a table saw and a band saw to make a stand. I cut a stopped groove for the knife’s blade with the table saw, and I sculptured the horns with the band saw. Other ways to cut the knife’s groove are a router table and excavation with chisels.

My friend, master woodworker Thomas Newman, gave me these random sapele scraps. They were of the perfect topography to become a bluff of trees—a project I teach in the 6th grade. My students whittle the trees and then plant them in the sapele.

Tom’s studio uses sapele to fabricate some dreamy woodworking projects. The scraps he gave me were sawn off from components that were joined together to form futuristic chandeliers and furniture pieces.

|

|

|

|

Next time I will show and talk about some formidable scraps given to me recently by a top-notch design studio in Brooklyn, N.Y.

|

Dumpster diving into Fine Woodworking |

|

Fine furniture from reclaimed wood |

|

Wood hoarding |

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Sketchup Class

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Comments

Fun article! thank you.

Wow, what a timely article for me.

I am a designer (Industrial Design degree) and have been working wood for 40+ years. I recently discovered the absolute joy of letting my available "scrap" material influence my design solutions.

It started when I looked at my pile of practice hand cut dovetail joints and thought "what can I turn this scrap into?" I ended up making a "pencil" holder for my work bench.

My current project, still in work, was inspired by some 5/4"x6" square quarter sawn Cherry cutoffs that I had. I wanted to make a box but wanted it more like 6"x12" so I had to join some of the pieces. I decided to leave a 1/4" open reveal and used curly Maple splines to join them together for the sides.

Thanks for the inspirational article.

Hi Joel,

Your design approach is fantastic. I love the reveal and the wooden keys' stitches between the cherry tiles, and I think that the pencil holder is a joy to look at and make use of. Please keep me posted on the evolution of your scrap cherry box and any other scrap-related project down the road.

Cheers,

Yoav

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in