Randy Ogle, chairmaker and musician

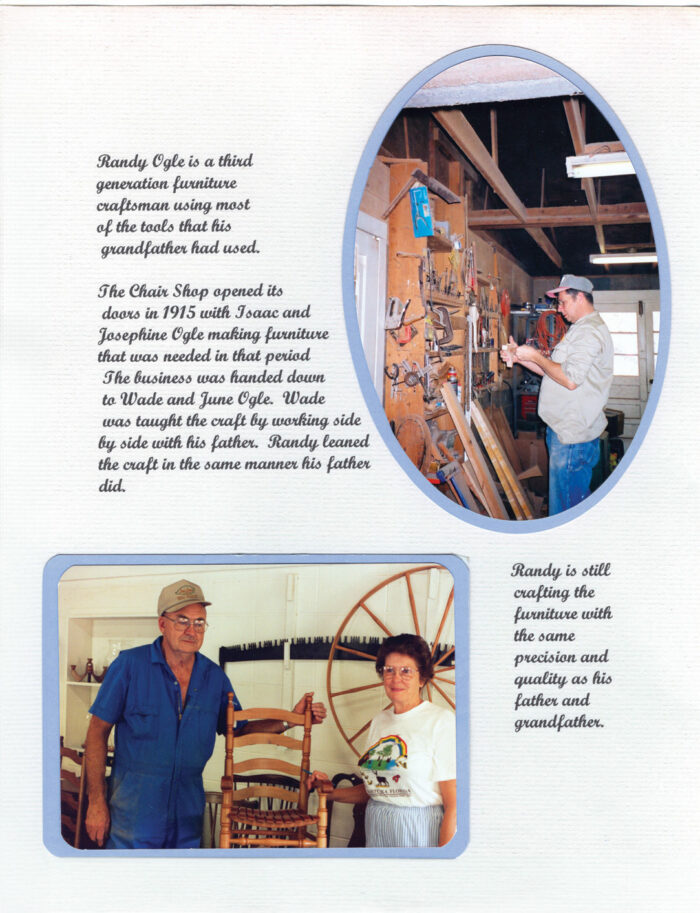

This section of Andrew D. Glenn’s book Backwoods Chairmakers: In Search of the Appalachian Chairmaker gives a glimpse into the life and work of Randy Ogle, a third-generation woodworker in Gatlinburg, Tenn.

“Mother always said I was smart enough to get into

chairmaking but not smart enough to get out.” — Randy Ogle

This is an excerpt from Andrew D. Glenn’s book Backwoods Chairmakers: In Search of the Appalachian Ladderback Chairmaker, available from Lost Art Press. This is an excerpt from Andrew D. Glenn’s book Backwoods Chairmakers: In Search of the Appalachian Ladderback Chairmaker, available from Lost Art Press.

SEVIER COUNTY, TENNESSEE – Before speaking with Randy Ogle, I guessed that he set up shop in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, due to the high traffic, spendthrift tourists and the people who had second homes in the area. It seemed an ideal location for a chairmaker, but it might not fit the definition of “backwoods chairmaker.” The town of Gatlinburg, though nature-themed, is anything but backwoods. Those sitting in traffic under the neon lights, just a few miles away from Randy’s chair shop, would be hardpressed to call this a rural, natural space. After a few minutes on the phone with Randy, I realized that what I knew of Gatlinburg was so small as to be almost inconsequential. Randy has family roots there that go back to before the Civil War, when Gatlinburg was named “White Oak Flats.” His grandfather, Isaac, started the “business,” though it wasn’t a business as such. There was no showroom or developed workshop, it was more like a shed out back where he worked. Randy and his father, Wade, continued the family efforts, making chairs and custom furniture to order. This shop, in the Glades area of town, was started by Wade about 1965. It was here before big Gatlinburg came to be. The town came to the chair shop, not the other way around. |

Randy invited me to visit. He has a wonderful tendency to be optimistic and hopeful when discussing challenging subjects. And he has a penchant for self-deprecation regarding his accomplishments. Don’t let that fool you. There’s wisdom in his words, delivered with equal parts humor and insight. As we discussed his family, his chairs and how he reached this point in life, he said I needed to understand one piece of information to appreciate it all. The chairs and custom furniture pointed to a better life. “One of the overriding, most common parts of living in rural Appalachia is: You don’t even know it, but you’re exceedingly poor. Abject, almost poverty. When you start with a base of nothing, anything you do seems like an accomplishment.”

