A Maker’s Mark Leaves a Deep Impression

Throughout Aaron Keim's shop, many tools are marked with "KLS," reminding him of his friend.

In the past, it was common for hand tools to be stamped with the owner’s name or initials to deter theft and facilitate recovery if lost. A woodworker might have commissioned such a stamp from a blacksmith during their apprenticeship, a significant expense for a young maker. In my workshop, I pick up tools bearing various names—L. Sauls, C. Jenkins-Jones, and J. Lyons—on a daily basis. However, the majority of the marked tools belonged to “KLS,” Kenneth Lee Schultz.

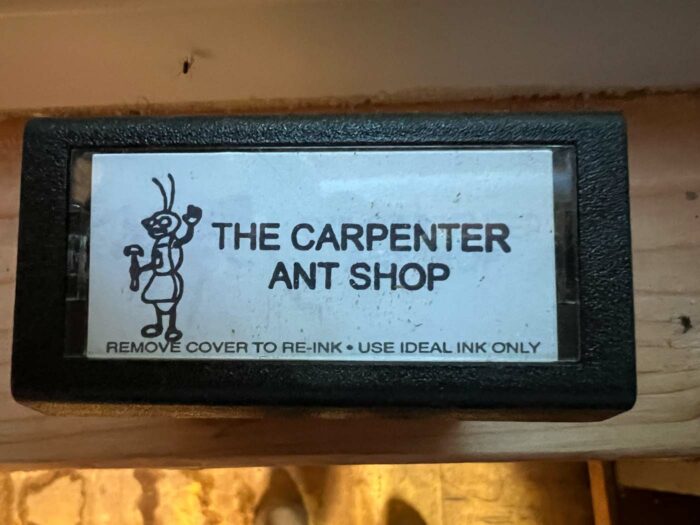

Ken was the father of Lizann, a friend, student, and patron of mine. We first met around 2008 at the Portland Ukulele Festival, and she began commissioning musical instruments from my shop around 2012. In 2018, Lizann asked for help clearing out her father’s workshop and garage, offering wood and tools in exchange. Ken, born in 1934, was a cabinetmaker and millwright who had a home workshop and a significant collection of wood. He would bring home his favorite boards, marking them with a “K,” as well as cutoffs and scraps from various projects. He inherited fine timbers from his father-in-law, who crafted grandfather clocks, including several from Hawaiian koa. In the 1970s, Ken milled a dogwood tree from his front yard, which I have since used in numerous projects. He named his home workshop “The Carpenter Ant Shop,” and I have accordingly dubbed the wood I use from his collection “The Carpenter Ant Stash.”

Ken was the father of Lizann, a friend, student, and patron of mine. We first met around 2008 at the Portland Ukulele Festival, and she began commissioning musical instruments from my shop around 2012. In 2018, Lizann asked for help clearing out her father’s workshop and garage, offering wood and tools in exchange. Ken, born in 1934, was a cabinetmaker and millwright who had a home workshop and a significant collection of wood. He would bring home his favorite boards, marking them with a “K,” as well as cutoffs and scraps from various projects. He inherited fine timbers from his father-in-law, who crafted grandfather clocks, including several from Hawaiian koa. In the 1970s, Ken milled a dogwood tree from his front yard, which I have since used in numerous projects. He named his home workshop “The Carpenter Ant Shop,” and I have accordingly dubbed the wood I use from his collection “The Carpenter Ant Stash.”

Ken was a dedicated lifelong collector, a term that politely suggests he was an organized hoarder. In addition to hand tools, machinery, fasteners, and lumber, he kept boxes of used sandpaper, coffee cans filled with twist ties, jars of unsorted hardware, shelves of burned-out motors, and hundreds of rubber bands made from old bicycle tubes. Since 2018, I have visited three to four times a year to assist with the ongoing task. The family’s beautiful turn-of-the-century Craftsman house near Portland, Ore., features a garage and a basement completely filled. We often approached the work with a specific goal, such as retrieving the table saw for my friend, rescuing all the koa wood for ukuleles, or hauling the cast-iron Delta planer up the stairs.

