A Sycamore Surprise

Interlocking grain makes surfacing sycamore difficult, but Blake Davis still encourages you to try it.

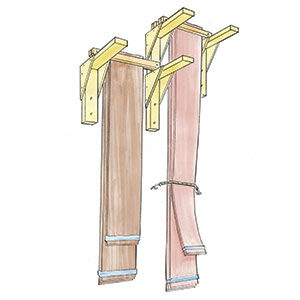

Like a lot of romances, my relationship with quartersawn sycamore began with a sideways glance. Then it got complicated. I was visiting Whispering Pine Farms in North Carolina, a small farm-based operation that specializes in sawing slabs, large timbers, and quartersawn lumber. Scott Smith, the owner, had left me to peruse the planks, which were arranged vertically in aisles that looked like caves of wood.

In one corner, an eruption of ray fleck and flake caught my eye. The figure was so dazzling I couldn’t see the vertical grain. Oak, I wondered? I removed a few of the boards. Couldn’t be. The grain was too fine, and there were pastel tones of orange, red, and yellow. Whatever it was, I wanted some. “That’s sycamore,” Scott said, when he returned to measure the boards I had chosen.

After that purchase, it took me a year to find a client interested in this lesser-known wood. Then the drama began. When I started milling lumber for the cabinet I planned, little chunks seemed to eject spontaneously; it was tearout in the extreme. Sycamore, which is sometimes called American lacewood by old-timers, has interlocking grain. No matter the direction you cut, you always work against some of it. If I’d had a helical head on my old Minimax jointer-planer, it would have helped. But I found I was able to remediate some tearout with lighter, skewed passes on the jointer.

Typically, after jointing and planing, I use hand planes to remove the machine marks. That’s what I did here. Again there was tearout. Placing the chipbreaker at the very edge of the plane iron, so just a hairline of blade was visible, helped. To tame the remaining tearout, I grabbed my card scraper. That worked to remove the tearout, but it left a fuzzy, stringy surface.

I repeated my workshop mantra: “I will not throw tools. I will not throw tools. I will not throw tools.” I spent a few minutes at my sharpening station and returned to work. I find scrapers often produce poor results on soft or medium-soft woods like sycamore, but if they’re extra sharp, devotedly square, only lightly burnished, and presented to the wood at a skewed angle, they will give a clean cut. Voilà. Now the sycamore looked stunning, even more so after light hand-sanding to a high grit.

According to my current supplier, C. P. Johnson Lumber in Culpepper, Va., sycamore lumber is not widely available mostly because sawyers find it difficult to source and complicated to mill in a way that yields good figure. And sycamore, a member of the maple family—it’s sometimes called Virginia maple—is similarly prone to discoloration when drying.

Yet there’s a strong case to be made for quartersawn sycamore, even beyond its spectacular looks. The wood is supremely stable (though only when quartersawn). The trees are abundant in the eastern U.S. They grow quickly and become massive—so big that some early Colonial settlers lived in the hollowed-out trunks of giant sycamores before building their primary shelters.

My advice about sycamore? Beg your supplier to be more adventurous. Don’t let that interlocking grain deter you. Quartersawn sycamore has its challenges, but so do other excellent woods. Sapele, for instance, with its interlocking grain, is similarly prone to tearout. But don’t buy sycamore plain sawn. It’s just … plain.

So get out your scraper. Sharpen it judiciously. And set to work with sycamore. In the process, you will learn how to deal with any figured wood, if you don’t know already. And perhaps you’ll begin an affair of your own.

—Blake Davis builds furniture in Richmond, Va.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in