Keeping Hand-Tool Cabinetmaking Fun

Israel Martin likes machines but prefers to work with hand tools. To avoid the tedium that can accompany working with hand tools, he simplifies his designs, using mostly straight lines and square corners.

Synopsis: Israel Martin likes machines but prefers to work with hand tools. To avoid the tedium that can accompany working with hand tools, he simplifies his designs, using mostly straight lines and square corners. In this Handwork piece, he describes his approach to working with hand tools, sharing what he has learned about himself as a woodworker and how that has enabled him to find the right balance between precision and speed.

I build furniture in a small workshop attached to my house in northern Spain, and I try to use only hand tools in every piece I make. I really do like machines; it’s just that I prefer to work without them. Over the years, I’ve discovered that working completely by hand requires not only a different set of skills but a different way of thinking as well. Like anyone making custom furniture, I need to consider where a piece is going to live, what its purpose will be, and of course the aesthetics of it. But because I’m providing the horsepower, there are extra dimensions to consider: How long will the build take? How complex is it? How can I make sure that I will have the same energy and enthusiasm at the end that I had at the beginning?

In preindustrial workshops, where furniture had to be made by hand, there were apprentices to take on the hard, repetitive jobs like jointing, planing, and ripping that today are routinely done in a snap with machines. Having apprentices enabled master craftsmen to keep focused on design, joinery, fine details, and finishing. As a maker who uses only hand tools, I have to be the apprentice as well as the master, and I plan each piece with that in mind. Knowing I’ll be doing all the jobs myself, and by hand, has led me to develop a specialized approach to design.

In preindustrial workshops, where furniture had to be made by hand, there were apprentices to take on the hard, repetitive jobs like jointing, planing, and ripping that today are routinely done in a snap with machines. Having apprentices enabled master craftsmen to keep focused on design, joinery, fine details, and finishing. As a maker who uses only hand tools, I have to be the apprentice as well as the master, and I plan each piece with that in mind. Knowing I’ll be doing all the jobs myself, and by hand, has led me to develop a specialized approach to design.

The satisfactions of simplicity

I firmly believe that the more you enjoy building a piece, the better it will be. Because complex projects done by hand can drag on and become tedious, I simplify my designs, mostly using straight lines and square corners. If I incorporate a curve, it might be a slight bend on the top or bottom of a chest. I avoid curved panels or drawer fronts that would involve lamination and require me to hand-dimension a lot of thin elements—a complicated and taxing process. To make my pieces catch the eye, I prefer to include details like small side drawers or inlays that are not just visually interesting but fun to make by hand.

I don’t draw measured plans, and I rarely build mock-ups. I rely on rough drawings and begin work on the piece with a quick sketch noting its overall height, width, and depth and the size of its doors and drawers. This gives me the leeway to change a piece as I go. It’s a little like working on a sculpture. If I make a mistake, or if the wood presents unexpected problems or opportunities, I can respond by slightly changing course.

|

“I prefer to include details like small side drawers or inlays that are not just visually interesting but fun to make by hand.” |

The question of structure in casework

Most of what I build is casework, and one of the first things I consider when designing a new piece is whether it should have a slab carcase or a frame-and-panel. Slab construction involves fewer parts and fewer joints, but dimensioning the pieces by hand is more exacting and therefore more time-consuming. To make for good joinery, the parts of a slab carcase must be precisely milled on both faces and all edges. A frame-and-panel structure, by contrast, is more complex, with more parts and more joints to lay out and cut. But milling the parts is faster, because only the frame parts need to be milled precisely. The panels can be flattened on one side and just smoothed on the other.

With these variables in mind, I normally pick slab carcase construction for boxes and small case pieces. But for larger casework, such as a big chest of drawers or a hunt board, I use frame-and-panel construction, which breaks up the milling over a long build and makes the process more enjoyable.

| From Fine Woodworking #313

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below. |

|

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Starrett 12-in. combination square

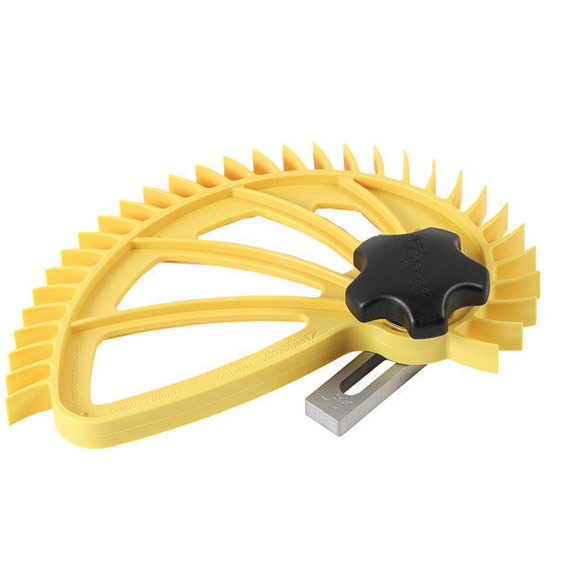

Hedgehog featherboards

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in