As we dismantled equipment for removal, we marveled at how Ken had managed to get it all into the workshop. He owned two bandsaws, a table saw, a planer, a jointer, a shaper, a lathe, a router table, a dust collector, multiple sanders and grinders, a drill press, an air compressor, and all the usual toolboxes and workbenches. As I became more familiar with Ken through my visits, I realized that his secret was patient and careful hard work. Even at 85, he helped load my truck, carrying impressive loads of lumber and proudly recounting how many sheets of plywood he used to lift at once. As dementia set in, he often repeated these stories, and I made it a point to reintroduce myself and explain my purpose at every visit. This seemed to set him at ease, and he enjoyed seeing pictures of the musical instruments I built from his wood.

Among the hand tools with “KLS” burned into them, I also have Ken’s notes to himself, written in permanent marker on various machines. Many of these notes appear to have been made as his body and mind began to fail him, serving as reminders of the planer’s feed direction, the router bit’s rotation, or how to tighten the bandsaw blade. He also labeled each board of lumber, though he seemed to grow confused near the end, misidentifying koa as teak or poplar as cedar. By examining his scraps, templates, and jigs, I glimpsed his thought process and work methods. I even discovered his sketches and story sticks, carefully saved alongside the scrap wood.

As Ken’s eyesight deteriorated, he often sat upstairs with his dog Hugo while we worked below. Twice, we enlisted groups of Lizann’s friends and family to help, removing paint and chemicals, sharing wood with other makers, and finding homes for the machines. As we made progress, Lizann was better able to make repairs on the home, some of which I helped with. My wife and son frequently accompanied me, and we all enjoyed the time spent visiting and talking as much as sorting and carrying. When Ken moved to assisted living, the burden of his care was lifted from Lizann’s shoulders, a relief for us. Ken passed away on August 23, 2024, with Lizann and her brother by his side. We will be singing at his funeral in a few weeks. Despite our efforts over the past seven years, the cleanup is not yet complete, but we will continue when the time is right. Ken’s abundance and Lizann’s generosity will take me a lifetime to repay. If you visit my shop, you will not leave without a handful of pencils from Ken’s stash.

As Ken’s eyesight deteriorated, he often sat upstairs with his dog Hugo while we worked below. Twice, we enlisted groups of Lizann’s friends and family to help, removing paint and chemicals, sharing wood with other makers, and finding homes for the machines. As we made progress, Lizann was better able to make repairs on the home, some of which I helped with. My wife and son frequently accompanied me, and we all enjoyed the time spent visiting and talking as much as sorting and carrying. When Ken moved to assisted living, the burden of his care was lifted from Lizann’s shoulders, a relief for us. Ken passed away on August 23, 2024, with Lizann and her brother by his side. We will be singing at his funeral in a few weeks. Despite our efforts over the past seven years, the cleanup is not yet complete, but we will continue when the time is right. Ken’s abundance and Lizann’s generosity will take me a lifetime to repay. If you visit my shop, you will not leave without a handful of pencils from Ken’s stash.

Aaron Keim is a woodworker, writer, and musician living in Hood River, Ore. He builds ukuleles, banjos, and guitars as Beansprout Musical Instruments (www.thebeansprout.com). He was the recipient of a 2022 research grant from Mortise & Tenon magazine, which he used to study the musical instruments made in Hawaii in the 1890s. He also enjoys carving, basket weaving, hiking, and learning the steel guitar.

Comments

Great article!!!

I was particularly hit with the name "The Carpenter Ant Shop". I just finished building a small box that I named "The Insect Box". I built it out of some left over wood elements in my shop including 6 small dovetailed right angle pieces that I used for "legs".... 6 legs=insect to me. I then added 2 "eyes" and some other elements to enhance the look just for fun.

I have a good friend who lives in Portland and has a few custom made banjos. I emailed him to see if he's familiar with The Beansprout. I'll report back when I hear from him.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in