Peter Follansbee’s unplugged workshop

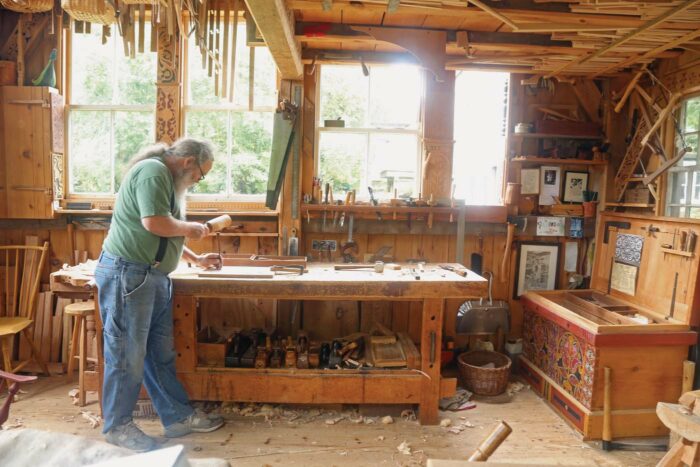

At just under 200 sq. ft. and without electricity, Follansbee’s shop suits the way he works.

Synopsis: Peter Follansbee does his woodworking in a freestanding timber-frame shop that’s just under 200 sq. ft. He only uses hand tools, so the shop has no electricity. A woodstove keeps the place warm in winter. The shop includes an 8-ft.-long workbench, a foot-operated pole lathe, an auxiliary bench, and hand tools on shelves and in chests, cabinets, and boxes. There’s also a loft, with storage for additional tools and for unused furniture.

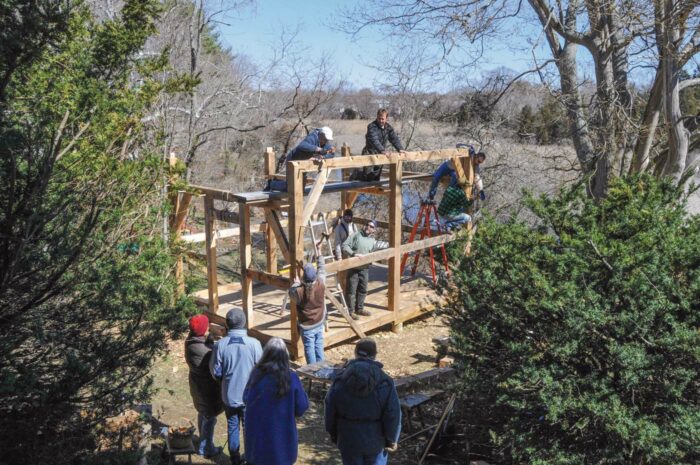

When the time came to build my shop, I started at the town hall. The woman there told me, “Under 200 sq. ft. you don’t need a permit.” I knew what to do from there. The first thing was to get my friend Pret Woodburn. He knows timber framing like I know joined furniture. Pret and I accidentally (that’s a story for another time) found a source of air-dried white pine 6 in. by 6 in. and 3 in. by 6 in. And in Jack Sobon’s book Timber Frame Construction we found a 12-ft. by 16-ft. shed, which would put me just under the 200-sq.-ft. maximum. We adapted a few things and built the frame by hand in 2015–2016. I remember the raising day as a highlight of my career, with friends and family working together. After seeing a short video clip of it, Drew Langsner wrote to say, “Congratulations, you’re one-third done!”

Over the next year we closed in the shop, added board-and-batten siding, installed tongue-and-groove flooring, and fit in more windows than we could have imagined. We fastened wood shingles to the roof and used shutters from a warehouse in Newburyport, Mass., as the doors. There’s a loft over the front half of the shop. Strips nailed to the undersides of its joists form racks for holding prepped chair parts—dozens of them.

My woodworking is an all-hand-tool affair, not out of a sense of snobbery or self-righteousness but from a strictly personal standpoint. It’s how I want to spend my days versus how I do not want to spend my days. I didn’t want electricity in the shop. Part of that reasoning is about lighting. Overhead lighting is not the most conducive to the carving that is central to most of my oak furniture. Raking light is the way to go for me.

A full tool chest

Just inside the door is a large tool chest. I based it on Chris Schwarz’s book The Anarchist’s Tool Chest. But I couldn’t bring myself to paint it a solid plain color, so I painted carving patterns all over the front and lid. Painting is slower than carving, it turns out. Dozens of times a day I’m in and out of that chest. Inside the chest are sliding tills with many of my carving tools in the top till, some chisels and various other small tools in the next, and a few bulky tools—such as some planes and an eggbeater drill—in the third (and deepest) till. Under those are braces, molding planes, saws, and a box of mortise chisels. The lid holds items such as small bits, awls, and a square.

An indispensable pair of tools stands beside the chest, right inside the door: a froe and club. These tools mostly get used outdoors.

The main workbench

Just beyond the tool chest, the main 8-ft. workbench is along the south wall. On a shelf under the bench are some boxes of small tools: rulers, mallets, a chalkline, cleavers, and more. There is one box that contains what I think of as “tools I hate”: wrenches, pliers, and screwdrivers. These are things I sometimes need but never have fun using. Farther along are most of my everyday wooden planes, a couple of jointers, a scrub plane, and a smooth plane. I have too many planes, so there are some duplicates. Bench fixtures—a wooden bench hook, homemade handscrews, and other things—collect in a jumble under there as well.

Above the bench and just below the row of windows are some tool racks for things like marking and mortise gauges, a few frequently used chisels and gouges, spokeshaves, and other tools that don’t have a specific home other than that rack. Attached to the back edge of the bench is a smaller rack with an awl, a square, a compass, and a miter square. Sometimes an odd chisel or gouge lands there too. Stuff hangs up: rulers, a strop and saws, chair-sticks, and patterns.

