Desert woodworking

Traditional lessons on how to build wooden furniture in dry climates.

Originally titled “Desert Cabinetry” in Fine Woodworking #3—Summer 1976

The climate of the desert US Southwest can have a devastating effect on furniture. People moving there from the East often watch their antiques, which have survived hundreds of years in a relatively humid climate, break up before their eyes. Cabinetmakers suffer similar discouragement. It is rare to find even experienced cabinetmakers who have not had pieces ruined by cracks or broken joints.

The dangers of humidity, or lack thereof

As atmospheric conditions change, wood expands or contracts until an equilibrium moisture content is reached. Furniture from the East Coast has an equilibrium moisture content of twelve to fifteen percent. When this furniture is brought to the Southwest, its equilibrium moisture content may decrease to six percent with significant shrinkage resulting. Normal Midwestern hardwoods are kiln-dried to approximately twelve percent. When that lumber is shipped to the Southwest, the moisture content will decrease and cause shrinkage. Furthermore, seasonal humidity and temperature changes affect the moisture content of the wood and cause movement, which may result in shrinkage, expansion, distortion (such as cupping, warping, bowing, or springing), and even splitting.

Wood moves different amounts in different directions. Lengthwise movement is negligible. However, radial movement is significant, and circumferential (or tangential) movement is approximately fifty percent greater than radial movement. Therefore, joints between end grain and edge grain, and between plainsawn lumber (with tangential movement across its face) and quartersawn lumber (with radial movement across its face) will be subject to significant stress upon changes in wood moisture content. (The same is also true in the lamination of different types of wood with different movement characteristics.) This stress generates tremendous forces which can break joints and split wood.

A rich history

Many cabinetmaking techniques used to minimize wood movement can be seen in New Mexican Spanish Colonial furniture (hereafter, Spanish Colonial furniture). Modern Spanish Colonial furniture is the embodiment of a desert cabinetmaking tradition stretching back for centuries. The Arabs from Syria and Egypt and the Berbers from Northwestern Africa (collectively called the Moors) introduced designs and techniques from their homeland during their long occupation of Spain. By the beginning of the 17th century when colonists supplanted Conquistadores in New Mexico, the Spanish Moorish furniture design confluence had produced the popular mudejar style.

Although most colonists took little or no furniture with them, they did imitate the traditional and mudejar designs popular in Spain when they left. Their designs and execution were cruder than Spanish renditions and in native pine rather than the traditional Spanish hardwoods (mostly walnut). Nonetheless, they incorporated many of the cabinetmaking techniques used by the Spanish and Moors before them. The relative isolation of New Mexico and the fact that the original designs produced simple furniture that held up well under the rigors of frontier life enabled Spanish Colonial furniture design to endure for hundreds of years.

Even today, in small villages all over northern New Mexico, local craftsmen use the same furniture designs and techniques as their forefathers. In the larger towns and cities this same basic design and construction, often supplemented with Spanish and Mexican design and modern techniques, is used in commercial production.

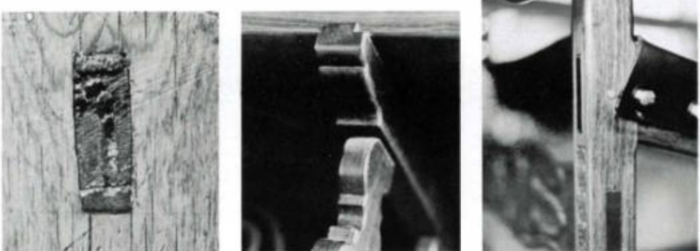

Doweled joints

One of the most conspicuous construction techniques in Spanish Colonial furniture is the doweled mortise-and-tenon joint. Of course, the mortise-and-tenon were not used merely to accommodate wood movement. Until the development of doweled joints, the mortise-and-tenon joint was the only one to use in many types of fine joinery. Nor would it be accurate to say that the doweling of the tenon is solely a desert cabinetmaking technique. It was used in fine furniture in many countries and was considered the best insurance against joint breakage from any cause. For whatever reason the doweled mortise-and-tenon joint was used in other countries, it does appear probable that its almost universal use in Spanish Colonial furniture and its continuation after virtual abandonment elsewhere is at least partly due to its ability to hold tight even when the glue joint is broken by shrinkage. The joining of edge grain to end grain is normally the point of greatest weakness and susceptibility to wood movement damage in furniture construction.

A characteristic feature of the Spanish Colonial doweled mortise-and-tenon is the almost exclusive use of only one dowel. European and American cabinetmakers often used two dowels at either side of the tenon to increase the strength of the joint. The absence of this extra dowel in most Spanish Colonial furniture is possibly due to the fact that shrinkage across the face of the tenon will cause stress to build up between the two dowels and split the tenoned piece. The use of only one dowel prevents such stress from developing.

