Please HELP me (Box Joint Making)

Hello, all! I am new to the community and fairly new to woodworking, I’ve been doing it for a couple of years now however I’ve only ever utilized butt joints, lap joints, and pocket holes for any of my joinery in the past.

I am trying to step my game up by creating more illustrious, stronger joints beginning with box joints. So I’ll jump right in to my complications: I have a 24″x24″shop-made router table. I have a makita RT0701C Palm router mounted underneath the table. And I am using pine ‘Premium Select’ from home depot (not sure how but it seems they make these boards much harder than traditional common boards).

I have created a box joint ‘sled’ type jig that glides squarely across my route table, and feeds work pieces into the bit to create box joints. Although I have had some success, as none of my issues lie in squared-ness, distance gaps, or any of the other common issues.

However!! I continually get large chunk blowouts and tearouts not only on my joints, but when attempting to create a new jig template for different sized bits – mostly when I go to make the second mortise (or slot) and it tears out the tenon (tooth piece) [disclaimer : I only use parentheses because I’m not 100% sure I’m using these terms correctly] and leaves me with one large utterly useless slot either in my workpiece or in the template I am attempting to make for another joint size.

I have tried tampering with lower and higher speed settings on the router, I have run the grain of my pieces both parallel and perpendicular to the router bit.. Is it because I’m using pine and it is too soft a wood to withstand a full box joint cutout in one shot? Could it be that my router cannot keep up with feeding a full 3/4″ cutout into it at one time, and I need a larger router?

I really don’t know what else to do, please help me understand how I can correct this issue. Thank you in advance!

Replies

When you push stock through the router bit one side of the exit wound is being cut as intended and one is being cut on a climb.

The edge being climb cut will be prone to blowout with a straight bit because it it being "slapped away" by the cutting edge rather than "bitten into" like on the other side of the exit cut. Backing up the cut with a zero clearance sacrificial carrier can help.

An upcut spiral (which will downcut into your router table) can also help because the cutting action is a shearing cut rather than a "slamming" cut as with a normal straight bit and is less likely to blow out the exit face.

Thank you so much for your response here, MJ! This actually describes exactly what is transpiring here. I am feeding my stock in to the bit and the direction in which my previous 'slot' was cut becomes totally or fully blown out even mid-way thru the making of the second slot.

Ironically as I am seeing your response here I am literally looking on Amazon for spiral bits to see if they will help! 😂 my thought as well is maybe my straight cutting bits are too 'blunt'.

Although this may be a solution and I will be trying a spiral bit instead - I see many videos of others using straight cutting bits for this very same purpose, creating their finger joint slots with seemingly no issue whatsoever on a straight bit?? I don't understand why I am unable to obtain the same result, other than attributing it to either the fact I'm not using hard wood stock and therefore cannot withstand the more brutish force from a straight cutting bit, or otherwise the fact that my router is only a small palm router and when applying 3/4" of stock to the bit, the router is unable to maintain it's rpm and becomes more of a hammering motion than a slicing motion, for lack of a better description.

I appreciate your input and am open to any and all tips on this topic, as I believe I have done my diligence in research yet still am unable to achieve satisfactory results. I am on my own here as I learn via trial and error throughout my woodworking career; I have never had a mentor or anyone to personally refer to for these issues.

MJ

In the interest of providing accurate information for a new woodworker. Your information regarding the cause of the tear out is likely correct, but inverted. Climb cutting is when you feed with the direction of rotation and the cutting edge leads into the wood, this actually gives a cleaner cut less likely to tearout it is the other edge that is causing the tearout. The problem with climb cutting is it can make a router difficult to control so should be used with caution. As you correctly stated cutting box joints entails both types of cuts its just the non climb cutting edge that is causing the problem.

I agree with everything MJ had to say and would like to offer another solution. Try precutting the fingers and using the router essentially just for stock removal. you can precut with a hand saw or on the bandsaw. I like a Japanese Dozuki saw for this, but a dovetail saw will work just as well.

That is a great suggestion and I will be giving this a try tomorrow, I don't have a band saw or any specialized handsaws - however I do have a small scroll saw that should be able to accomplish this!

I just re-read your OP. If you are running a 3/4" bit to take a 3/4" deep single pass cut with a 1/4" collet trim router you are definitely over-reaching the capabilities of your equipment.

Everything I said earlier still applies, but your odds go WAY up with a real router with a 1/2" collet and bit.

