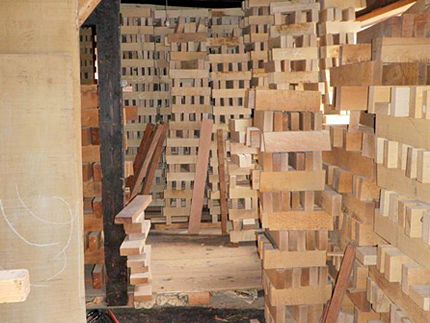

The workshop of dai (plane body) maker Isao Inmoto.

By Garrett Hack

Part two on Garrett Hack’s recent trip to Japan. In part one, read about Hack’s visit with a Master Craftsman and his particpation in a “plane off.”

To the northwest of Tokyo, all the way across Japan, is the tool making center of Sanjo City. I had introductions to two craftsmen there, a maker of wooden plane bodies (dai) and a father and son pair of blacksmiths making all types of edge tools.

Communicating with them was going to be a problem, as few of the craftsmen I met spoke much English. Fortunately, by the time my class ended near Tokyo, I had 4 woodworkers who wanted to tag along, all willing to translate.

The Dai (plane body) Maker

Isao Inomoto works in a modest shop in a line of what look like small factories. Trained by his father, Inomoto-san has been making dais for all of his 70 years. He is considered one of the best dai-makers in Japan, where craftsmen with the most revered plane irons go. Connected to his shop is a storehouse quite literally stacked-to-the-rafters with mostly white oak blanks for a variety of plane models.

|

The dai-maker’s shop is literally stacked-to-the-rafters with wood blanks. |

Whilte Inomoto prefers white oak, he does turn to red oak for certain plane models. There are thousands of them drying with dates scrawled on their ends in crayon, some as wide as 12-in., from thick planks sawn locally. Also in the storehouse is a custom mortiser that chops out the mouth of the production planes he makes, and barrels of oil for soaking the completed bodies.

Inomoto-san works seated on a thin cushion on a wide and polished wooden stage. Between his legs is his “bench” — the top 2-in. of a post that goes through the floor to a firm foundation below. On the wall behind him are his and his father’s tools, and surrounding him are a few squat but heavy machines on wheels that he moves into place when he needs them, such as when drilling a dai for the steel pin that locks the cap iron and blade in place. His wife helps him, making hot tea on a little wood stove she keeps fired.

He works quickly and deftly, laying out the angled cuts for the mouth, and then with serious force and a large chisel, chopping it out in minutes. Grain orientation of the blank seemed less of an issue than consistent even grain, but the grain is usually quarter-sawn and perpendicular to the sole. Cutting the wedge-shaped grooves for the plane blade, fitting it exactly to a very snug fit, and adjusting the mouth took at most 20 minutes. He then drilled for the retainer pin, fitted the cap iron, and sharpened everything off the platform on a few large waterstones set between his legs. The shavings this plane took were streamers—not curls—flying out behind.

|

More on Japanese Tool Tech |

The blade he fit during my visit had been produced by a famous maker, perhaps taking months to forge and worth a thousand dollars or more. To me it looked no different than any other, maybe just a bit thicker. Inomoto-san pointed out how the high skill of the maker can be seen in the narrow and consistent weld line of the high carbon edge to the wrought back. This unique Japanese metallurgy has always been a mystery to me, how such blades are made and the unique hollows cut into their backs. I was very much looking forward to seeing the process up close.

The Blacksmith’s Shop

Our next stop was a forge very similar in appearance to Inomoto-san’s shop: spare, concrete floor, metal sidewalls, with a few large machines such as trip hammers for production work. The small forge the son worked at sat on the floor, along with an anvil, a sunken tank of water for quenching, and a box of fine sand for slow cooling the steel when annealing. He stood in a sunken manhole with his waist just above the floor.

To light the forge, the son preformed one of the most amazing demonstrations I have ever seen, hammering a piece of bar stock until it glowed red hot. It took all of 20 seconds, whomping the steel on the anvil with machine gun blows, each time turning the bar a quarter turn. The heat came entirely from the friction of moving the steel, tapering it so rapidly and consistently.

|

The payoff for all that handwork is one handsome blade. |

Making a chisel was less dramatic. Contrary to what you read, the softer wrought iron of the body is not old anchor chain (that was used up decades ago), but a piece of bridge girder. The cutting edge was manufactured yellow steel, quality tool steel denoted only by the color of its paper wrapper. It seems another myth, that of blue vs.

white steel and the virtues of one over the other is simply marketing as well; there is little difference.

Once the son had the wrought body and tang of the chisel shaped, he simply forge welded the yellow steel back on. He sprinkled some flux on the red hot body, positioned the equally hot back on top, and hammered them together. He then refined its shape, cut the hollows in the back, hardened, and tempered the tool. Since wrought iron is low carbon, it doesn’t harden as the tool steel cutting edge does, but remains ductile. Its elasticity and ability to absorb shocks, is one of the virtues of this Japanese method of making blades. Nothing magic here, just basic science.