Wedged tenons

Another characteristic of this joint, although seldom seen today, is the wedged tenon. Traditionally the wedges were driven in at the edge of the tenon. This compression of the pine tenon minimized loosening of the joint through shrinkage. To wedge the tenon with the crude tools they had, the New Mexicans broke with the almost universal Spanish tradition of using blind tenons and began cutting most mortises through. Modern makers of Spanish Colonial furniture have continued to use the through tenon for stylistic reasons even though the main reason for its use, ease of tenon wedging, has been largely abandoned tenon is the almost exclusive use of only one dowel. European and American cabinetmakers often used two dowels at either side of the tenon to increase the strength of the joint.

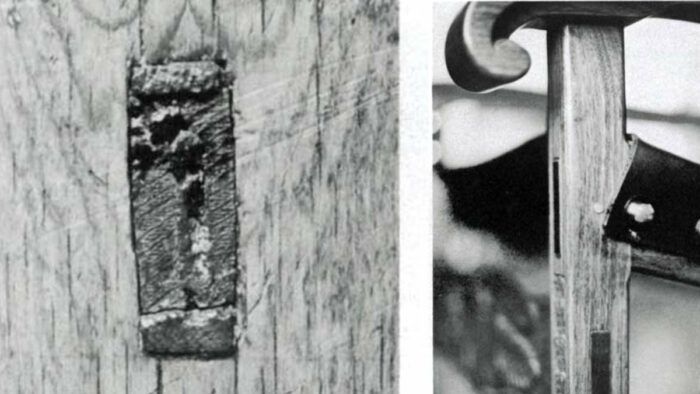

Removing tenons

The absence of offset tenon doweling is sometimes used in the Spanish Colonial doweled mortise-and-tenon joint. The dowel hole is bored through the mortised piece (with a waste piece inserted in the mortise to prevent breaking out of the mortise sides). The tenon is inserted, and the mortise dowel hole marked on it. The tenon is then removed, and the dowel hole bored, offset slightly toward the shoulder of the tenon. A tapered dowel is then cut 1/8-in. shorter than the dowel hole. When the dowel is inserted, glue is used only on the final 1/4-in. to prevent the dowel from protruding when the piece shrinks.

When driven home, the tapered dowel wedges the tenon shoulders tightly against the mortised piece, resulting in a joint that will stay extremely tight even if the tenon shrinks away from the mortise sides.

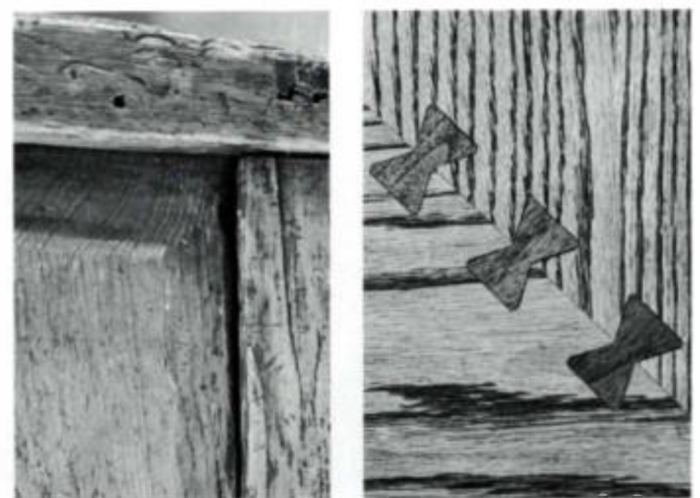

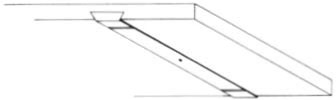

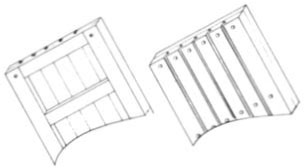

Dovetailed billets

Another movement-accommodating feature in Spanish Colonial furniture is the dovetailed billet. It was a unique Spanish method for attaching trestles to table tops. It was not widely used in colonial New Mexico, probably because the early New Mexicans could not execute it satisfactorily with their crude tools, but has become a standard technique in modern Spanish Colonial furniture. It is made by first cutting dovetail dadoes the width of the table top at the places on the bottom where the trestles attach. A tight-fitting dovetail billet is driven into each dado, cut off flush with the sides and often molded. The trestle is usually then attached to the billet by hinges, screws, or bolts. Thus the table top is free to float on the billet while the legs are still firmly attached.

This system not only prevents splitting but also controls the cupping tendency of plain sawed table tops. When the table top shrinks, the billet will invariably protrude. An improvement on the technique is to drive in a short billet, leaving approximately 1-½ in. of dado at each end. Then end plugs approximately 1-⅜-in. long are glued into each end, leaving shrinkage joints of 1/8 in. To prevent all movement from accumulating on one side, a dowel is inserted through the middle of the billet and into the table top.

