Mistakes are stories

Whether the goof-up happened today or back in Colonial times, the real story lies in how the woodworker recovered from it.

There’s a sentiment most woodworkers take to heart—for some, it’s good advice to follow whenever possible while for others it’s an unbreakable rule. Then there are those who seem to ignore the idea altogether.We woodworkers are quick to point out our mistakes to whomever is looking at our most recent project. It’s a defense mechanism, of course, a quick self-deprecation aimed to beat everybody else to the punch. These are generally little things that would never be mentioned if we didn’t have an outsized concept of perfection, but there are other kinds of mistakes that we do talk about, the kind that require effort and cunning to overcome, the ones that become our war stories. In addition to accumulating a few of these stories for myself over the years, I have also read quite a few in the tool marks and irregularities left behind on antique furniture. Mistakes are stories, or at least the McGuffins that drive our woodworking stories forward. Here’s one of mine and one from the 18th century.

Anticipating disaster

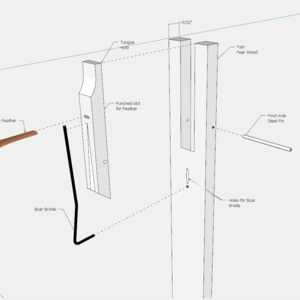

I’ve been building a complex library table with writing drawer copied from an antique in the Colonial Williamsburg collection (see the original here). While open, the writing drawer is supported by legs of its own, so its traditional dovetailed drawer box also needs some tenons on its front to fit into mortises in the legs. As I was knocking everything apart following my final dry-fit before glue-up, this thought came to mind: “This whole assembly is precariously perched on my bench, so I better reposition it … after this next mallet blow.” As you can guess, that next mallet blow sent the whole thing to the floor where it landed right on one of its tenons, ripping it in half, but miraculously causing no other major damage.

I typically work in front of the public, so I swallowed the four-letter words on the tip of my tongue and pretended to be cool about the situation. A broken tenon can be replaced by creating a slip tenon, so that’s what I did. I sawed along the vertical pencil line in the photo, removed all the ragged edges, and carefully drilled and chiseled a mortise in the end grain where the new tenon needed to go. By making this pocket an inch and a quarter below the baseline of the dovetail socket, I gave myself plenty of glue surface to create a joint that should be just as strong as the original. Hand cutting an end-grain mortise is not pleasant, but by putting in a little extra work, I saved myself from more work and wasted materials. I also gained a story to share with others who find themselves in a similar position.

Stories from the past

Enough of that – it’s easier to tell other people’s mistake stories, even when we don’t know all the details. This is a mahogany bureau table (also at Colonial Williamsburg) made by the mid-18th century Williamsburg shop of Peter Scott.

Scott made several of these unadorned, yet fashionable pieces, including a pair for Martha Custis who brought them into her marriage to George Washington. As is typical of fine period work, the interior surfaces reveal a coarse efficiency of workmanship that stands in stark contrast to the refined exterior. The picture below also reveals something else: a series of dadoes cut into the case sides that were then filled back in (it’s this way on both sides).

Are we looking at somebody’s layout error preserved in mahogany for all time? Probably, but the real story is the recovery, not the mistake. Scott’s workers knew that nobody would see the interior, so they could fill the dadoes and move on. It’s a good move especially considering that the through-dadoes (much faster to hand cut than stopped ones) were capped by a thin strip applied to the front edge of the case (it’s been replaced on the antique).

Did the same craftsperson who made the mistake also fix it? We’ll never know, but we do know that Scott did not work alone. In a 1755 newspaper ad announcing his planned return to Great Britain (he never left), Scott advertised two enslaved men for sale who were “bred to the business of a cabinetmaker.” Crass as the wording is, it tells us that these skilled Black cabinetmakers were likely part of this bureau table’s story too. Beyond that, only questions remain. Were they behind the mistake, the fix, or both? What, besides lost time, were the consequences of the mistake? That’s a hard question to ponder.

Mistakes left behind point to stories about people, not just furniture. We, as fellow woodworkers, recognize ourselves in the tragedies and triumphs of mistakes and their corrections. Some of these stories become the ones we love to tell, while others are the ones we’ve been running from for far too long.

More from Bill Pavlak

|

A very good cabinetmakerWiltshire worked in the cabinet shop owned by Anthony Hay, and like the building he worked in, the “very good cabinetmaker” was Hay’s property. |

|

Waste knot, want knotThere’s a sentiment most woodworkers take to heart—for some, it’s good advice to follow whenever possible while for others it’s an unbreakable rule. Then there are those who seem to ignore the idea altogether. |

|

Survival of the prettiestSometimes the worst thing you can do while copying an antique is to actually copy the antique. |

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in