Learn From Antiques

Avoid construction mishaps by looking at mistakes from the past

Synopsis: If you want to build furniture that will last well into the future, the best place to look is the past. Period furniture expert Steve Latta scoured the countryside in search of antiques, looking for cracked tabletops, split sides, broken bracket feet, loose moldings, and other flaws that developed over time. Then he provided solutions that will prevent these problems from happening to you. Most often, the culprit is wood movement and the solutions are simple.

Let’s say a future woodworker examines my furniture 100 years from now and notices a few consistent failures. Now imagine that person visits me in a time machine to tell me where I went wrong. Well, you can bet I would listen to him or her and make some changes to the way I build.

Luckily for us, we already have a time machine, thousands of them, in fact. Antiques let us see what happens to a piece during its life, and I’ve learned much of what I know by closely examining many of these old pieces.

For this article I scoured a number of my favorite furniture barns and museums, looking not only for cracks and breaks, but also for the most instructive failures—common problems that happen in pieces of all types and styles. I found the perfect collection at Philip H. Bradley Co., an antiques dealer in Downingtown, Pa. Bradley’s pieces are iconic and beautifully preserved, and plentiful enough to contain many of the usual issues I’ve encountered in my decades of furniture study.

Wood movement is the creator of headaches: In most cases of furniture failure, the problem is the same: The maker did not sufficiently accommodate the seasonal shrinkage and expansion of wood parts. In a nutshell, wood barely moves along its length but moves a great deal across its width, and can do so with great force. When that movement is restricted, bad things often occur.

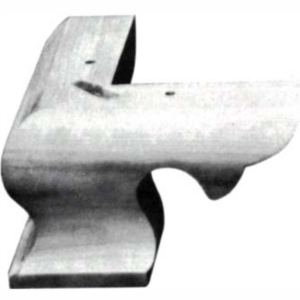

The most common type of restriction is cross-grain construction, where two or more pieces are joined together at opposing angles. One piece wants to expand and contract across its width, while the other piece doesn’t move at all along its length. Soon cracks and splits make their debut. If a piece is veneered across the grain of solid wood below, you get buckles and bubbles.

To fix or not to fix: In each case of furniture failures that follow, we’ve provided an illustration of why the problem happened and how a modern maker could prevent it in their own work. However, for a reproduction woodworker the solutions are not always clear-cut. How far a builder strays from the original is a matter of compromise and choice. Some argue that we should build exactly like our forefathers did. But for me, “because they did it that way” has never been a very strong argument.

One shop in my region was determined to build veneered card tables the exact same way the originals were built. They did not cross-band the bricklaid cores, and they considered the inevitable split veneers to be part of the “charm” of working with solid wood. When I made a table that way for a friend years ago and the face veneer split, neither he nor I found the crack charming. After that, I made sure to cross-band my cores.

While I tend to stay conservative in my approach, I always give top priority to the future integrity of the piece.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Estwing Dead-Blow Mallet

Festool DF 500 Q-Set Domino Joiner

Circle Guide

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in