Loading large logs require heavy equipment

Advanced Veneering and Alternative Techniques

elevate your woodworking to a new level with the use of veneer

(Part Two: Will Your Tree Make The Cut?)

It seems like every year I get a call from a friend telling me about a tree that just fell in their front yard, or that needs to come down, and asking if I would be interested in it. They want to know the value, too, often thinking they just hit pay dirt.Like most things, there are two sides to this story.

My first answer is usually no.

It takes a lot of time and effort to cut, move, and clean up a site, let alone store, mill, and dry the wood. Even if it is a high value tree such as black walnut, there’s not much I can do if a mill won’t cut it. There’s a good chance that these “yard trees,” as they are referred to, can contain nails and other hardware which will wreak havoc on saw mill blades. Often, mills will refuse to cut the first ten feet of the tree, which has the best lumber, and is most likely to contain metal. Sometimes they’ll use a metal detector, but that doesn’t always work, especially if the tree is particularly old and large diameter. The fact of the matter is, the majority of yard trees are not very valuable in terms of lumber, so tree owners beware.

Nostalgic value is another thing altogether.

Pieces created using lumber from these sentimental trees has an intrinsic value, and the furniture created will become more than something functional. Owning a piece of furniture that is made from a yard tree, perhaps one that was planted by one’s great grandfather, or the tree that one’s children played in, can have great value. It will have a soul with a wonderful story and become a valued family heirloom. The extra effort is well worth preserving the history within the piece, so woodworkers beware.

There are a lot of issues to be considered, starting with making the right first cuts. You need to determine how much lumber the tree will yield (probably not as much as you think); what types of cuts should be made (plain sliced, quartered or crotches); live edge or sap / heart wood, what lengths and where to exactly place the chainsaw.For example: if you want crotch material, it means you’ll cut 24-inches back from each branch “Y”.

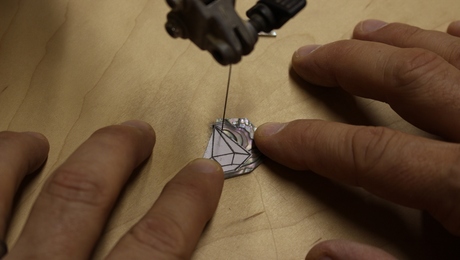

Simply moving and transporting the logs can be a logistics challenge, too. Milling onsite with a portable band saw mill or chainsaw setup is a viable option but is more expensive than delivering to a mill. Chainsaw systems are great for extra large-diameter logs and often the only option, but they are slow, they waste material, and they are not as accurate as a band saw mill

Next, you have to properly dry the lumber either by air or kiln, which takes knowledge and patience to avoid unnecessary checking, warping, bug infestation (not all woods need to be treated with insecticide), and material waste. In either method, you will need to know what you will be using the lumber for: construction or furniture, and the type: indoor or outdoor, each requiring different moisture contents.Time of year the lumber is cut, milled, stacked, in addition to thickness, species, local humidity and temperature all effect air drying times.For estimated air drying times of a variety of hardwood species in different areas across the United States, you can visit the USDA Forest Products Lab.

The boards need to be properly stickered (stacked boards separated with sticks for ventilation during drying), and the stack protected from the weather with plenty of air movement. I like to tightly strap bundles with metal banding to help contain them.

Kiln-drying a single tree can be a challenge as driers do not like to deal with small quantities, various thicknesses, and different lengths. Other considerations are moving, sorting, storage, grading, selling extra material, and more handling.

You also have to remember that it is important to seal all end grain immediately after cutting any green wood, and with burls, you seal the entire piece. (Note: to preserve bark on a live edge, it is best to fell the tree in the winter months.)Once a burl is roughed in within one inch of the final thickness, I treat the green lumber in PEG (Poly Ethylene Glycol) which displaces the water within the wood cells, stabilizes the lumber, and helps prevent checking.

So before you consider turning your yard tree into a piece of furniture, be sure you know what you’re in for.

