James Krenov, Master of the Handmade

He delivers a message of intimacy and excellence in furniture, in print and in person

Contributing editor Jonathan Binzen wrote this profile on James Krenov (1920 – 2009) in 1996 for Home Furniture magazine.

James Krenov’s diminutive cabinets cast some of the longest shadows in contemporary furniture. Personal, precise, modest in mood as well as in scale, they have been widely exhibited and extravagantly admired. Collected by monarchs and museums, they rarely sit for long unsold.

Krenov’s influence on other furniture makers has been profound. In his four books and through his teaching he has introduced a poetic approach to one-of-a-kind furniture making that has changed the way many woodworkers think about their materials, their tools, their craft and their lives. But Krenov’s success and influence have not been without controversy. People find him gruff as well as gentle, maddening as well as moving. And for all his exposure, he remains something of a mystery. But while it is unclear what the legacy of his teachings will be, it’s likely that when history sifts out our century, some of Krenov’s cabinets will stand among the finest furniture of our era.

Meeting the man

Krenov’s furniture is an image of his extraordinary upbringing. He was born in Siberia in 1920, the son of Russian aristocrats on a transcontinental trek in search of adventure and a new life. Over the next decade his family would live in Shanghai and in remote villages in Alaska before settling in Seattle.

|

|

| A global voyage starts in the Arctic. In 1923 a three-year-old James Krenov sits on a boat left behind when floodwaters receded from the tiny town of Sleetmute, Alaska. Born in Siberia, he has since lived in China, the Alaskan territory, Sweden and the United States. |

From his mother, once accustomed to having her clothes made in Paris, Krenov inherited “the need for excellence and the genuine and a kind of reverence for fine things.” But there is little of high fashion in Krenov’s furniture. His style was formed more by exposure to the utilitarian crafts of the towns where he grew up: fish traps, baskets, knife handles, snowshoes, boats. “I was brought up on aesthetics not as a topic, but as ethnic art or craft, as nature,” he says. “I’ve spent most of my life sailing, being in mountains, on beaches. If I have any aesthetic education, it is a synthesis of the lines of a fine boat, the way a branch bends in the wind.”

Krenov remembers making his own toys as a child. As some of his mother’s native Alaskan students gathered to watch, he would make toy airplanes, boats, a tiny crossbow that shot arrows made from kitchen matches. When he gave them away, he pleased himself as much as his playmates.

|

|

| Good hands. An only child raised in remote villages, Krenov became his own toymaker. |

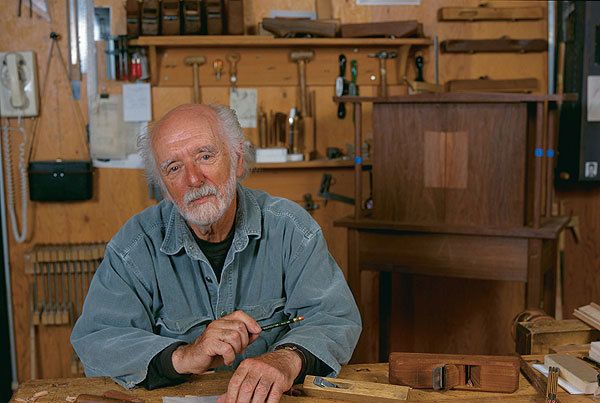

Now, at 75, after a lifetime of making furniture, Krenov sits in the sun behind the small school in Fort Bragg, California, where he has taught and built furniture for the past 15 years. His voice is high and raspy and he plays it like a reed flute. Talking is an art with him; a listener soon learns not to interrupt too often, just to sit back and let the dazzling stream flow. Thinking of those toys he made and gave away, Krenov looks down at his fingers, momentarily at rest on the picnic table. “I’ve always had strong hands,” he says, “good hands.”

Malmsten for a mentor

In his mid-twenties, Krenov left Seattle for Sweden, more or less on a whim, and then stayed for 30 years. There he found his life’s work and an imposing mentor, Carl Malmsten, then the foremost furniture designer in Sweden.

|

|

| The master’s apprenticeship. Krenov found his vocation here, in a school run by Swedish furniture designer Carl Malmsten. |

Krenov says that Malmsten had a very strong personality and was an overbearing teacher: “a patriarchal, holier-than-thou” figure “who knew all that was right and all that was not right” and “gobbled up young, gullible students.” But Krenov credits Malmsten with having “sound, simple, straightforward” ideas about furniture, an excellent eye and a nearly magical way with lines. “He was forever trying to train us to draw beautiful lines,” Krenov says, to draw them freehand, “to get a line that is subtle, yet definite. One that hasn’t been forced, it’s been coaxed. And some of the coaxing is left in.”