Understood and agreed, however no I apologize if I mis-spoke; I am running only 1/4" ' 1/2" MAX diameter bits, at a 3/4" depth in one pass. It was rather successful in the beginning with the 1/4" bit I've managed to create a near perfect finger joint at first and was thrilled about it, but since then trying to create a 3/8" joint after creating the 3/8" template has failed, and then attempted to create a 1/2" template also failed.

I figured in part my router would limit me in this process, however I intended to at least be able to reliably create 1/4",3/8", and 1/2" finger joints with my current set up.

Ultimately I will eventually be upgrading my router when more financially capable to. I guess I just needed to be reassured that it was necessary 😁

However I also just wanted to reach out and hear what other more experienced craftspeople do about this, if anyone else uses a smaller router to create joins, and if it is even feasible to expect such performance from rather softwoods like pine - or if I should basically expect poor (or unpredictable) results so long as I work with pine woods bought from department stores, despite any and all technique or precision.

It seems as if most wood crafters hardly work with cheaper woods like pine from what I am able to gather via the internet, and are always working with hardwoods. My experience in working with anything outside of store-bought pine boards limits me in knowing what results to expect in comparison to sturdier wood species also.

It seems as if my replies aren't posting, or I cannot see them?

Edit : now this one seems to have appeared finally!

Thank you for your responses they are very much appreciated and helpful!

MJ, I could not have said it better myself in how you describe what is transpiring. The bit seems to bat out the material left between my initial slot and the subsequent slot as soon as the bit even begins to make contact with the workpiece (or template I am attempting to make for another bit size)

To be clear, and I apologize if I mis-spoke originally - I am attempting to cut 3/4" depth slots, but only with 1/4",3/8", and 1/2" bits MAX - not 3/4" depth cut with a 3/4" bit in a single pass.

Although I expected to be limited with my current router in this capacity, and with any other routing application I have always done my cuts in 1/4" increments as a rule; I figured I might be expecting a bit much of my small router to neatly take on 3/4" depths with any size bit.

However, none of the articles or videos I've seen gave any information on what the optimum router size would be for creating finger joints in singular-passes, nor did they describe which type of wood would be best or most structurally-reliable to avoid tear-out and breakage (or more particularly, if pine boards are strong enough to withstand this application). So I was unsure how much of these complications could be a result of those factors - and basically if this was something material/tool related, or technique/setup related on my part.

I have been essentially learning on my own, so my experience is limited by what I have access to - which is a small router and cheaper/softer wood stock 😂 and all I've seen are videos of people using a shop-made box joint jig effortlessly making flawless joints effortlessly, yet this rather simple task has been almost nothing but frustrating for me with persistent blow outs and tears (other than the very first joint I made with this jig)

I will be trying any and all suggestions given here, and your experience is greatly appreciated - as like I said, I have no one else to refer to with such problems and tend to spend weeks in trial-and-error.

Beok21

I will say your problems are caused by more than one thing, read my reply to MJ's original post regarding climb cutting, the pine is also a problem since it is weaker than most hardwoods and thus more prone to tearout, so do reduce this tearout you need to reduce the force being applied. You can accomplish this by reducing the depth of each pass and running the router at its maximum speed, this will let the router take smaller chips and reduce the likelihood of tearout. I would start with a 3/8" depth of cut and go to 1/4" if tearout is still present. If you are trying to cut wider box joints, larger than 3/8" I would suggest using a smaller bit first then using the the final diameter bit in a single pass to clean out the joint. Your trim router would be greatly stressed by cutting over 3/8" in my opinion.

Regarding the pine you're buying at Home Depot. You are paying more than you need to for your low quality wood. Invest in a bench top planer as soon as possible and start buying hardwoods in the rough. You are paying almost $6 a board foot for low grade pine in my area I can buy cherry for $5.25, red oak for $3.45, poplar for about $2.25 b.f.

With bench top planers starting around $400 they can pay for themselves fairly quickly.

Even if you don't most hardwood dealers will plane wood for you for a small additional charge and you still will pay less than the big box stores.

As others have mentioned, there are a lot of factors involved in your issue. The solution is to deal with those most affecting the tear-out and splintering.

The router needs to be spinning the bit without wobble and the bit needs to be gripped firmly enough to not deflect unduly when applied to the work. Your shop-made router table and sled, along with a small router, may have various "slops" that are adding to the problem, even though these "slops" might be very small. There's a lot of forces involved when you cut in this way so any weakness in your apparatus will be immediately found out when cutting.

