Throwback: 18th-Century Workbench

In this article from issue #65, Scott Landis explores a long-respected workbench and its attributes.

Accustomed as we are to today’s benches, with their complex vises and involved construction, it’s easy to forget they didn’t start out that way. Like the automobile, the modern-day workbench evolved from a much simpler design. Yet unlike many other mechanical objects, one can make a case that much of the bench’s evolution since the mid-18th century has been icing on the cake—perhaps even superfluous.

In his classic four-volume treatise on woodworking, L ‘Art du Menuisier (Paris, 1769-1775), joiner/historian Jacques-Andre Roubo wrote, “The bench is the first and most necessary of the woodworker’s tools.” The bench Roubo describes is so simple it’s tempting to dwell on what it lacks. There’s no tail vise, no regimental line of benchdogs marching across the top, no quick action front vise, no sled-foot trestle base. A massive single-plank top supported by four stout legs, Roubo’s bench is equipped only with a large bench stop, a wooden hook screwed to the left front edge of the bench and an optional leg vise.

How, you may wonder, could such a primitive contraption serve for work on the refined furniture of Roubo’s day? How would delicate moldings be held or drawers be dovetailed ? The answer lies in the division of woodworking trades at the time, as depicted in Roubo’s engravings. The workers shown are architectural joiners, not furniture makers or cabinetmakers. Leaning against the wall of the shop are the fruits of their labor: windows, paneling, stair stringers, and the like. These men would have spent their time efficiently performing a few operations. The ability to trap short or irregular bits of wood in a vise, while critical for a cabinetmaker, would have been superfluous for the joiner. In looking at Roubo’s bench, it becomes clear that the type of work being done was a major determinant of the bench’s design.

Discovering Roubo’s workbench was, for me, a rare treat—akin to unearthing in some long-lost voyageur’s journal a description of my favorite canoe route. Finding a reproduction of the bench was even better. Its owner and builder, timber-framer and erstwhile medieval scholar Rob Tarule, enjoys the bench at least as much for what it tells him about the 18th century as for what it enables him to do. Perhaps most of all, Tarule enjoys the bench’s simplicity, observing, “That’s one of the things I like about it: four legs, four rails, twelve joints. It couldn’t be any simpler.”

The Roubo bench is so simple, in fact, that I couldn’t help wondering if Tarule was making a virtue of necessity. After all, the workholding system is the guts of a workbench. Wouldn’t woodworkers of the period have been the first to adopt more secure methods of holding the work if any had been available?

In answer, Tarule refers to Roubo’s plates—for the type of work shown, vises may not have been as efficient as simple stops and holdfasts. Roubo’s holdfasts are one-piece iron bars, hand forged in the shape of an L. The long leg, or shank, of the L is inserted in a hole bored through the benchtop. The bent corner, or head, is struck with a mallet or hammer, securing the work beneath the pad at the end of the neck. In the process, the shank is wedged firmly across the hole in the bench. The time spent engaging and disengaging the screw of a vise would have slowed down a joiner. One or two blows on the head of a good holdfast, on the other hand, will hold a board securely in almost any position; one quick shot on the side of the shank frees the work just as quickly.

Having decided to build a reproduction of the Roubo bench, Tarule first began searching for a top, described by Roubo as a single plank of hardwood, 5 to 6 in. thick, 20 to 24 in. wide, and between 6 and 12 fc long. “When I copy something,” Tarule notes, “I try to copy it as accurately as possible.” By the time he was through, however, Tarule had departed from the original Roubo bench several times in building his interpretation.

In the first place, nobody stocks dry wood that large, so Tarule knew he’d have to compromise on the top’s dimensions. (Roubo mentions that the benchtop tends to cup until it’s fully seasoned, suggesting the use of at least partially green wood.) After almost a year of picking over lumber piles at local Vermont sawmills, Tarule found a mammoth maple plank, which he was able to dress down to almost 5 in. thick, 18 in. wide, and 98 in. long.

After handplaning the top flat, Tarule set it aside and turned his attention to other projects. Two years passed, and Tarule took a job as curator of Mechanick Arts at Plimouth Plantation, a restored 1627 Pilgrim village in Plymouth, Mass. In need of a bench, he decided to resurrect the Roubo project.