In a look through one of Malmsten’s catalogues, one recognizes forms and motifs that underlie many of Krenov’s cabinets. If Krenov hasn’t strayed far from his roots, perhaps that is because his exploration has been inward rather than outward. “I’ve never believed that you have to be all that inventive,” he says. “Form is only a beginning.”

The tactile cabinet

From across the room, a Krenov piece is calming rather than exciting. Its colors are muted, its lines limber. But encountering one of his cabinets is hardly a passive experience; once you are within arm’s length, the work invites interaction.

|

|

| “The quiet object in unquiet times.” In his spalted broadleaf maple and red oak cabinet Krenov reaches his goal of provoking peaceful contemplation. |

Reach for a door pull and you notice the texture left by his carving tool. The pull is small and shaped so you naturally grasp it between thumb and forefinger, so you use the muscles of your hand rather than your arm to open the door. The spalted maple panels in the doors curve right out of their frames at one side, as if to raise an unanswerable question.

Everywhere you move your hand or eye there is something to explore. Even the pegs that support the shelves are tenderly carved. Every inch of the cabinet counts. “Within the little details,” he writes, “there is a search for meaning.”

|

|

| An affair of the hand. With beautifully articulated junctions, Krenov brought joinery to the level of sculpture. |

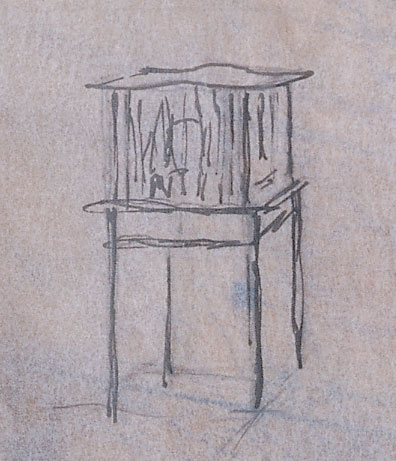

Krenov doesn’t divide the furniture making process into design and construction; instead, he interweaves the two. He starts with little more than a doodle, a rough sketch as small as a thumbprint, though just as telling, and plunges into the building.

|

|

| It begins at the bench. His hand skills give him the freedom to improvise on the path from his tiny sketches to his finely detailed cabinets. |

He makes decisions as he goes, responding to the color, grain and working characteristics of the wood and to the way the overall forms and details of the piece interact as they emerge. Krenov calls this way of working “a fingertip adventure.” Tom Hucker, a furniture maker in New York City, compares Krenov’s method to that of a watercolorist: “It’s a very naked way of working. Very pure. You don’t cover up mistakes. One try and that’s it. Every brushstroke is revealed—nothing is hidden.”

From furniture into literature

Shavings curl from the plane in my hands. …(M)y contentment is bound by the white-washed walls of my little cellar shop, by the stacks of long-sought woods with their mild colors and elusive smells, by the planked ceiling through which I hear the quick steps of a child—and yet it is boundless, my joy. The cabinet is taking shape. Someone is waiting for it.

|

|

| “A slight curve can be a marvelous message,” Krenov says, “it doesn’t need to be a pretzel.” He proves it in this lithe showcase cabinet in pear with hickory legs and frame. |

|

|

| Why is it wedge-shaped? Krenov needed this narrow door wide at one side to mount knife hinges but tapered it to keep it from looking clunky. |

There wasn’t a single construction drawing in A Cabinetmaker’s Notebook, Krenov’s first book on furniture making, and no advice on when to use what kind of joint. But it was as explicit a manual as a woodworker could find. It described a seductively unhurried, uncompromising way of working that promised full engagement in life and work without much direct engagement in society.

|

|

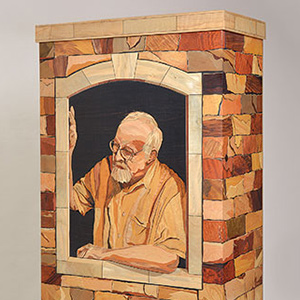

| Graphic design. In a stark departure from his typically sculptural pieces, Krenov here (and in other recent work) creates graphic effects on flat surfaces with abstract patterns of veneer. |

The response to it was overwhelming. Jim MacDonald, a furniture maker in New Hampshire, speaks for many others when he says, “From the second I opened that book I was a woodworker. It changed the course of my life.” Curtis Erpelding, who builds furniture near Seattle, remembers that after Krenov’s first book came out, woodworking became “a religion, a way of life. He offered a completely different vision of what it meant to work wood and to be a furniture designer.”