The difficulty, he said, starts with the land and farming the landscape, with its steep hills and myriad challenges.

“The people impressed me because they were able to pretty much flourish under those adverse conditions,” he said. “My granddad was a farmer. Everybody was a farmer. You farmed to eat. But sometimes he’d have more than he needed, and he’d sell eggs. Somebody might want four chairs and he’d trade them for a pig. He might hear somebody say there was an upturn in what he called ‘the tan bark’ price. He cut tan bark for a year. But he was still a farmer. He had to farm to live.”

I interrupted. “Tan bark?”

“They called it tan bark,” he said. “You’d cut chestnut oak trees, in some regions it was hemlock. But you’d cut chestnut oak trees and strip the bark off of them, hauled the bark to the railroad in Pigeon Forge where the leather tanneries bought it … They used it to tan leather.”

Randy’s grandfather Isaac made his first chair at 16 and learned the trade from his aunt Mary McCarter Ownby. Randy suspects there were more chairmakers in the Ownby family line but does not have the genealogy records to show it. Regardless, Mary taught Isaac to make chairs. Isaac experienced profound changes during his life in Appalachia. And his woodworking changed, too.

“He built finished, progressive furniture just like anybody did,” Randy said. “But he actually saw it go from the completely rustic, handmade stuff to lacquered and delivered in Michigan; it was a pretty big difference. He experienced a lot more changes than I ever did.”

Isaac went from making shaved, rougher homebound chairs to lathemade. Maple was ideal: strong yet workable, plentiful and closed grain, which made scrubbing it possible.

Grandfather got a request for a walnut chair every once in a while. Used to building maple chairs. “White” is associated with clean. If you live in rural Tennessee, dirt was a problem, cleaning was a problem, (it) was part of your big effort. They’ d take sand out of the creek and make a broom out of brush (tiny hardwood twigs of hazelnut or rhododendron, lashed to a handle) to scrub the floor with. To get it bleached out, cleaned up. (So with a) white chair, you could wash it down with sand and it was pretty clean. They used maple because it worked good, was strong, and it looked clean and neat.

Now the first one who ever ordered walnut chairs, Grandpa said, he went out and cut down a big walnut tree and split it and just split the sapwood off and made it out of the white sapwood. The black wood was left somewhere else. He just thought, “Who would want that black chair?”

A couple other makers were known for their unfinished furniture and the ability to clean it. Some, such as Chester Cornett in his earlier years, or the makers of Cannon County or Mark Newberry working today, expect the purchaser to add the finish. Or they charged extra to finish the piece. Years ago, adding a protective finish was uncommon. The early chairs that Isaac made did not receive a finish, and Randy said the chairs were lucky if they received a paint job later in life.

Somebody else, somebody asked him for a set of chairs with an oil finish on it. Part of the Appalachian culture is that you’re proud and pretty stubborn. He [the maker] just grinned and nodded at him and said, “I didn’t know what kind of oil to get. I went and bought a quart of motor oil.”

I’d like to saw what they looked like a year later.

Randy’s shop is situated on a quiet road, now marketed as the “Arts and Crafts Loop,” just off a main throughway into Gatlinburg. It’s a combined shop and showroom, with the shop space taking about two-thirds of the building. Randy grew up working in the shop with his parents, helping his father Wade make chairs and fill orders, while his mother, June, worked the showroom.

Wade took the small family business and grew it. The Gatlinburg area was expanding, and Wade saw the possibilities with chairmaking and custom furniture. Randy said he admired his father’s ability to progress forward, both in business and life. Wade went through incredible changes during his time, from outhouses to plumbing, walking everywhere to automobiles, and mule teams to machinery. Many of those changes bracketed Wade’s time in the U.S. Army.