When you push the workpiece through the bit, that workpiece also needs to be held very firmly in place, so it can't tip, move side-to-side or twist, even by very small amounts. Any incorrect movement of the workpiece can allow the high cutting forces to go where they shouldn't.

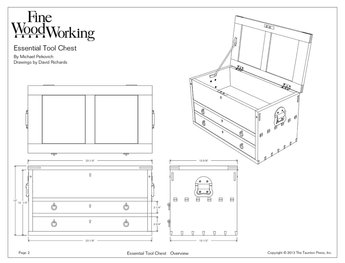

Two pics are attached showing the finger joint arrangement on a Veritas router table with a cross-cut sled, set up for finger jointing. The Veritas arrangement is instructive for any such finger joint cutting arrangement.

* The sliding cross-cut fence moves smoothly with absolutely no side-to-side or up & down wobble.

* The metal fingers fit tightly into the last-cut finger gap so no side-to-side wobble of the workpiece itself can occur.

The backing block is end grain (so less likely to itself splinter when cut) with the workpiece tightly held against it (no back & forward wobble, no gap).

For smaller fingers, the workpiece can be hand-held against the fence; large fingers are best made with the workpiece clamped to the fence.

The router table top must be flat so the workpiece always moves in the same horizontal plane with reference to the bit height.

The router needs to be very securely mounted to the router table top, which itself must be secure on it's stand or whatever holds it in place.

The router, the collet and the bit need to be beefy enough to prevent any bit wobble, flex or runout. A spiral-edged bit can help smooth the cutting action, as the workpiece is cut continuously rather than every 180 degree turns of the bit.

*********

Even with all the above factors met, you must pass the workpiece slowly over the bit - don't hurry. Make sure the workpiece is always tight against the backing fence and anti-breakout backing block, as well as firmly and correctly positioned on to the fence locating finger and down on the router table top. It takes a lot of continuous concentration to ensure everything is set right for every single cut.

When the bit is cutting both sides of the workpiece to make a finger gap, the climb cut forces should be equalised and eliminated by the cutting forces on the other side of the bit. any snatch will be due to wobble or poor grip of the workpiece as it's cut.

But the last cut of just one side of the workpiece, at it's end, can be a snatcher because only the climb cut is then being made. This is where a clamp and a very careful and firm control of the sliding fence is most important.

*****

Any timber can be cut in this way if the feed speed is kept low, the whole thing is tightly held and the bit spins fast with no wobble or flex.

One final thing is to have dust & chip extraction always on, as the chips can get into the various interfaces between the workpiece and fence or between the fence and the router table top. This too can cause those raggedy finger joints, as it spoils the correct positioning of the workpiece. Blow any dust and chips remaining off the router table top after each cut.

If all the above is performed, there should be no breakout. I've cut thousands of fingers like this, from teeny 1/8" X 1/4" deep to 1/2" X 1" deep, in many kinds of timber from splintery low-density sapele to dense and swirly-grained teak.

See that grandson cutting perfect fingers first time!

Lataxe

In the below referenced episode from The Wood Smith Shop they made a special jig for cutting box joints. They used a trim router to make them. I have not tried this item but only provide it for you inspection.

https://www.woodsmithshop.com/episodes/season12/1207/

@esch5995; thanks for the correction on the "climb" definition... I should have just stuck with "slap cutting". :-)

UPDATE: Plans below for box jig.

file:///home/chronos/u-03cf9c97a75e86de923f290deb4f175a16cc50c8/MyFiles/Downloads/SN12416_finger-joint-jig%20(1).pdf

Thank you all beyond expression for your time in explaining everything that you have, just when I felt like I thought of everything.. Apparently far be it from me 😁

This was all hugely informative and honestly applicable on many levels even outside of my router's failing finger joint sled.

Although I have spent a good amount of time on my router table as well as my jig, I'm certain they aren't perfect and I'll be re-engineering a few things that come to mind where play/slop could exist.

As I suspected there is much for me to learn, and thanks to you guys I now have a good few directions to steer myself toward.

There is MUCH for me to chew on and try to work out here. After reading everything here I feel that I've gotten my builds 90% right, even in an attempt for them to be 100%, but that remainder 10% of meticulous detail may be where I find my resolve.

On another note, this is my very first time joining a forum or even asking a question online and you all have been superb and very welcoming in your responses, just wanted to emphasize this again as it truly is helpful and your time is appreciated.

I will post an update after I make some changes based on what's been said and shared here to see what you all think very soon!

This forum post is now archived. Commenting has been disabled