Wherever it fits is where it goes

Up in the corner beyond the main bench is a cabinet holding the all-important axes. There are two large ones, some smaller ones, and a hollowing adze.

One thing this small shop lacks is a place to store boards. As I rive, hew, and plane oak for joinery, I first stack it in the loft. Once it’s dry enough I stand it in a corner. It’s a horrible way to store material; it never stays neat.

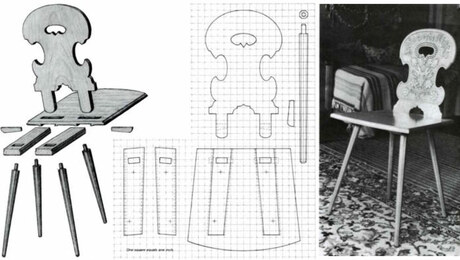

Way up high are baskets of peg stock (for pinning mortise-and-tenon joints) and pegs and wedges for chair-bending forms. Higher up is basket splint material as well as my stash of hickory bark for chair seats. And there are more and more patterns, or sticks. These are like carpenters’ story sticks; they have the turning patterns and joint spacing for things like joint stools and wainscot chairs, and all the patterns for my applied turnings. Most of these are based on museum pieces I’ve studied and recorded; some I’ve designed myself. They’re hanging everywhere in the shop.

Tucked under the roof are some chairs that aren’t in use—a couple of my early ones and two of Jennie Alexander’s, one of her first and one of her last chairs. There are more chair parts, some made by students in my last class and now waiting to be issued to the next class. My chair parts also go up there.

Throughout the shop there are small shelves tucked wherever I could fit them. These hold things like boxes of auger bits and scratch stocks, sharpening stones, painting materials, more planes, and goodness knows what.

To everything turn, turn, turn

Some of my work involves turning, and for that I have a wooden pole lathe I built with some friends in 1994. It sits tucked against the east end of the shop, and when I need it I pull it forward about 2 feet to give me room back there to tromp on the foot treadle.

The 12-ft.-long spring pole is up in the roof’s peak, almost 16 ft. above the floor. I have two different sets of beds, or ways, for the lathe. The shorter set is on it as a regular thing, and with this bed I can turn stuff up to 30 in. long. The longer set allows me to turn chair legs 48 in. long. I don’t want to turn anything longer than that. Opposite the axe cabinet is a similar one housing the few turning tools I use. Both of these cabinets are nailed to the wall and are only about 5 in. deep.

The 12-ft.-long spring pole is up in the roof’s peak, almost 16 ft. above the floor. I have two different sets of beds, or ways, for the lathe. The shorter set is on it as a regular thing, and with this bed I can turn stuff up to 30 in. long. The longer set allows me to turn chair legs 48 in. long. I don’t want to turn anything longer than that. Opposite the axe cabinet is a similar one housing the few turning tools I use. Both of these cabinets are nailed to the wall and are only about 5 in. deep.

When it’s not in use, the lathe collects things on its bed—chairs and boxes in the works, any small things that can fit. Chairs and baskets of offcuts find their way under the lathe. It’s an always-shifting collection of stuff.

Beside the lathe and under the turning-tools cabinet is a bookcase housing extra furniture books, some woodworking books, and, most importantly, notebooks of period works I’ve studied, along with photos and measurements I need to create reproductions.

An auxiliary bench

Along the north wall is an Ulmia cabinetmaker’s workbench I bought new in 1984. When I need to use a vise, this is the ticket. Otherwise, there are often projects in process standing on this bench. Stacked on the shelf underneath are more planed oak boards and more chair rungs. There are two toolboxes on the floor beneath it too; these come out when I travel.

One anomaly—a modern water-cooled grindstone—sits under this bench too, waiting to get pulled out every two or three months. An extension cord from the house solves the obvious problem that arises from this tool. That’s also the solution when I use a steambox or when Fine Woodworking editors come to shoot photos with lights.

Warmth

The corner opposite the tool chest houses a small woodstove for wintertime. In winter, the space around the stove is taken up by firewood. In summer, my shop gets larger because I can store things around the stove. The only insulation is under the floor, but the stove gets the shop warm enough except on the coldest days of the year. Then I turn to desk work in the house.

It starts outside

Most of my work starts outdoors: splitting oak logs apart and then hewing the pieces before bringing them into the shop for planing or shaving. The fixtures out there include a knee-high stump as a chopping block for axe work and a large tripod riving brake for holding stock when I’m splitting it with a froe. Several low benches round out this yard area. I use them for some rough work or for tool and stock storage as I work outside. The green log sections stand against a wall waiting to be pulled down and split apart. At the other end of the spectrum are piles of firewood stacked and unstacked.

Lofty aspirations

The loft is another story. I always wish it would function better than it does. Some of it works. There is a small chest of drawers full of occasional tools—things like fasteners, household tools, and other bits used only rarely. Some prepped stock is stacked up there too—more chair parts. Some furniture ends up there for various reasons—usually because there is no space in the house—but these are not things I want to let go. A carved chest that’s destined for my children one day now stores hand-pounded ash splints waiting for that perfect day for basket-making. My favorite carved chair got bumped out of the house due to space issues. It’ll come back some day.

There’s a tool chest up there too, which houses extra-extra tools. I’ve been whittling that collection down slowly. When I finally get through it I can also get rid of the chest. But its spot will get filled with something else.

—Peter Follansbee, author of Joiner’s Work (Lost Art Press, 2019), does his woodworking in Kingston, Mass. You can find more of his writing on his substack.

Comments

Peter is an amazing woodworker!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in