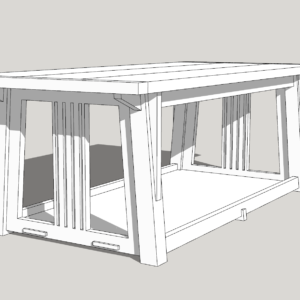

This is my first piece that I have designed and it will be a gift for my parents. Its inspiration was drawn from a Ginko Leaf end table I saw. I am interested in any feedback and thoughts, especially if there are any areas of concern that I should address. The construction will be a combination of mortise and tenon, floating tenon, and bridle joints. The top will be a breadboard panel secured with buttons. I am going to try and do the bulk of the joinery by hand. As far as wood selection goes I am leaning towards cedar for the bottom shelf and a waterhog mat, this is for boots after all. For the rest I am thinking about using Beech or Ash for durability.

Thanks in advance,

Brandon

Replies

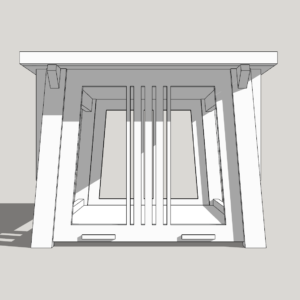

First question that pops into my head is how do you I tend to attach those slats in the center of the ends? Without dimensions it's hard to be sure, but they appear to be narrow yet the same thickness as the top and bottom rails which I assume are mitered to the stiles, but your model shows no visible joinery lines. Mortise and tenon joints here might be possible, but if the outer slats are as thin as they seem, would be somewhat delicate. My guess is 3/16" x ¼" if the slat is ½" x ¾" although strength is not an issue, I'm not sure I would want to cut such a joint.

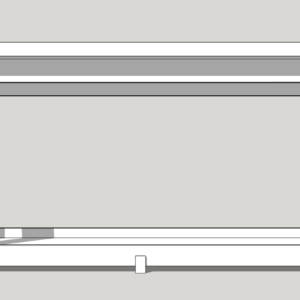

Thanks for getting back to me so quickly. Good call out on the dimensions, the inner measurements of the base are 46" x 18". The overall height of the bench will be 18" as well. That side face is 3/4" thick and the 3 center slats are 5/8" wide while the outer slats, and the 4 dividers, are 5/16". The bottom has a 1/2" slot for the bottom shelf with full thickness through tenons. The legs are 1 3/4" x 1 13/16".

My thought for those side plates is that I would try and mill them from a single piece assuming I could find a slab large enough.

Ive uploaded a view of the side component isolated in sketchup and from the inside. I also added a closer view from the front that may give a better sense of the proportions.

Cheers

Can I ask your experience level? You mentioned doing much of it by hand, does that mean true hand tools or are you thinking of using a router to mill the ends? I would not count on finding a slab 18+" wide to mill the sides from so count on gluing it up or devise another method of construction.

Also consider making the bench out of something like White Oak which is more than durable enough to withstand some water from boots, assuming a good polyurethane finish, or was the cedar a design choice for some other reason?

Even if you could do those ends with a single board (unlikely to be found), I think grain orientation on the parts that run side to side would weaken it.

I'd consider my skill level intermediate. But yes, I plan to use hand tools for most of the joinery; router plane, chisel, hand saws etc. I certainly can entertain using my bench router though, especially if I swap out the floating tenon for a sliding dovetail.

The cedar was purely for moisture resistance, if white oak can hold up I'm open to looking into it.

Regarding the side panel and the legs it should all be long grain to long grain so I'm hoping strength won't be an issue. I could swap out the tongue and groove joint for a floating dovetail if I needed to. Given the general wedge shape, and the aprons going through bridle joints in the legs I think I think it should be ok.

I'd not use cedar just because it is too light (you want your weight in the base) and it's a bit soft for boots.

Most timber will survive a bit of damp provided it is sealed - polyurethane is king there. There are a LOT of oak framed buildings in the UK which have stood up since around the time Colombus sailed to the Americas...