With a few minor exceptions, all joinery and surface preparation was done by hand—to leave the appropriate tool marks. Tarule flattened the underside only in the area of the joints. Legs were cut from scraps of 4×6 red-oak floor joist material. Although the top was still relatively green, Tarule reasoned that this would allow the top to shrink and seat itself more tightly around the double tenon at the top of each leg. Roubo doesn’t mention glue, so Tarule assumed that none was used. Besides, joints that aren’t glued can be disassembled—no small blessing for Tarule, who’s had to move his bench several times over the years.

In the same spirit, Tarule decided not to reinforce the double tenons with wedges, as Roubo recommended. He planned to add them later if the legs loosened up, but he wanted to be able to remove the legs to transport the bench. In the process, Tarule discovered that by orienting the heartwood in the top up (as instructed by Roubo), the massive plank seated itself more firmly on the legs as it dried and cupped slightly.

Tarule made stretchers for the bench’s base of maple and cut a full-width tenon on each end. The tenon layout was not specified by Roubo, presumably because such construction details were understood by craftsmen of the period. The leg-to-stretcher mortise and tenons are pinned with two dry white-oak pegs driven into the marginally wetter red-oak legs, so the legs shrink tight around the pins as the drier pins expand slightly.

For strength, it was critical that the tenon shoulders fit tight to the mortised leg. Shrinkage across the width of the leg would open a gap at the shoulders, so less wood between pin and shoulder should mean less potential shrinkage and a tighter joint. But if the pin were placed too close to the shoulder, Tarule ran the risk of weakening the mortise. Thus, he placed the pins about 5/8 in. from the edge of the leg (they can be safely placed as close as 1/2 in.). He then strengthened the joint with drawboring, an old technique whereby the corresponding holes in the tenons are offset by about 3/32 in. toward the shoulder. Driving a slightly tapered pin through the holes in the assembled joint pulls the shoulders tight to the leg.

To store tools, Tarule filled the base of the bench with short lengths of l-in.-thick pine boards, resting on a ledger nailed to the inside of the long stretchers. The boards are positioned to allow the ends of planes to rest on the stretcher while keeping their blades just off the shelf.

Today, Tarule’s completed workbench is a testament to strength and simplicity. Because of the top’s shrinkage and the stable construction of the base frame, Tarule guessed that gaps would form at the bottoms of the short stretcher tenons where they entered the legs. Sure enough, they’ve all opened up a little, giving the bench a slight A-frame-like structure. Tarule speculates that this angularity might contribute to the bench’s overall rigidity.

After being resurfaced several times, the top measures 4-1/2 in. thick, 17-1/4 in. wide, and 98 in. long. It’s been given a protective coat of all-purpose “miracle finish”—a mixture of turpentine, beeswax, and boiled linseed oil used at Plimouth. This homespun recipe calls for about 2 oz. of melted beeswax (roughly an egg-size chunk) cut with a pint of turpentine.

The linseed oil is added in equal measure to the combined beeswax and turpentine. The bench is 34-1/2 in. high, several inches taller than Roubo’s specified 31-3/4 in. Tarule points out that recommended bench heights vary considerably among historians and practitioners. He agrees that a low bench allows for greater pressure in handplaning, but still finds a relatively high bench more comfortable. (Tarule is 5 ft. 8 in. tall, so the benchtop falls a bit below his elbows.)

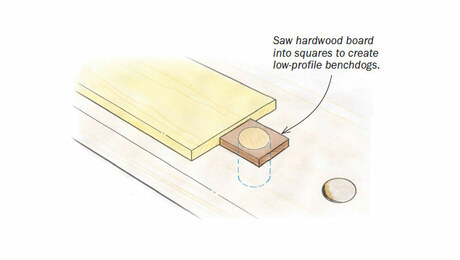

The stop and holdfasts transform this heavy table into a workbench. The 12-in.-long stop is made from a single chunk of white oak. It fits snugly in a square hole in the benchtop and is adjusted by tapping it with a mallet.

In the block’s top, Tarule installed a serrated iron hook (a flea market find) similar to the one drawn by Roubo. Although Roubo specifies the hook’s position in the block, Tarule has experimented with different placements. If the hook protrudes beyond the front edge of the block as described by Roubo, the block cannot be hammered below the benchtop for an unobstructed work surface. And due to the size of the hook’s square tang, it’s easy to split out the front of the block if the hook is installed too close to that edge. Tarule’s hook head is thicker than the one illustrated by Roubo, so he’s found it convenient to install it in the middle of the block, allowing the head to protrude about 3/8 in. above the block. In this position, the iron hook can’t be engaged if the top of the stop is extended above the bench. To date, this hasn’t presented much of a problem since most work requires only a slight grip of the teeth at the bottom, or can be pushed against the wooden side of the stop.