Hollows by Eye

I had always assumed that the consistent hollows on the back of a Japanese blade were done with a precision grinder of some kind. Hardly. The father just held the back to a very large grindstone and worked by eye. He also demonstrated scraping the hollows using considerable pressure with a spokeshave-like scraper with a narrow curved blade.

Souvenir Tools?

The last stop was at the shop of Hirade, a dealer of the best woodworking tools in Japan. Even though it was tiny, there were dozens of different planes, chisels, natural sharpening stones, marking tools, and everything a craftsmen could need. My enthusiasm was dampened only by imagining carrying in my already full pack, anything more.

Comments

"My enthusiasm was dampened only by imagining carrying in my already full pack anything more."

Garret, would it have been possible to have some select tools shipped home? ;-) Of course after paying, I imagine your wallet would have been so light, you would be in danger of defying gravity!

So, after reading your article, it makes me wonder why some of the Japanese chisels I see for sale have "Damascus" like steel, which I've heard is two layers of soft and hard steel folded and pounded multiple times to layer the steel like the old samurai swords. I’ve also heard that this does not add any functional benefit beyond the first two layers, but personally I wouldn’t know. The grain like pattern does look nice though.

Very interesting, but I can assure you that there are significant differences among the various alloys that are all called steel, differences as large as those among various species of wood. Unlike wood, different steels look pretty much the same,but like wood they have different properties that make them more or less suitable for various uses. It's far from "just marketing."

Small differences in the carbon content and the addition and amounts other metals such as phophorus, sulfur, vanadium, cobalt, chrome, and so on, are responsible for these differences.

It's true, however, that the differences are less important for making woodworking edge tools than for some other applications, because cutting wood is a relatively undemanding task for a steel tools. Woodworkers do prefer to have tools that can take and hold a keen edge and have decent shock resistance; the ability to retain their shape when very hot is of less importance. Pretty much any high-carbon steel can be used to make a satisfactory woodworking tool, although some alloys are better than others, and there are trade-offs. Wear resistance, for example, comes at the price of difficulty in forming a truly sharp edge, for technical metallurgical reasons I won't go into.

In this country it's customary to mark the ends of bars of tool steel with different colors of paint to denote the nature of the alloy the bar is composed of. In my shop I have pieces marked with yellow paint, blue paint, red paint, and white paint, which I suppose is the origin of the terms "white steel," "blue steel" etc.

It's usually impossible to know what kind of steel was used in the manufacture of production woodworking tools, but some makers do specify it in their sales literature. To someone who is acquainted with steels and their properties, this conveys important information. Those who aren't so acquainted are naturally confused by it and prone to conclude that it's "just marketing."

There's a difference between a piece of furniture made of rosewood and one made of poplar, and there's a difference between a tool made of high-carbon steel and one made of chrome-vanadium steel (not a very good choice for a woodworking edge tool). If you buy high-quality tools from a good maker, you probably needn't concern yourself much with what kind of steel was used unless the subject interests you particularly, but it's a mistake to think that it makes no difference at all.

I'd be interested to know the name of the father/son team who were kind enough to show their chisel making techniques. It was a very interesting article. Thank you for sharing this information with us all.

One question though, aren't there makers who still offer chisels made with the old anchor/anchor chain material? I thought I'd read on a reputable Japanese seller's site that this old material was made without a common current chemical (sulfur is what comes to mind), which provided a beneficial aspect compared to the current wrought iron.

Look forward to your thoughts. Cheers.

Lee

Have any video footage been taken? I am sure its not just me that would love to see some of those intriguing descriptions come to life, of sorts.

Thanks for a most enjoyable sharing of experience and may you have many more!

Japanese Planes - the pin across the body (dai) retains ONLY the chip-breaker! The blade is held in place by the taper in its thickness, which is the reason for the somewhat lengthy process of setting up a new Japanese plane. Anyone who has a copy of Toshio Odate's book Japanese Woodworking Tools can read about this on pages 89-91. For those who do not, a new printing of the paperback version has been promised by the end of the year (and there are a few copies available from booksellers who list with Amazon). Alternatively, buy the 2-DVD set by Jay van Arsdale on Japanese planes.

Japanese Chisels - a review of the ones from Grizzly seems to list the need for mushrooming the end of the handle to retain the ring as a negative; actually it's required for all Japanese chisels - find that in Odate's book also, p. 63.

StuinTokyo went with Garrett on this trip. He may have additional video from the visit. He may also be able to get additional details on these tool makers. Stay tuned. -Gina, FineWoodworking.com

Great story but I'm hung up on one item.

Heating a piece of bar stock to red-hot by hammering by hand in 20 seconds sounds superhuman. It's hard to imagine steel being heated like this under ambient conditions even by hammering with machine power. I wish there was more explanation.

Sorry for taking so long to notice this thread!

The blacksmith in the pics is Tasai, I'm fairly sure, I have to check my notes. I do have video, at the time, my computer was dying, so I did not process much video, but we now have a new Mac, so I'll get some done. I do have video of Tasai Junior lighting the forge, amazing!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in