Check out Part Two: Does Your Tree Make the Cut?, and see what happened to me when I said yes.

Comments

A thorough, well written article. I milled a walnut tree myself with a chainsaw rig 14 years ago and stickered them in a metal shed. Last year, I pulled out the material to use for a project, only to discover that the 6" material was still sopping wet inside(>22% moisture content), so the old rule of a year per inch of thickness does not apply over about 3" thick. For a client with a sentimental tree, I found a local band mill with a small kiln who was willing to dry 600 feet of white oak for me, but I had to wait until he had space in his kiln. Depending on the species, I discovered, drying schedules can test a client's patience. My local tree trimmer assessed my walnut trees value, a function of both diameter and height to the first branch. Most wood turners prefer to turn bowls green, and are often interested in sections that might otherwise go to waste such as the stump. Teaming up with a turner in processing a tree can lighten the work.

I Have 3 big Elm trees due to come down this year. Now I wonder if its even worth it to try and get them milled. Hurry up and post part 2!!!! I can't wait.

Excellent article I learned some things I didn't know.

BKG

In my area, Northern VT, a portable mill is much less expensive than trucking and milling off site. You provide more of the labor in the process, further reducing expenses. When we suspect hardware, my sawyer will install a blade nearing the end of it's usable life. If that blade is damaged, I'm charged accordingly.

I'd underscore two points:

Agreeing to take "free wood" whether a standing or downed tree--or even milled lumber--requires experience and an up close & personal look. When I was running a woodworking program for my school district I was offered free materials many times--milled lumber as well as standing and fallen trees. Callers were often taken aback at first when I never agreed to take anything sight un-seen. Most offers turned out to be trash material. I only got really lucky twice in 16 years. Those two finds--20 boxes, each containing one thousand 1/4" dowels, 12" long and the other a 10' x10' garden shed full of custom moldings--gave several district woodworking teachers some fine free supplies..for several years.

The other circumstance when it may be worth your time, the expense and the very heavy labor to salvage yard trees is the prospect of using heirloom wood. Very small pieces of material from a small tree--or even a large shrub--can be turned into genuinely priceless objects. My daughter's kindergarten class had a hand in planting a fruitless mulberry in 1978. Only twenty years later-- and entirely coincidentally--a friend teaching at the same school told me a tree was being removed and could I use some free wood for my classes. When I asked which tree and learned it to be the one my daughter's class planted I got enough material to turn three large bowls from it--one for her, one for her mother and one for myself. I did the same for an elderly friend who offered me a downed tree for firewood. His Grandfather had planted it over a hundred years before. For him 3 bowls were an unrequested surprise. That's all I could salvage from the 10' x 16" log so I did split and burned the rest of it.

If you want to try salvage logging start small.

Having grown up in OK and TX where scrubby mesquite are the dominant trees, I couldn't stand the thought of just burning the oak, maple, cherry, and locust trees on our Maryland property that needed to come down. Fortunately we were in rural area and I found a bandsawer and a really great yard guy with a small dump truck and a big Bobcat. I cut the wood into 6/4 and because I had a large lot, I was able to air dry the wood for three years. The locust is now two heaviest Adirondack chairs and a settee. The cherry and oak have made several boxes for military burial flags. I also scored an large old walnut tree which started growing south of DC around 1830 and air dried it. I also have some small branches from a pecan planted in the late 1700's.

When we moved to Illinois (don't ask!) I couldn't bear to leave the wood, so me, a buddy, a U-Haul truck took a 1000 mile road trip. A garage is now full of air dried but badly stickered lumber which I am now able to tap for all manner of projects.

Scott's article is spot on in identifying the many reasons to say no. And he is particularly eloquent speaking about the nostalgic value of turning a historic/beloved tree into a beautiful piece. Given all the various invasive hardwood diseases (Emerald ash borer, walnut thousand cancers disease, sudden oak death, etc.) I just can't see simply burning or shredding a tree if it can be salvaged with reasonable effort.

Charlie Pitts

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in