If you are anticipating a lot of moisture then you may want to think about ways to keep it out of any joinery, but I'm guessing this is an indoor piece.

As I understand it, American white oak is not as durable as European oaks - although still resistant to rots and beetle to a goodly degree. But if it's protected with a waterproof finish, that will be moot.

********

The skinny slats central to the ends of the structure could be attached to the upper and lower rails with dowels. Dowel centres (small metal roundels that fit in a dowel hole with a point sticking out to mark the matching dowel hole location) will enable alignment of the slats with the top and bottom rails, as well as the spacing.

Alternatively, through dowels could be drilled from the top and bottom of the upper and lower rails respectively, into the ends of the slats, temporarily held in place with clamps across top & bottom rails. The rail edges with the exposed dowel ends would be hidden in the finished piece.

The slats are small; but dowels can be got as small as 3mm / 1/8" diameter. Such a dowel joint wouldn't be a strong joint - but it doesn't need to be, really, in that location within the piece. Gluing of the end grain of the skinny slats to the long grain of the rails, although weak, would help keep the slats from rotating on their dowels.

Another alternative is to make square stub tenons on the slat ends to go into matching stub mortises along the rails. That would need very neat joinery but I have done such a thing. A mortising machine square chisel bit without the bit can make accurate and small square holes for chiselling out if one is careful. Stub tenons can be made with a Zona saw or on the TS (if you have a sliding carriage and a fine finish blade).

You can also make the rails of three thin slices, with the middle slice given spaces for the stub tenons before the three slices are glued up into a rail.

Lataxe

I think you will find the first alteration to your plan will need to be, the idea of making those side pieces from a single wide board. The first consideration is the likely hood of finding such a wide slab, possible (especially in White Oak) in an exceptional hardwood dealer but far from common and expensive. That leaves gluing up 2-3 boards as the best way to meet that particular goal. As for a concern about the short grain that would be present at the inside corners, given that the load is carried by the vertical portion of the sides I don't see that as an issue. It is the idea of cutting those slats and even the larger openings with hand tools that just seems impractical to me. I can't even think of a practical way to do it, saws would leave a very rough and uneven edge surface that would need to be smoothed, but with what? Files and sandpaper sticks? How long would that take? Of course a portable router would be the tool of choice if you are willing to abandon the plan to use purely hand tools, which seems to be in play. Then you could simply square the corners with some chisel work.

The other alternative is to abandon the idea of using a single slab on the sides and use some type of frame construction, either mitered corners or rail and stile with mortise and tenon joints. This raises the question of how do you attach those center slats? There is no easy solution to attach a slat that is 5/16" x 3/4". I know no way to suggest how to attach a slat that is 5/16" x 3/4" with any mortise or dowel, maybe you could only cut 2 shoulders leaving a tenon 5/16" square, but the precision of your mortise would need to be exceptional. The slightest of miscuts would be visible, especially at the bottom joints. In addition a tiny deviation from square would leave the slats skewed in relation to the rails. This could be solved by starting with slats that would be slightly thicker that 3/4" then planing and scraping them flush after assembly.

A third possible construction method would be to plan on doing a glued up panel of 3 boards but have the center board be the slat assembly. In other words cut 2 boards into "C" shaped pieces any way you planned, smoothing the inside edge before assembly. Then "build" the center panel from a series of glued up slats, some cut short and installed top and bottom to create the gaps between the long slats. If care was taken to keep the slats in sequence as they are cut, and thin kerf blades are used, the disruption to the grain pattern would be hard to notice. Quartersawn wood could be a benefit here. This assembly could then be glued between the two "C" shaped sections and you would have your desired results. This eliminates the difficulty of finding a single board in excess of 18" wide and brings the scope of the project within the realm of being practical for hand tools.

I wish you luck with this project. It certainly is a good example of how something that seems simple during the design stage can really test you during construction.

PS. I would consider using quartersawn white oak for this project for a number of reasons, not the least of which is its Arts and Craft style look in which quartersawn white oak was probably the most commonly used wood.

This forum post is now archived. Commenting has been disabled