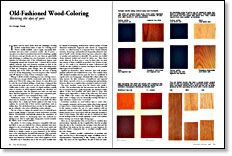

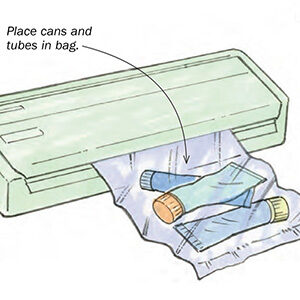

Synopsis: If you’re a hobbyist interested in obtaining a quality of color you can’t get directly out of a can, there are advantages to making your own wood-coloring mixtures by following some of the old-fashioned, bygone ways of preparing natural and chemical dyes. George Frank learned these tips after World War I. He explains differences between paints, stains, and dyes, and talks about the techniques he uses that produce color by chemical reaction with the wood itself. He talks about using logwood and brazilwood powders to make dye, explains what mordants are and how to use them, and describes the tools you’ll need and precautions to take. Photographs show how these dyes affect different types of wood. Side information offers a unique story about dyeing pine — while it’s still growing.

There can’t be much doubt about the advantages of using modern ready-mixed stains or dyes for coloring wood. They’re readily available, easy to apply, reasonably faderesistant and they yield consistent results. But if you’re a one-piece-at-a-time wood artisan interested in obtaining a quality of color you can’t get directly out of a can, there are great thrills and advantages to making your own homemade wood-coloring mixtures by following some of the old-fashioned, bygone ways of preparing natural and chemical dyes. I learned about various natural extractive dyes and chemical mordants in Paris in the days following World War I. Although the old woodworking section of Paris has undergone many changes since the unforgettably charming days of the 1920s, and while the old ways of dyeing wood are slowly disappearing, I haven’t forgotten what I learned and still depend on many of these techniques today.

Why go to all the trouble of making your own coloring concoctions when you can get reliable, ready-made stains at the corner paint store? First of all, using a dye instead of a stain allows you to color the wood without adding a cloudy layer of pigment that can conceal the grain and cover up the wood’s natural beauty. Unlike paint or stain, a dye consists of a liquid medium—usually water or alcohol—in which pigment particles are dissolved, not merely suspended. Thus, the pigment can’t settle out. And since these dissolved pigments are less opaque than suspended particles, a dye solution is more transparent than a stain.

Furthermore, many of the techniques I’ll describe produce their color by chemical reaction with the wood itself. The effect they achieve has a clarity and vibrant quality of color that, in my opinion, far exceeds that of their modern equivalents, such as aniline dyes. The old-fashioned dyes can also be the right way to get an authentic color when refinishing certain antiques.

The use of dyes to change the natural color of a material goes back to textile dyeing—a craft that evolved well before recorded history. Woodworkers undoubtedly gleaned the experience of these textile artisans in developing their own methods for dyeing wood, often to make light, inexpensive woods resemble the darker, more coveted varieties.

The palette of color-creating substances compatible with yarn and fabric is vast, yet relatively few of these materials have been adapted to the wood-dyeing craft. One of the most useful and well-known of these dyestuffs is brewed from the hulls of walnut shells by so simple a means as a pot simmered on the kitchen stove or by extracting the dyestuff with ammonia. This venerable brou de noix, which Jon Arno wrote about in FWW #59, produces very handsome rich-brown colors when applied to wood.

From Fine Woodworking #66

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Starrett 12-in. combination square

Double Sided Tape

Osmo Polyx-Oil

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in