For some, the impact of Krenov’s work was almost too strong. “It was so powerful and so appealing,” Erpelding says, “that it could have a negative effect in terms of trying to find your own voice.” And although the graceful prose of Krenov’s books made it easy to imagine the life he described, many people encountered financial problems when they tried to emulate that life. Bob Ingram, a Philadelphia furniture maker, says he found Krenov’s books “way too romantic. It was all right for him, he found a way to make money from it. But I saw so many people embrace that romance and fall flat on their faces.”

|

|

| An open fire. Krenov named this cabinet Fire and Smoke for the figure in its pearwood veneer; alerce is the framing veneer and the drawer fronts are pernambuco. |

Krenov acknowledged the quandary, going so far as to call his third book The Impractical Cabinetmaker and referring to himself and those who worked in a similar way as amateurs. Acknowledging the problem didn’t solve it, however; those influenced by Krenov have all had to find the balance point between his poetry and life’s practicalities. John Gallagher, a recent student of Krenov’s who finds himself making flutes instead of furniture, is philosophical: “Jim teaches creative writing. He’s not teaching how to write for advertising or for newspapers.”

|

|

| Details carry DNA. Custom drawer pulls carved in pernambuco reflect the rigid lines of the cabinet. |

A private man goes public

The success of his books brought Krenov increasingly out of his Swedish cellar and into classrooms and lecture halls around the world. In his speaking as in his writing, Krenov was able to string together strong images and moving anecdotes in a seemingly offhand way. People flocked to hear him. Describing one lecture in New York City, he says, “Believe it or not, 900 people showed up. It was like a rock concert. I was scared to death. I went out on the stage and took the mike and flipped the cord—you know, the way the singers do—and I said, ‘Is this the way they do it?’ Everybody laughed, so we were off and running.”

In 1981, Krenov founded the woodworking program at the College of the Redwoods, in Fort Bragg, California. Students come from around the world and from a variety of other endeavors to attend this little community college program. Prior accomplishment in music or painting is as likely to get you admitted as skill in working wood. It is a measure of the quality of instruction that at the end of nine months even students with no previous experience in the craft turn out work at an extraordinarily high level.

|

|

| Rhythm in browns. Krenov pairs woods whose colors enrich and define one another. Here a Honduras mahogany frame encloses yaca doors and panels. |

The school’s atmosphere is one of intense concentration and dedication. Students describe the experience as one where the rest of the world falls away, providing a rare opportunity to do the very best work they can. “I can’t say enough about how much he pushed me, and raised my sights toward what was possible,” Bill Walker, a Seattle furniture maker, says. Les Cizek, another former student, had a long and successful career in business before attending the school. Describing Krenov’s teaching, Cizek says, “He’s got a gift for making you see things. We all can walk through a garden and say, ‘That was a great garden.’ But if you go through with the right person, you come out with a different appreciation for form, arrangement, color—your way of seeing has been enhanced.”

Just as Krenov’s readers must make their own peace with the conflicts his message raises, his students have to confront the contradictions of his personality. Krenov’s intensity and unwillingness to compromise, the very qualities that fuel his furniture, can make interaction with him difficult.

Krenov acknowledges there are times when “you get into a corner and you become adamant or people interpret you as intolerant or opinionated; and maybe sometimes I am. It’s a negative side of my person. But the positive other side is that I have strong views.” Krenov feels that anyone who works alone and makes a life of self-expression must rely on the strength of his convictions. “You’ve got to believe in something, something you won’t compromise on.”

|

|

| Toolprints. A faceted rosewood pull asks to be opened with a fingertip. |

The style of Krenov’s furniture is as strong as his opinions, and the College of the Redwoods program has been criticized by some outsiders because student work tends to look like Krenov’s. Les Cizek concedes that it often does, but he thinks it only makes sense: “If you were studying under Beethoven, you wouldn’t play jazz riffs. You’d learn what he had to teach you. Later on you could take what you learned and develop your own voice.”

A powerful grip

Amid acclaim and controversy, Krenov keeps making furniture. As the shadows grow longer, he sometimes finds himself “counting from the other end, thinking old man’s thoughts.” But he shows no signs of slowing down. He still works seven days a week and some of his recent cabinets, veneered in abstract patterns, show a daring new direction in his work. He walks daily on the beach with his wife of 45 years, Britta, and plays tennis whenever the weather is fine, easily holding his own with players half his age. Describing the pace of his life, Krenov starts to say it might make sense to take things a little easier. But then he admits he can’t imagine it. “I want all my life to be active. There’s a clarity that comes from really being taken into your work. It pulls you into a sense of balance that you don’t find anywhere else. I’m myself when I’m working.”

Black & white photos: Courtesy James Krenov; All others: Jonathan Binzen.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Blackwing Pencils

Circle Guide

Suizan Japanese Pull Saw

Comments

I confess I don't like all his work or even claim to understand it. But he had passion, and that's what we all would like to see in our work, I think.And that's what makes him stand out; he was willing to talk about the passion of woodworking rather than the mechanics of it.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in