After struggling unsuccessfully to get small, commercially made holdfasts (5/8-in.-dia. shank, 8 in. long, with a 4-in. reach) to grip, Tarule recently had a pair of hefty iron holdfasts custom-made according to Roubo’s description. One is 20 in. long, the other 15 in. long. Both have 1-1/16-in.-dia. octagonal shanks, which hold securely in 1-1/4 in.-dia. holes bored through the top of the bench and the front legs. The longer holdfast is used in the top, and the shorter one is used in the legs—at 15 in. long, it’s short enough not to hit the rear leg of the bench when set. Hand-forged by a local blacksmith, the pair cost Tarule $130.

A wooden hook screwed to the front edge of the benchtop holds the end of boards during edge planing. Shaped out of a piece of white oak, the hook accepts stock up to 2 in. thick.

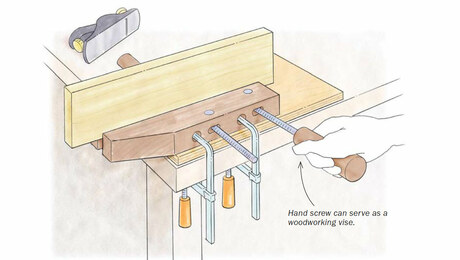

Tarule also built a modified version of Roubo’s optional leg vise. Where Roubo’s vise had no garter, Tarule added one. A slim, tapered oak wedge, the garter fits in a mortise in the side of the vise and engages a groove turned just below the screw’s head. It allows the jaw to retract as the screw is withdrawn. In hindsight, Tarule concedes a simpler solution would have been to bore a round hole in the side of the vise, then tap a dowel into the groove.

To keep the vise jaw parallel to the leg of the bench, Tarule installed a horizontal beam near the bottom of the vise. To stop the bottom of the leg from moving as the vise is closed, a peg is placed in front of the leg in one of a series of holes bored through the beam. To determine hole placement, Tarule laid out a grid of three parallel lines along the length of the beam, then drilled 1/2-in.-dia. holes at l-1/2-in. intervals along each line. The holes are staggered by 1/2 in. on each line to provide maximum flexibility of adjustment. For the screw, Tarule turned a hard maple cylinder on the lathe and borrowed a friend’s screwbox to cut the 1-3/4.-in.-dia. threads.

Battens—thin scraps of wood used in a wedging action with holdfasts and stops to provide additional grip—play a major role in Tarule’s workholding system. To gain flexibility, or to plane diagonally across a board, Tarule fastens a batten to the bench with a holdfast. The end of the batten pushes against an edge of the board, which is wedged between it and the stop. This process secures the work and enables Tarule to plane the entire board from one position. For quicker setups, the holdfast can also ride loosely in a hole, just touching one edge of the stock for slight lateral support.

Most modern workbenches have two main operational areas—the tail vise and the front vise. On Tarule’s bench, the focal point is where the stop, hook, and holdfasts convene. To plane the edge of a board, one end is jammed in the wooden hook on the bench’s front edge. Short boards are clamped to the left leg with a holdfast. To support a board that’s too long to be supported by one holdfast but too short to span both legs, Tarule attaches a 2×4 to both legs, using holdfasts. The 2×4 serves as a platform for a board of almost any length. Stock can be jammed in the hook, flipped end-for-end quickly as it’s worked, and replaced with another piece of stock—all without adjusting the support platform.

The ease and speed provided by Tarule’s workbench is a convincing argument on behalf of the simple bench. But is it really appropriate for the modern woodworker, who works with a variety of materials and tools? I know of only a few woodworkers who reject the tail vise and prefer to work on a bench as simple as Roubo’s. “I’ve done a lot of work on the bench,” Tarule says.” For my purposes, it needs to be adaptable to a variety of methods.”

Before adding the workholding devices to the Roubo bench, Tarule kept a Record vise mounted on one end—to handle the miscellaneous small holding tasks of a modern workshop. After unbolting it in honor of my research, he discovered that he missed it on several occasions. Clearly, the insights Tarule has gained into 18th-century woodworking won’t be his last. “I see myself quite seriously tinkering on this kind of stuff—spending the next ten years figuring out how Roubo used the bench.” Tapping the benchtop, he adds, “If I didn’t have to make money, I’d do it all the time.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in