Randy explained how he had choices the previous generations didn’t, yet chose to remain in the business, while Isaac and Wade’s pursuit of better lives led them into chairs.

If I had been born in 1900, I would have farmed, followed a mule, cut tan bark, whatever it was to squeak by. By the time I was born in ’53, Dad had a car and a public works job, the way they put it. So I never had to depend on whether the hens layed or not to eat breakfast. There was something there. So I was more affluent and could pursue what I wanted to instead of barely squeaking by, subsistence living. We were kind of the first generation around here that could deviate much from the pattern. Dad was really the first one. Partly because the time in history, and also because so many people left here to go into the Army in World War II.

If you show somebody a better way, they are awfully likely to take it. I don’t know why I didn’t, but I didn’t. I’m about as smart as a normal hillbilly. Before you can make a decision to stay with something old, you have to be affluent enough to afford to do it. My generation was affluent enough to choose what we wanted to do.

There is a hint of disappointment intertwined with pride as we discuss his time in the shop. This comes from Randy’s proclivity for introspection and his ability, at 70 years old, to look back at the possibilities of life. He was not predestined for a life of chairmaking. He “looked around” as a young man (he thinks everyone does something similar) before returning to the shop to work alongside his parents.

I think it was a lack of choice when I was young. This was successful enough, you just keep doing it, but you’re always looking for something better. One day you just realize, “I don’t want nothing better.” That usually comes later in your life.

But yeah, for years, I was working here with Dad, and we were making money, making furniture and everything … making a mess. But if I got offered for a good job, I’d a … but I’d probably wind up come back. But that’s the formative years. I don’t know about you. When I was a kid, even in my 20s, I don’t know if I wasn’t mature enough or there was too many things to think about, but I didn’t really pick what I wanted to be. You always pursuing something that looks better than what you had. Did you ever notice that in your own life?

Eventually, you get tired of chasing stuff, and you’re alright where you’re at so you stay there. And with me, it just so happens that I’m here, and I cannot imagine doing anything else. If I didn’t do this for a living, I’ d have me a shop out behind the house to piddle with. That or fish.

Randy knows there are other options. He can drive three miles and be in the center of a tourist town filled with jobs and the ability to make a good living. There are opportunities to improve one’s lot in life. It was asking too much of chairmaking to expect a continued financial progression. Chairmaking has its limitations.

I feel some of that weight as Randy describes why he hasn’t encouraged his daughters to continue in the family business. They know the work, having started in the shop once they were old enough to rest on a packing blanket while Randy worked. They grew up in the shop, sanding parts or finishing furniture one day, then helping out in the showroom the next. Whatever work needed done, they did it. But:

There’s no money in it. I didn’t advise my daughters to take the shop over, and that’s why. They’d have been as happy as I am, and I consider myself blessed. But you’re committing them to 60-70 hour weeks for maybe $20,000-$25,000 a year, and it’s hard to make it on that now. That wasn’t too big a deal in 1980; 1990 started to get tight. Now I think I’d qualify for free lunches if I went back to school.

The Ogle Chair Shop does not have a single chair style. There is a Queen Anne side chair sitting in the showroom, along with turned post-and-rung chairs. Randy filled customer requests of all styles over his career. But the chair they make the most, and the one Isaac started with back in the 1920s, is the traditional post-and-rung side chair. Isaac shaved it, Randy now turns it. We focused on the ladderback during the visit. Randy and his friend (and part-time shop help) Pete Alcott diligently wove seats while we discussed the making process.

|

|

I tried to stay out of the way. (A fourth person was in the shop during the visit, Mr. Charles, who played bluegrass and country on the guitar as Randy and Pete wove seagrass. The shop, once Randy semi-retired, has become a local hangout. Pete considers the shop a version of the early general store. There’s daily music, along with a Friday-night session that draws a rotating group of musicians.)

We start discussing chair details. Randy supposes that the patterns he uses today were created sometime after the Great Smoky Mountains National Park came in, right around 1940. The park attracted visitors, and the town took off.