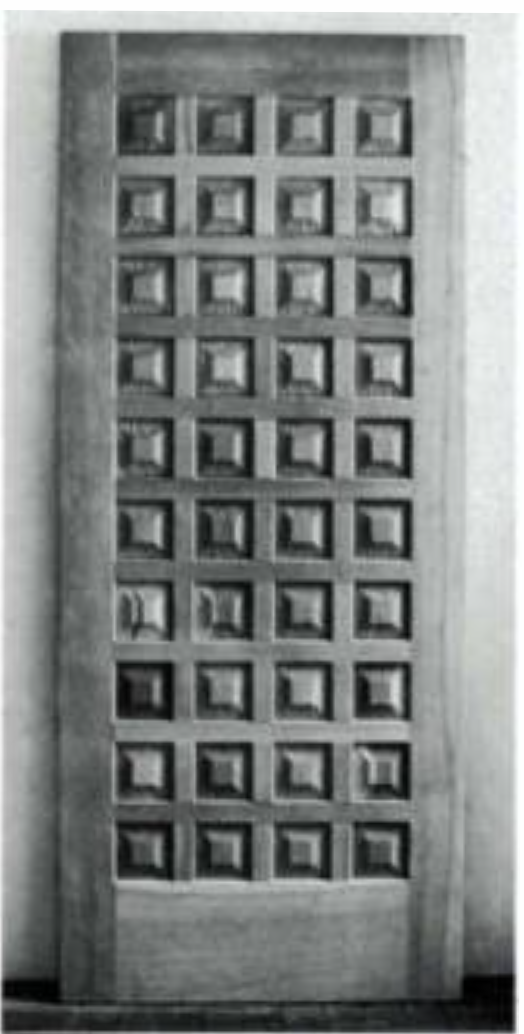

Multiple paneling

The next three movement-accommodating techniques can be traced directly to the Moorish influence in Spain. The first is multiple paneling. Also used on furniture, this technique is most common in large door construction. The rationale for multiple paneling is as follows: a wide panel will shrink considerably across its face, thus loosening the panel in the frame and exposing the unfinished panel tongue and even the panel edge. Multiple panels across the same width will each shrink less and cause less tongue exposure and loosening per panel. Moreover, the smaller confinement of the wood gives it less room to distort on the panel face. An additional feature of this frame-and-panel construction (and an essential feature on any frame-and-panel) is that the panels are never glued into the frame groove.

The sheathed door

Another Moorish technique is the sheathed door. It is made by sheathing a rigid door frame on one side with vertical boards. The boards are joined without glue by a shiplap or tongue and groove joint. Each board is then attached to the frame at the top and bottom by a nail, screw, or bolt. Thus, each board is held independently and can move freely without affecting the shape or appearance of the door.

Turned spindles

The technique of replacing solid panels with a series of turned or shaved spindles is also derived from Moorish woodworking. Shrinkage in the spindles is inconsequential compared to that in a panel, and ordinarily does not affect the appearance of the piece. This device can be seen in cupboards or trasteros, as well as in certain headboard designs.

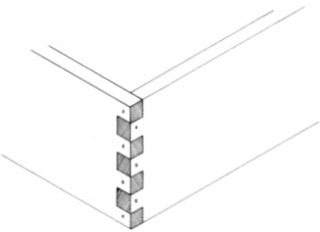

Doweled finger joints

The early New Mexicans sometimes substituted a doweled finger joint for the traditional through dovetail in their chests or arcos. Characteristically they used wide fingers and doweled through only one side. A superior joint was produced, however, in 15th-century Spain, where the fingers in each side were doweled. The resulting joint held even with broken glue lines, as long as the bottom or top remained in place.

Butterfly keys

The double dovetail or butterfly key across edge joints has come into fairly widespread use in modern Spanish Colonial furniture. Although many times only thin inlaid ornamentation, the key can significantly inhibit edge joint breakage due to shrinkage distortion when amply made and carefully inlaid.

Handling edge joints

Careful edge joint preparation by the Spanish Colonial furniture maker reduces the possibility of joint breakage caused by shrinkage distortion. (Edge joint gluing is a relatively recent phenomenon in New Mexico and Spain. Early cabinetmakers had single pieces of almost any needed width or thickness, or used an unglued tongue-and-groove joint.)

Often a gap in an edge joint must be planed true before gluing even though it can be pulled up with clamps. Further shrinkage may increase the spring and break the joint. Sawed edges are jointed before gluing unless extremely smooth and straight. If possible, prepared edges are glued relatively quickly before further wood movement distorts the edge line. The glue joint is allowed to dry thoroughly before surface planing or sanding. This is to prevent a depression from forming at the glue line when the wood, which swells with the moisture of the glue, shrinks back to its original position. If several plainsawn boards are glued up, the annual ring arc in the end grain is reversed alternately, so that cupping of the individual boards does not cup the entire piece.

