Boston Bombé Chest

Bulging drawer fronts are all shaped at once

Synopsis: Lance Patterson reviews the history of the bombé chest and then describes how he built one with four shaped drawers, ball-and-claw feet, and a serpentine front. He recommends making full-size drawings first and explains how he showed off the figure in the wood he chose. He talks about how to shape and join the chest and make the bevel dovetails. He spent more money on the hardware than on the lumber, he says, and finished the piece with orange shellac and boiled linseed oil. A side article details how to make slope-sided boxes, such as the drawers in the bombé chest.

More than 50 pieces of American bombé furniture made in the last half of the 18th century still exist. Surprisingly, all were built in or around Boston. The kettle-shaped bombé form (the term is derived from the French word for bulge) is characterized by the swelling of the lower half of the carcase ends and front, with the swell returning to a normalsize base. This shape is, I think, directly related to English pieces such as the Apthorp chest-on-chest, which was imported to Boston before 1758 and is now at that city’s Museum of Fine Arts. Bombé was popular in England for only 10 to 12 years, but remained the vogue in Boston for nearly 60 years.

In America, the carcase ends were always shaped from thick, solid planks of mahogany. In Europe, the ballooning case ends were most often coopered—3-in. to 4-in. pieces of wood were sawn to shape, glued up, contoured and then veneered. Instead of veneering, the Americans worked with solid wood. I think the magnificent grain patterns of this shaped mahogany are a major attribute of Boston furniture. The bombé form, I believe, also shows the enthusiasm that 18th-century cabinetmakers must have felt when wide, dear mahogany first became available to them.

There was also an evolution in the treatment of the case’s inside surfaces and, consequently, in the shape of the drawers. On the earlier pieces, the case ends are not hollowed out and the drawer sides are vertical. Some transition pieces have lipped drawer fronts, the lip following the curve of the case. The fully evolved form has hollowed-out ends and drawers with sides shaped to follow the ends. Some of the later pieces have serpentine drawer fronts.

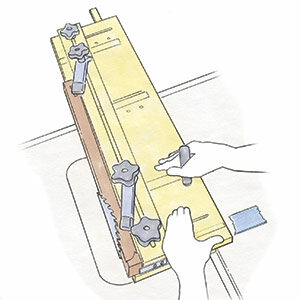

I will describe how I built a small bombé chest with four shaped drawers, ball-and-claw feet and a serpentine front. I didn’t take step-by-step photos while building, so I’ll have to illustrate some operation with photos of Jerry de Rham building his bombé desk at Boston’s North Bennet Street School, where I teach. His version is of the basic bombé form: the front is not serpentine, but bulges to match the ends.

It’s unclear how early cabinetmakers made the shaped drawers, but it probably was done by trial and error, then angle blocks and patterns were made for future reference. There are graphic methods for figuring the angles, and mathematical methods are quick and accurate, too, as explained in the box on p. 57. The same techniques can be applied when designing anything with canted sides and ends, such as a cradle, dough box, or splayed-joint stool or table.

From Fine Woodworking #45

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Bessey K-Body Parallel-Jaw Clamp

Estwing Dead-Blow Mallet

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in