“Each shop had what we called a turning pattern, just a ring placement and shape, specialized to the customer,” he said. “Prior to public sales, there were very little ornamentation done on anything around here. It was utilitary, and that was it.

“I know this probably isn’t going to impress a lot of people, but by using those forms, that stick pattern, I can make a chair today that matches one my grandfather made in 1958.”

I asked about the most critical details in chairmaking. I ask each maker this question, and most respond with the importance of dry rungs. Ignore it and the chair fails. So it piqued my interest when Randy took the question in a different direction. Properly seasoned rungs are implied in his response.

I don’t know that there is a critical detail. For me, the critical part of making a chair is a durability as an end result. The aesthetics is a very close second place. If you take the chairmaking in the sequence that I have been taught or arrived [at], I’ve changed it a little bit from what Grandpa done and Dad done, changed some of my boring angles, changed some of my sizes. But if you take that into consideration, if you do each step properly, there’s not one step anymore or much less important than any other one. So there’s no one single detail above appearance, and it’s a secondary detail, so durability and appearance roll together in my goal.

You can make an ugly chair and make the best chair in the country. Aesthetics are just aesthetics. You can make a bad, ugly chair, splinters on it, and it will still last 100 years. It all dovetails together. The aesthetics are important. I just simply like the looks of a well-made, well-finished piece. Gives you a pleasant feeling just to touch it if it’s well sanded. I don’t like flashy, loud, shiny finishes as well as a soft, satiny, smooth finish. There’s just a pleasure in touching or feeling or using a well-made, well-finished piece. And I can’t separate that from … I can’t separate that in my mind to say it’s more important than the quality. If the pleasant portion of the experience is not there, then people won’t ever experience the quality because they won’t sit in it. So you can’t really separate the two, if that makes sense.

The process of making the chair has changed little since Isaac started making them. The wood has changed. Walnut is far and away the most popular choice with Randy’s customers. Light-colored woods, such as maples and ashes, are seeing an uptick in popularity right now, but Randy doesn’t expect that to hold. It’s a fad and will soon fall away.

One change is in how Randy gets material. He does not cut the timber and split the parts. He buys 2-in.-thick slabs, which air-dry outside his shop under a covering to keep the sun and rain away. But the most noticeable change is in seating. Early Ogle family chairs came with a corn-shuck seat. Randy can twist and weave that seat, but cannot justify the time it takes to put one in. So he uses seagrass and the same basic seat pattern. Still natural and the same Ogle pattern, without the excessive time and energy.

Randy likes the appearance of the seagrass seat.

It’s my seat of choice now. I don’t think there’s a better seat than a [corn] shuck seat. I simply cannot put them in fast enough to sell them. Most other seats are not nearly as durable. In the case of Shaker tape, and it’s a killer seat, it’s even an attractive seat, but it is a cloth webbing. They tend to stretch and the seat “saddles out” quite a bit. If the seat saddles too much the rungs inside the seat start to put pressure on your behind, and it can get uncomfortable.

Randy’s process for making chairs is much the same as his predecessors. It starts with milling and material prep. Randy considers strength and durability critical, but only to the extent that a side chair needs it.

“We call a post a 2×2. It’ll actually dress down to about 1-3/4-in. cylinder,” Randy said. “I use … Grandpa always did, Dad always did …3/4-in. tenon. That’s the part that drills into the other part. One reason for the 1-3/4-in. is that you’ve got two 3/4-in. holes going in. You’re cutting a lot of that out. Now, you could go down to 5/8-in. tenons and really not notice a big difference. Go down to 1/2-in. tenons, and you start to worry about people leaning back on it. The number of rungs in a chair makes it a lot stronger or weaker. Most of mine has three rungs on each side and two in the front and back. That gives you … When you count the back slats, the back slats add a lot of strength to the back and none to the front.”

I follow that up with a question on pinning the slats. Plenty of chairmakers do it, some even make it a design feature. It’s a way to tie the parts above the seat together and a way to add more strength to the entire piece. I do not notice any pins on Randy’s nearly completed chairs and ask whether he will eventually add them.

