Protecting Less-Known Tree From Disease

November 28, 2006

Protecting a Little-Known Tree From an Insidious Disease

By MURRAY CARPENTER

JERICHO, Vt. — In the 29 years since a fungal disease known as butternut canker was first observed in southwest Wisconsin, it has infected over 90 percent of butternut trees throughout their native range from New Brunswick, Canada, to Georgia to Minnesota.

Dale Bergdahl, recently retired after 29 years as a University of Vermont forestry professor, has been tracking more than 100 butternut trees here in the University of Vermont’s Jericho Research Forest.

Dr. Bergdahl was the first to find the canker in Vermont, near Snake Mountain, in the fall of 1983. Since then, it has killed half the butternuts in the state. The fungus, Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum, was described as a new species in 1979 and bears the earmarks of being recently introduced. But it has never been found outside North America.

Dutch elm disease and chestnut blight, also caused by fungi, were notorious, and much more conspicuous, because elms and chestnuts were abundant. Butternuts are little-known, however, and have always been sparsely distributed. But there is a growing effort to understand the disease. In mid-October, Dr. Bergdahl was among 40 scientists and foresters from the United States and Canada who met in Niagara Falls, Ontario, for the Butternut Canker Research Symposium.

Though many people have never heard of the butternut, the tree has a long and history of usefulness. Indians tapped it for syrup, used the bark for medicine and dye, and ate the hard-to-crack but tasty nuts raw or boiled them to produce a buttery vegetable oil. The Vikings of L’Anse aux Meadows gathered butternuts from points south and took them back to Newfoundland. Confederate soldiers used the husks to die their uniforms a golden brown (earning them the nickname butternuts). The rot-resistant wood, often called white walnut, is favored by some woodworkers. Butternuts are also important to wildlife: many mammals eat the nuts.

The tree is closely related to the black walnut, and their ranges overlap, but walnuts range farther south and butternuts farther north. Like walnuts, butternuts are intolerant of shade and their roots exude a poison known as juglone to kill competing trees.

In an effort to track the spread of the disease, Dr. Bergdahl and colleagues established 18 permanent research plots in northwest Vermont from 1993 to 1996. They measured, tagged and assessed the health of 1,269 butternuts and logged the Global Positioning System coordinates. In 1996, they found that 92 percent of the trees were infected with the fungus, and 12 percent had been killed by it. By 2002, the infection level had increased to 96 percent, and 41 percent of the trees were dead.

In 2003 and 2004, Dr. Bergdahl and his associates established 24 additional plots and evaluated another 1,054 butternuts throughout Vermont. Every butternut they assessed was infected with the fungus, and half were dead. There was virtually no regeneration among the butternut stands, and the few young trees they found had been infected already.

The spores of the fungus are spread by rain splash and wind, but the rapid spread of the disease suggests that insects also act as vectors. Dr. Bergdahl and his colleagues have found that at least 17 species of beetles closely associated with butternut can carry the spores. A single beetle can carry as many as 1.6 million spores (just one is needed to cause an infection), and the spores can remain viable on insects for at least 16 days. The fungus can also be carried on the nut; some trees are infected before they even begin to grow. The incidence of fungus-killed butternuts in Vermont is increasing, and Dr. Bergdahl projects that 85 percent of the butternuts in Vermont will be dead by 2011.

Dr. Bergdahl said the fungus is just one of many influences that are changing the composition of the Eastern forests. The hemlock wooly adelgid, the pine-shoot beetle and the emerald ash borer are among the introduced insects that are killing trees now, and the Asian long-horned beetle is approaching. The fungus that causes sudden oak death in California and Oregon is another potential threat. Dr. Bergdahl said this wave of invaders is a result of worldwide trade in which “commodities are moved in huge quantities very quickly.”

There is no known treatment for the butternut fungus, so conservation efforts are focused on finding and protecting resistant trees. The question is whether the few trees that appear resistant are genetically pure. Butternuts can hybridize with other trees like the Japanese walnut, which was introduced to North America in the 1800s.

Some protective measures are in place. Minnesota has had a moratorium on the harvest of healthy butternut trees from state-owned land since 1992. The Forest Service considers butternut a “sensitive” species on its lands in the Northeastern United States and has begun a program in Wisconsin to preserve disease-free selections by grafting butternut scion onto black walnut roots to produce seeds for restoration projects. Butternuts are listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, and Tannis Beardmore, a researcher with the Canadian Forest Service, is keeping fungus-free butternut seeds in frozen storage in Fredericton, New Brunswick.

Dr. Bergdahl said there was no advocacy organization similar to the American Chestnut Foundation focusing on protecting butternuts, but he said he was interested in starting one. For butternut lovers who simply want to give the trees a boost, he suggests planting nuts in open areas, covered by a screen to keep squirrels away.

While the October symposium was an important first step for scientists sharing research, most people still know nothing about the disease, Dr. Bergdahl said, adding, “The general public won’t understand it until the trees start dying all around them.”

Home

* World

* U.S.

* N.Y. / Region

* Business

* Technology

* Science

* Health

* Sports

* Opinion

* Arts

* Style

* Travel

* Job Market

* Real Estate

* Automobiles

* Back to Top

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company

Replies

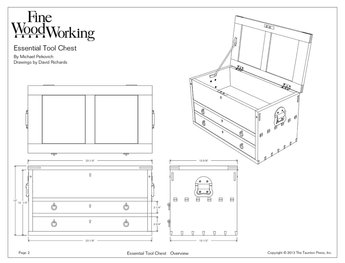

Sad, a great wood to work with, a little fibrous but very easy on tools. Made a hope chest out of it when in college, all by hand, beautiful...the ex-lady friend has it now.

Donkey

This forum post is now archived. Commenting has been disabled