Choose your wood carefully

Wood selection is another important aspect of the Spanish Colonial furniture maker’s wood movement awareness. An extremely popular wood is the very stable Honduras mahogany. Relatively stable black walnut and white pine are also used extensively. The most movement-conscious cabinetmakers try to use relatively straight-grained material. They also try to use quartersawn lumber in preference to the more beautiful but less stable plainsawn material. (Unfortunately, quartersawn lumber is now practically unavailable.) Also , when laminating, the Spanish Colonial cabinetmaker tries to choose material of similar movement characteristics, matching wood types and avoiding a combination of plainsawn and quartersawn stock.

Use drying methods to your advantage

When possible the Spanish Colonial furniture maker chooses lumber that has had time to air-dry to the ambient equilibrium moisture content over lumber recently shipped from the kiln. (The rise of solar-heated kilns may soon allow lumber yards in the Southwest to dry furniture wood down to acceptable moisture levels, thus allowing production shops to use properly dried material.)

Some Spanish Colonial makers use relatively ‘wet’ wood to their advantage by making [mortised] pieces out of it before it dries and making [tenoned] pieces out of drier wood. After gluing, the [mortised] piece shrinks to hold the joint more tightly.

Glue-ups and finishing

Many Spanish Colonial cabinetmakers now use synthetic glues, most notably aliphatic resin. However, some continue to use liquid hide glue extensively. The low moisture resistance of the glue is less of a problem in the desert, and its tough elasticity allows it to stand a fair amount of joint movement before breaking.

Movement accommodation considerations have played little part in the choice of finishes. In colonial New Mexico little or no finish was used on furniture. Today relatively low moisture-resistant oil finishes are the most popular. One of the reasons for this could be that the finish on furniture does little to retard seasonal or longer moisture content changes, and shorter changes affect the wood moisture content insignificantly. One rule of furniture finishing almost universally followed by the Spanish Colonial cabinetmaker is to finish both sides of any board liable to cup, and to use a finish with similar moisture-resistant qualities on both sides. A final traditional rule of the Spanish Colonial cabinetmaker is to avoid endbanding of solid stock if at all possible. Not only does it lead to an unsightly overhang of the end band, but it will break the banded plank if secured tightly at more than one point.

Not just for westerners

The Spanish Colonial cabinetmaker is in many ways the present embodiment of a long and fascinating tradition of furniture making. However, the movement-accommodating techniques that have developed as part of that tradition should not be of interest solely to the desert cabinetmaker. Wood moves with the temperature and humidity of the air around it. In a New York City apartment which is heated in the winter and open in the summer, wood moisture content may change more than in the desert. Few cabinet makers know whether the lumber they use is at its equilibrium moisture content, or whether the furniture they build will be moved to a markedly different climate. For these reasons every cabinetmaker, no matter what style of furniture he or she produces, must make design and execution decisions with the possibility of wood movement in mind. The history of Spanish Colonial furniture construction can offer valuable techniques useful in minimizing the effects of that movement.

|

Keep it comfortable for you and your tools |

|

Building a humidor |

|

How to understand wood movement |

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Jorgensen 6 inch Bar Clamp Set, 4 Pack

Bessey K-Body Parallel-Jaw Clamp

Comments

"The climate of the desert US Southwest can have a devastating effect on furniture. People moving there from the East often watch their antiques, which have survived hundreds of years in a relatively humid climate, break up before their eyes."

I'm curious about the inverse/opposite situation...? I live and build fine furniture in the dry mountain West. If furniture pieces move to a more humid climate like the East Coast, and wood movement is planned for accordingly in the building process, are the results still as catastrophic? I would think it would be more advantageous to go from a dry climate to a more humid climate than the opposite..? Anyone out there have any comments or experience with this??

I moved back to southern New Mexico several years ago bringing with me about 3 1/2 tons of rough cut wood I had harvested in Virginia. I have black walnut, hickory, white and red oak, cherry and Osage orange. My sticker Ed stacks continue to air dry with the wood well below 8 percent. Humidity here is usually 10-18 percent. So far the pieces I built inVirginia are holding up well. I like figured wood and have placed keys to stop some cracks from expanding. One stool, white oak bottom and dogwood top that I made in Virginia went to Colorado, New Mexico and back to Vieginia. So far no noticeable issues. I used split tenons on the one. My belief is once wood gets down to a very low moisture level the expansion in a more humid area is minimal. Items left out in the southwestern sun however, die a slow death as everything shrinks in the sun and bleaches out. I built a be ch using an oak slab and wild vine for the backrests. The vine is doing fine but the oak is looking very rustic now. Hope this helps.

Thanks for the input, I appreciate it!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in