He stressed that with this design, the strength is with the rungs. The slats hold tight as the posts shrink around the slats.

Well, if you use greenwood, they grip down until the pin is unnecessary. The pin, or a nail, usually only holds a chair until the glue dries or the posts starts to shrink.

What I was about to say, if you’ve got 10 dowels in your chair, that gives you enough to start being a good-quality chair. A 12-round chair or a 13-round chair is marginally better but, like we said a minute ago, a chair that will hold 3,000 pounds when people weigh 300, what does it matter? You can put four rounds in the front of a chair, and it don’t add much strength.

When you look at a chair, with me leaning back, all your load is right here on these tenons [pointing to the side rungs entering the back posts]. It’s mostly on the back. You’ve got six holding him up, with 3/4-in. tenons, it’s a pretty strong chair. Six total. Now if you put four rounds in it, you’ll start to notice a little bit of looseness after a few years. But you could put nine on each side and it’d just look like a ladder. It wouldn’t be adding much more durability.

Randy’s tenon-cutting technique was also unique. It is a variation on approaches that other chairmakers use. He cuts the rungs to length before taking them to his tenon cutter, which is mounted on the lathe, complete with a stand on the bed to hold the rungs parallel to the cutter. A wooden plug in the cutter stops the tenon at the correct length, approximately 1-in. long. The plug has a pin in the center of it to mark the center of the tenon. After cutting all the tenons, Randy takes the rungs back to the lathe and turns the taper.

Next is sanding. Randy thinks this is where amateurs get it wrong. Amateurs greatly overestimate the importance of sanding. Extra sanding (going through multiple grits, from coarse sandpaper to finer ones) is not worth the time and effort. Randy sands his chairs with #80 grit, or some near equivalent.

To my surprise, the scratches were only noticeable with a close examination (but who else is going to lie on the floor to examine the rung scratches?). The chairs have a nice, soft appearance once Randy adds his oil mixture.

Randy’s given plenty of thought to pricing and sales. He knows his community, what he can charge for a chair, and the type of life this profession affords.

Randy truck farmed earlier in life, following the paths of Wade and Isaac, growing his food to live while the chair income covered expenses. His daily routine for those years was: work at chairs and furniture until 5 p.m., come home for dinner, then work the farm until dark. And while it was a lot of work, Randy was no outlier; his neighbors worked just as hard as he did. It is with that lived experience that he approaches the marketing and sales side of the business. When you work that hard for your money you don’t typically spend it frivolously.

I may be … well, I know I’m uneducated, and I’m quite naive. The first thing, in my opinion, you can do to stimulate sales is your pricing. Well, it’s so low now that there’s not much more give. You might double it or triple it and it wouldn’t affect your sales [income] but you wouldn’t have very many customers.

The biggest thing is promotion. And you need a more visible, accessible location. Again, I can’t see spending that kind of money without a positive return, pretty quick.

He knows his options if he wants more sales, but he’s not interested at this point in his career. He could advertise more, that’s one option. He knows where the tourists are, and they’re not coming back down his road much, so he considered relocating closer to the main throughways into Gatlinburg. But those business expenses would need to pay for themselves quickly, and Randy does not think they are justified right now. So he stays put and keeps his expenses as low as possible. As we spoke about the business side of things, Randy crystallized his current approach to marketing:

“Maybe it’s because I just don’t give a shit,” he said.

As with other makers, Randy struggled to get good money for the work that goes into the chairs and custom furniture. The making is the easy part. It is the selling that is difficult. He distrusts a heavy-handed sales approach. Either the customer wants it or not; he isn’t going to drive them into the sale. His philosophy: “Make it good enough where people will buy it on their own.”

He knows the nuances of pricing. The rates he charges are a balance between what he needs to survive and what the customer will pay. The hope is that the two are aligned. If not (as with the corn-husk weaving), then there is a decision to make about doing that work.

“In order to keep the shop open, I have finally arrived at a shop rate of $35 an hour labor rate plus materials,” he said. “And that averages around $50 hour. Now, on some things you might make $75 an hour for four hours once a month. Then again, you might make $10 an hour weaving seats for three days. With that work you can’t hardly charge $50 an hour … You just have to eat it.”

At these prices, he stays as busy as he wants to be:

- Side chair, no arms, walnut or cherry – $320

- Side chair with arms – $400

- Side chair, maple – $290

The challenge with pricing is with customer expectations. There are lower-priced (mass-produced) furniture options all around for customers, so the price tags in the Ogle showroom surprise many of them. They do not know the work and effort that goes into making the chair.

Really, the price of chairs bought from an individual craftsman at the “exalted” price … My rocking chairs average around $1,000. That reflects … you might not believe this … people looks at a $1,000 chair and think you’re getting rich. That reflects anywhere from a $200-$250 cash investment (materials, supplies and overhead) and about 40 hours work. So you take $200 off of a thousand … that’s $800 a week. That’s decent money, but it’s not rich man’s wages. If they want a woven seat, then you stretch that to six days so your money’s a little less.

Randy’s working less than he did years ago and is nearing full retirement. I ask about the shop once he’s done. What would he tell someone who wanted to follow in his path?

“I’d certainly do all I could do to help them if they decided it, but I wouldn’t encourage somebody,” he said. “Now if somebody sees this as a gold mine, then I’ll make it easy enough on them to do it.” But things have changed over his life in the shop. The hours needed to build are just as long, but the sales are tougher to come by. The income needed to sustain a couple of people just is not there right now.

“Back in the ’60s, if you owned a shop, you’d have two or three people working for you and be considered ‘semi-successful,’” he said. “Dad built a house and had it paid for in 12 years out of this little shop. That was in 1965. But in 2020 …”

We dropped by Randy’s shop mid-morning on the last day of our visit to return a collection of his family’s pictures. Our entire family is in the car, though only I go in because our children have long grown tired of hearing chair stories.

I hear Randy’s guitar before I enter the shop. Randy and a friend are having a session. I’m interrupting. They play another and quiz my knowledge of the songwriter. I feel that I should know it, but this lays my ignorance bare. I don’t even know enough country music to form a guess. The answer: Hank Williams (and I make a vow to always guess Hank Williams or Loretta Lynn from now on). They don’t hold it against me. I promise to stop back through the next time I’m near. Apparently I have taken too long. My daughter appears in the shop, not to join us, but to pull my arm toward the open doorway.

She has had enough chair visits and has hopes to reach a swimming pool by early afternoon. We drive east, toward North Carolina.

|

|

My next chance to mull over the visit was after we checked into an equal-parts charming and sketchy downtown hotel. I remained awake to process the Ogle Chair Shop visit. I plan to meet another maker in the morning, so this was my chance to write down final impressions before they are mentally washed away.

Looking through my notes left me with an impression of Randy’s contentment. Content with work—the chairs, the shop and farming. Content with life and the music he shares with friends and visitors alike.

I think through our conversation about being a generational shop and whether there is extra pressure to stay in the family business or in the continuation of it with the next generation. Randy did not feel the pressure from his father—or if he did, he did not share it. And he put no such expectation on his daughters. The early generation of Ogles used furniture and chairs to make a better life for themselves. Randy is not sure the shop option is best for his children. He looked around before coming back and dedicating himself to the shop. But his daughters have taken a different path. Randy is content with that. Possibly relieved.

So the shop may close someday soon, whenever Randy decides to fully swap out the turning tools for his guitar and fishing pole.

But “close” isn’t the right word. It’s too simple, often carrying a discouraging tone. This chair shop changed the trajectory of the Ogle family while producing beautiful furniture. To “close” is hardly adequate to describe what’s happened here.

I imagine the shop doors will remain open with Randy just as welcoming, even after he retires. The hum of chairmaking will be replaced by bluegrass chords and storytelling. It may become a community spot. A place for conversation and music.

If you stop by someday mid-song and Randy quizzes you, please guess Hank Williams on my account.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in